Make Stories Succeed With This One Weird Trick

One âweirdâ trick can help anyone who wants to share or craft great stories.

Here I could promise instant results. I could pretend Iâve mastered this One Weird Trick, or sort-of imply I have this hidden backstory that makes me qualified. But then you would learn the truth, and I would have clearly shown I donât have a clue how the trick works.

Some Christian authors have mastered the One Weird Trick. Among these are the authors commonly cited as examples of Christian-written fantastical fiction that has met with wider success: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, of course, but also Frank Peretti, Ted Dekker, and increasingly, Andrew Peterson. Each of these authors managed to follow the One Weird Trickâand thatâs why they succeed, while other stories, even good ones, still languish.

Hereâs the one weird trick to making stories succeed:

Gain trust.

Thatâs it.

Christian storytellers: gaining trust

For a while Iâve pondered this simple and pure truth, but more so thanks to the discussion after Why Isnât There More Christian Fantasy? Readers of that article raised the successful names I mentioned above. So I recalled why theyâve âbroken outââthat is, for Christians:

- C. S. Lewis did not first succeed thanks to âThe Chronicles of Narnia.â First he gained trust with his long career as a professor of languages and medieval literature. Then he built acclaim among Christians thanks to his broadcast talks on BBC Radio and his nonfiction books on biblical themesâexplicitly Christian material, by the way.

- J. R. R. Tolkien was already a professor of languages. His novels succeeded among Christians thanks in part to his proximity to Lewis, who gained Christiansâ trust.

- Frank Perettiâs This Present Darkness met moderate success until musician Amy Grantâs team began promoting it. Suddenly the angels-versus-demons spiritual warfare novels began flying off the shelves. Grantâs team helped arrange for Peretti to write a sequel. But after that hoopla, Peretti tried other kinds of stories.1

-

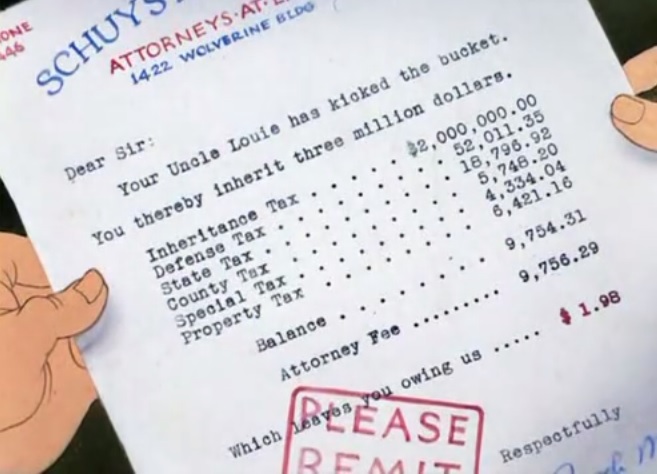

Blessed Child by Ted Dekker and Bill Bright: before and after.

Ted Dekker began writing with Campus Crusade for Christ founder Bill Bright, a name known to evangelicals. Only then did Dekker write his own novels. (Compare the earlier cover for Blessed Child versus the new cover. Whose name got bigger?)

- Andrew Peterson began his career as a folk musician. Christians may struggle with music, but we trust music more than fiction. Long before I heard of The Wingfeather Saga, I had heard of Petersonâs music. He is popular among mainstream evangelicals, butâhereâs a secret for youâheâs especially popular among a Christian segment often called the âyoung, restless, Reformedâ set. Thatâs a great base in which to gain trust with fans. Oh yeah, Andrew Peterson! I donât read fantasy, but Iâm sure this book is fine, biblical, and excellently made, so long as itâs him. Must be great for my kids too.

The simple gain trust principle is even behind the oft-pommeled tendency of filmmakers and studios to return to remakes and reboots2 of already-known films. Behind âbrand recognitionâ is this simple fact: Brand recognition is often the same as brand trust, or else, the effect is the sameâfolks buy tickets.

In fact, this can work out negatively: I âtrustâ those Transformers movies to be what they are, every time, based on what Iâve heard, despite never seeing a single one (and not wanting to). In a way I respect director Michael Bay for that reason. He gained trust.

âJustice Leagueâ filmmakers: gaining trust

Justice League: Dawn of Logos

Another director has struggled to gain the same trust: Zack Snyder, of Man of Steel and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice fame. For my part, Snyder does have my trust thanks to his amazing work in both those films. (Iâve not seen his other films.) But other fans feel differently. Thatâs why several fandom-news writers were invited last week to the set of the followup DC Extended Universe film, Justice League, with no conditions on what they wrote.

Warner Bros. and Snyderâs team clearly know that, rightly or wrongly, they must gain more trust with fans. Batman v Superman may not have been to everyoneâs taste. But itâs taken me a while to see the filmâs critical thrashing was due to many other mistrust factors, like:

- People still expect Superman to behave like a shallow, flat cartoon, not a real person.

- People still expect Superman to be locked into their idealization of âChristopher Reeve,â e.g. not the Christopher Reeve of all four Superman films, including the abysmal III and IV, but the âChristopher Reeveâ or popular memory. (A similar popular memory insists Sherlock Holmes must always be saying, âElementary.â)

- People just got finished with Christian Bale as Batman in The Dark Knight trilogy, and were grumpy (or felt they should be grumpy) about a rebooted Batman story.

- Ben Affleckâs casting as Batman rankled fans who felt it was time for a piling-on, due in part to Affleckâs infamous attempt as the titular hero of Daredevil (2003).

- Popular and simplistic expectations of superheroes still cause people to ask what that one woman at Taco Bell once asked me: âWhy are Batman and Superman fighting? Theyâre both good guys!â So they doubted the filmâs very premise.

- Many people had not even cared to see Man of Steel (2013) before they saw Batman v Superman. Thatâs like seeing Empire Strikes Back before seeing Star Wars.

- Snyder personally catches absurd levels of ire because of his previous movies.

-

My suggestion for the upcoming Green Lantern Corps film: Keep all of the cosmic predestination themes from Green Lantern (2011). But move the entire story to outer space.

DC gets ire thanks to âokayâ films like Green Lantern or horrid ones like Catwoman.

- A growing popular line (especially among the âintelligentsiaâ) is that we have a âglutâ of superhero movies that really, come on now, must be ended eventually, because grown-ups have more important things to do, like social justice. Batman v Superman ended up a âscapegoatâ thanks to its groundswell of critical thrashing.

- And of course, some critical thrashing was simply a trend. One popular personâwho has gained trust in media circlesâthrashes it, then another thrashes it, and then it suddenly becomes cool. (A similar effect occurs in real-life mobs.)

- ⌠Which leads to bad word of mouth about the film, because now the person on the street has been led to believe âeveryone saysâ Batman v Superman is a real stinker.

With all these factors of mistrust at play, Iâm stunned the film did so well as it did. Nearly all my friends loved it. And the franchise has only jolted a bit on the tracks; it has not derailed.

Still, the filmmakersâ attempts to reach out to fans and critics should help them gain trust.

Gain trust

Gain trust

Once more, I donât promise any formulas. Iâm only showing observations. They may seem blatantly, dully obvious to some of you, and a glowing insight to others, like it was to me.

How can fans and authors of Christian fantastical stories follow this gain trust principle?

How could this simple idea help these stories get better and find more readersâboth among Christians and among broader audiences who need the kinds of stories we offer?

I have my ideas. But perhaps for now Iâll keep them to myself. First Iâd rather hear yours.

- This present (and future) Peretti, Gene Edward Veith, Oct. 25, 1997, World ↩

- âRebootsâ are not the same as remakes. ↩

Why are we asking this question? Does anybody else? Are there agnostics or Hindus batting definitions of agnostic or Hindu fiction back and forth? Were Christians trying to define Christian novels a hundred years ago, or were novels just novels then?

Why are we asking this question? Does anybody else? Are there agnostics or Hindus batting definitions of agnostic or Hindu fiction back and forth? Were Christians trying to define Christian novels a hundred years ago, or were novels just novels then? I wonder if they are all driven, in part, by the ever-widening gulf that we, as Christians, experience between our religion and our culture. Gone is the easy talk of Christian civilization, and Christian nations, and (the phrase makes one shudder) a Christian race. I would not oversimplify the past, or our ancestors. History is always messier and more complex in the making than it appears when we look back on it finished. Yet I think it true that in older days, the Christian religion was often taken as part and parcel with western civilization, like Shakespeare and the common law and scientific advancements.

I wonder if they are all driven, in part, by the ever-widening gulf that we, as Christians, experience between our religion and our culture. Gone is the easy talk of Christian civilization, and Christian nations, and (the phrase makes one shudder) a Christian race. I would not oversimplify the past, or our ancestors. History is always messier and more complex in the making than it appears when we look back on it finished. Yet I think it true that in older days, the Christian religion was often taken as part and parcel with western civilization, like Shakespeare and the common law and scientific advancements.

From my first involvement in writing and publishing, I’ve been confronted with the question, overtly or by suggestion, what is Christian about this novel? Ten years ago Christian fiction was know for conversion scenes. As in, a character who was not a Christian came to faith in Christ. The end.

From my first involvement in writing and publishing, I’ve been confronted with the question, overtly or by suggestion, what is Christian about this novel? Ten years ago Christian fiction was know for conversion scenes. As in, a character who was not a Christian came to faith in Christ. The end.  In other words, I was thinking about the possibility that Christian speculative writers were not doing justice to our individual experiences. Instead, we were writing to a template, to what we thought a person had to believe in order to be a Christian. So if someone was to convert, we had to satisfy all the important requirements. There really weren’t stories about thieves on the cross converting moments before they died. Or corrupt government agents promising to make amends with those they cheated and to proceed honestly from this point on. Or prostitutes showing their repentance by lavishing expensive perfume on the One who had forgiven them. Or paralyzed men jumping up and carrying their pallets as they leaped and praised God. Or men freed from demons, sitting clothed, in their right minds, and begging Jesus to join his followers.

In other words, I was thinking about the possibility that Christian speculative writers were not doing justice to our individual experiences. Instead, we were writing to a template, to what we thought a person had to believe in order to be a Christian. So if someone was to convert, we had to satisfy all the important requirements. There really weren’t stories about thieves on the cross converting moments before they died. Or corrupt government agents promising to make amends with those they cheated and to proceed honestly from this point on. Or prostitutes showing their repentance by lavishing expensive perfume on the One who had forgiven them. Or paralyzed men jumping up and carrying their pallets as they leaped and praised God. Or men freed from demons, sitting clothed, in their right minds, and begging Jesus to join his followers.

Studios introduced audiences to Marlin, a clownfish father who is overprotective of his son, Nemo. But when Nemo is kidnapped, Marlin must struggle to put aside his fears and find his son. Tomorrowâs sequel Finding Dory promises similar themes.

Studios introduced audiences to Marlin, a clownfish father who is overprotective of his son, Nemo. But when Nemo is kidnapped, Marlin must struggle to put aside his fears and find his son. Tomorrowâs sequel Finding Dory promises similar themes.

Iâve heard of a new video game called âOverwatch.â Iâve read a few reviews of this game. Some focus on the differing roles of game characters, each of whom has different gifts and abilities to use in battle against enemy hordes. Immediately I thought of the apostle Paulâs description of the different members of the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12.

Iâve heard of a new video game called âOverwatch.â Iâve read a few reviews of this game. Some focus on the differing roles of game characters, each of whom has different gifts and abilities to use in battle against enemy hordes. Immediately I thought of the apostle Paulâs description of the different members of the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12. Another famous character could wield the âsword of the Spiritâ found in Ephesians 6:17. Iâm speaking of Rey from Star Wars: The Force Awakens and the upcoming new Star Wars films. In the first story, Rey gains a lightsaber, a very famous weapon that reminds us of the apostle Paulâs description of a sword that is âthe word of God.â

Another famous character could wield the âsword of the Spiritâ found in Ephesians 6:17. Iâm speaking of Rey from Star Wars: The Force Awakens and the upcoming new Star Wars films. In the first story, Rey gains a lightsaber, a very famous weapon that reminds us of the apostle Paulâs description of a sword that is âthe word of God.â Duane Johnson calls himself The Rock.

Duane Johnson calls himself The Rock. I donât regularly watch âSupernatural.â In fact, I havenât seen a single episode. But Iâve seen enough commercials for it while watching other shows. And I know there are two brothers, and one of them is named Dean Winchester, and one or the other says, âWeâre on a roll.â

I donât regularly watch âSupernatural.â In fact, I havenât seen a single episode. But Iâve seen enough commercials for it while watching other shows. And I know there are two brothers, and one of them is named Dean Winchester, and one or the other says, âWeâre on a roll.â

Instead, society demands a relativistic frame of mind. Truth has become subjective, based on personal feelings, preferences, and opinions. This is dangerous when it comes to telling stories in any medium.

Instead, society demands a relativistic frame of mind. Truth has become subjective, based on personal feelings, preferences, and opinions. This is dangerous when it comes to telling stories in any medium. In Mockingjay, weâre left with an empty feeling bordering on despair (kudos to the movie for an ending that contained a glimmer of hope).

In Mockingjay, weâre left with an empty feeling bordering on despair (kudos to the movie for an ending that contained a glimmer of hope).

2. So we can Send A Message.

2. So we can Send A Message.