In this, the last of my posts on the now-complete Auralia Thread, I have the privilege of interviewing author Jeffrey Overstreet. With no further ado …

Rachel: Before we even start, let me say thank you for an extraordinary reading experience. In The Ale Boyâs Feast especially, I found myself reading a story that not only enveloped me in its world and characters, but caused me to look at my own life differently. Iâve been challenged to pay more attention to the beauty that surrounds me and think about the realities it might be pointing toâand to stay faithful to the dreams God has given me, knowing that ultimately they will lead me to Him. That might not even be exactly what you were trying to say, but I appreciate the message!

Jeffrey: Thank you so much, Rachel. I wanted to tell the best story I could, given the time and resources available to me.

I knew that my job was to pay attention to the characters, their decisions, the consequences of those decisions, and the textures of the world in which all of this took place. As for any âmessages,â well⊠I wasnât going to worry about that. I believe that a storyteller should focus on bringing the story to life, and messages will emerge on their own. If the storyteller stops and concerns himself with delivering messages, than the storytelling suffers and becomes heavy-handed.

So Iâm delighted to hear that the story meant something to you. I learned a lot from following these characters around, and if readers learn lessons of their own, thatâs an extra blessing.

Rachel: The Auralia Threadâs most obvious theme is art, and the power of art to call us beyond ourselves. But it certainly isnât the only theme. What other themes were in your head when you began, and what themes have arisen in the writing process? Have any surprised you?

Jeffrey: It all started with the question, âWhy do most people reach an age where they fold up their imaginations and put them in a closet? Why do most people decide that make-believe is just for kids?â

But later, that led to questions about what leads people to lose their curiosity about the truth, and to set up camp in a particular church denomination or a particular political party or a particular academic discipline and to toss away the lenses that might help them see the truth more fully.

I think that almost any theme I could highlight would be a theme that surprised me. I didnât go into the story to explore themes. I went into the story because a question inspired a picture in my mindâan intriguing picture of a society that made imagination illegal. I wanted to step through that picture frame, explore that society, and get to know the broken-hearted character who was so grieved by it.

As a result, pretty much all of what transpired surprised me. I didnât start with an agenda to fulfill or a lesson I wanted to deliver. I was curious about characters whose stories are still teaching me lessons.

Rachel: Speaking of surprises, what other aspects of the series have surprised you?

Jeffrey: Many of the relationships of the characters changed considerably over the course of the series in ways that really surprised me.

For example, I never anticipated that Tabor Jan would become conflicted, his affections divided between two women.

I didnât anticipate that the two old thieves, Krawg and Warney, would become separated and have two separate but world-changing adventures.

Nor did I anticipate that Krawg would become a storyteller, or that his stories would become prophetic. Those developments began as simple cases of âWhat if?â Then they picked up speed and took me to some exciting places that were not part of the original outline.

There are some big surprises in the epilogue of The Ale Boyâs Feast that were not part of the original plan either, but when those possibilities presented themselves, I was thrilled. It felt like opening Christmas gifts that are absolutely perfect, and you canât believe that you didnât guess what was in those packages ahead of time. But I canât talk about those surprises.

I also didnât know, until I got to the fourth book, if the mystery of the ale boyâs real name would ever be solved, or what would ultimately happen to King Cal-raven. I entertained all kinds of possibilities. Then, one day, I suddenly knew what to do about both of them. I still donât know how the ideas came to me. It felt like sitting on the beach, hoping to see whales come to the surface, when youâre not even sure if whales swim in this part of the world. You wait and wait for months and months, and then suddenly, there they are!

Rachel: One theme I have noticed and appreciated more as Iâve read and reread the books is that of the meanings we impose on what we see around usâas Scharr ben Fray says, the stories we choose. Some hit on the truth, and it leads them home. OthersâRyllion, the mages of House Jenta, the Defenders of Auralia, even Cal-Raven for a timeâhit on falsehood, and their own false meanings have the power to destroy them. Youâve done a powerful job of showing, through various characters and cultures, that what we believe has powerful consequences in our lives.

Jeffrey: Thanks, Rachel.

This is a good example of how storytelling can lead you into unexpected places. I never intended to explore themes like those you describe, but these characters took me there anyway.

When I wrote Auraliaâs Colors, Scharr ben Fray seemed likely to become one of those typical fantasy wizardsâlike Gandalf or Obi-Wan Kenobi. But the more I encountered him, the more strange and suspicious he seemed to me. I could sense that he wasnât going to fit the mold of the All-Knowing Guide. In the closing chapters of The Ale Boyâs Feast, when we learn what heâs really about, well⊠he ends up being quite different than anything Iâd anticipated.

Cal-raven faces a difficult choice near the end of this series. Should he abandon the summons that he heard as a child, which he thought was coming from The Keeper? Or should he go on answering that call, even though the truth of its origin is more mysterious than he thought?

As I wrote about his struggle, I realized that this was, in some ways, the story of my own life. So many ideas that I had in childhood about right and wrong, good and evil, imagination, and God evolved considerably when I was in high school, and they evolved even more when I was in college.

As we grow up, we throw out clothes weâve outgrown, or we give them to younger people, and we going shopping for new clothes that fit. Then, we do it again. Itâs that way with our vocabularies for so many mysterious things. In Ravenâs Ladder, Cal-raven thinks he has the world all figured out. Then he sees something that bursts the seams of his ideas. So heâs caught between two possible responsesâhe can despair, or he can open himself to a bigger idea, one that heâll have to struggle to âput on.â

Weâre all trying to fit the truth into our heads and our hearts. But our heads and our hearts are cracked. We can only catch pieces of the truth here and there. Those cracks and imperfections should keep us humble. We have to assume that our current understanding is probably insufficient.

Now, donât get me wrongâIâm not saying thereâs no real, absolute Truth. But when we treat Truth as something we can obtain, own, and manipulate for our own benefit, weâve missed the point, and we start to lose what little wisdom weâve gained. The truth isnât a list of the âright answersâ; itâs not a puzzle we can solve or a property we can purchase. Itâs a living entity, inviting us into a relationship. If we apply ourselves to the daily discipline of loving it, we can enjoy its rewards. But when we decide that weâve âgot it,â and that weâve become an authority on it, weâve lost it.

In that sense, the Truth is more like a magazine than a book. Itâs a subscription that never runs out, so long as youâre willing to keep reading. Thereâs always more.

Rachel: Your writing style has a poetic denseness to it thatâs really rewarding to dig intoâbut also makes speed reading an exercise in futility. Thatâs one of the most rewarding things about the books, in my opinion. They have to be read slowly and thought through and savoured. But obviously, not everyone reads that wayâand Iâve noticed some pretty blazing misunderstandings being showcased in Amazon reviews! Have you found any of these particularly frustratingâor amusing?

Jeffrey: Iâm disappointed when I see that the primary audience I had in mind as I wrote The Auralia Thread has yet to discover the books.

Mostly, the books have been read by people who read only Christian Fiction. And thatâs a shame, because my books arenât Christian fiction. Theyâre fairy tales, fantasy novels, meant for everybody. I didnât write a religious allegory, and when readers use only a Religious Allegory lens when they examine the book, theyâre missing a lot.

Only a few reviewers like yourself have looked closely enough to recognize some of the main themes I discovered as I wrote the stories. But thereâs nothing I can do about that.

Some reviewers were upset when they encountered characters who were fools or criminals. That makes me ask, âWhat kind of books do they like to read?â My world is full of fools and criminals, and Iâm one of them. So Iâm interested in stories about people like that. And I grew up reading The Bible, in which even the heroes of the faith are adulterers, murderers, liars, drunkards, thieves, and worse.

Iâm amused when I read that some readers thought that character names like âScharr ben Frayâ were too difficult. They must not read much fantasy. They should stay away from Star Wars, where theyâll have to deal with a guy named âObi-Wan Kenobi.â And most who claim that The Ale Boyâs Feast confused them will also tell you that they didnât read the first three books in the series. If I skipped The Hobbit, The Fellowship of the Ring, and The Two Towers, and started reading The Return of the King, Iâd be confused too. That wouldnât be Tolkienâs fault.

Iâm glad, Rachel, that you enjoyed the challenge of The Auralia Thread.

Books that can be ready speedily are like milkshakes. Milkshakes taste good, but they donât require any effort, and they donât provide a lot of nourishment. You probably arenât still thinking about a milkshake the day after you drink it.

The books that have meant the most to me are feasts that I canât stop thinking about, feasts I want to go back and experience again. They made me do the hard work of reading closely, thinking them over, re-reading them, sharing them, and discussing them.

And my favorite books are about more than just âwhat happens next.â Theyâre memorable for their form as well as their content. They have a music in their language, and their characters and events are interconnected in ways that only become evident to the most observant readers. I want to learn to write like that.

So as I wrote The Auralia Thread, I tried to be attentive to details in a way that would slow readers down and give them an experience for their whole imagination. I want storytelling to be like deep sea diving, not splashing around in the shallows. You might find some loose change in the shallows, but you might find a buried treasure chest in the deepâand not only that, but youâll be stronger for having to swim so far below the surface.

Rachel: Youâve accomplished something really wonderful with this series, but I know itâs sometimes been frustrating to work under publication deadlines and constraints. Looking now at your finished work, do you have any regrets?

Jeffrey: Well, the deadlines were very motivating. I wonât complain about them, because I agreed to them. And the whole publishing endeavor came as an unexpected blessing, so even though I had to rush to the finish line, Iâm just grateful I got to participate in the race at all.

Having said that, though, The Auralia Thread is a case of âWhat I Could Manage.â Eight months is a very short amount of time in which to write a novel, especially when youâre working a full-time job. I donât have regrets, but I did learn a lot about my own writing process, and what I need in order to achieve something that feels finished.

Iâm determined to write my next novel before I sign any contracts. I want to give future stories more time to mature before I hand them over.

Rachel: And finally, the classic interview questionâwhatâs next for you?

There are a lot of characters living in my head. Many of them havenât been introduced to an audience yet.

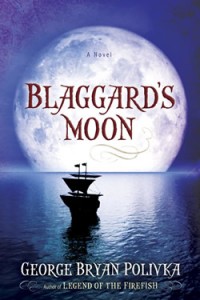

My favorite character lives in a very different world from Auralia and the ale boy. I think itâs time for his story to get a fresh coat of paint, and then Iâll see if a publisher would be interested in delivering him to an audience. That would launch a whole new seriesâsomething much more whimsical and action-driven than The Auralia Thread.

I also have two other books, quite different from anything Iâve done before.

One is a non-fiction project about the power, possibilities, and dangers of unstructured time. It would be like a work of archaeology, where the site of the dig is Childhood, and the treasures are stories and ideas weâve forgotten as weâve grown up.

The other book is about some historical figures who Iâve never seen as the lead characters of a fantasy novel before, and I feel compelled to write that book before somebody else does.

But for a little while, Iâm just going to rest, spend some time with Anne, and spread the word about her first book of poetry, Delicate Machinery Suspended, which is being published this summer. I want to read a stack of books, see a bunch of movies, clean up the piles of debris from the last five books that are stacked around my study, and rediscover the joys of writing with no deadlines and no agenda.

My definition of poor fiction âpreachinessâ: inauthentic and hollow (even if true) spiritual content that has little to do with its actual story. (But should we correct bad âpreachyâ fiction only with even more preaching about how bad that is? The Gospel targets the deeper issues.)

My definition of poor fiction âpreachinessâ: inauthentic and hollow (even if true) spiritual content that has little to do with its actual story. (But should we correct bad âpreachyâ fiction only with even more preaching about how bad that is? The Gospel targets the deeper issues.)

As with the previous common criticisms, Iâve often uttered this one myself. Iâve read some Christian books that I would call preachy, and not in a good way. Yes, some Christians seem to think a writing ministry is only God-honoring if they include the whole Gospel call in the novel someplace â regardless of whether the story is based on direct redemption themes.

As with the previous common criticisms, Iâve often uttered this one myself. Iâve read some Christian books that I would call preachy, and not in a good way. Yes, some Christians seem to think a writing ministry is only God-honoring if they include the whole Gospel call in the novel someplace â regardless of whether the story is based on direct redemption themes.

Iâve read Christian novels that were wrongly preachy. But Iâve also read novels that werenât nearly preachy enough, which made me wonder what the heck was spiritually going on. Nothing about those novels could honestly be called Christian apart from sporadic prayers, references to God or morality or going to church, Â or maybe exhortations to Have Faith.

Iâve read Christian novels that were wrongly preachy. But Iâve also read novels that werenât nearly preachy enough, which made me wonder what the heck was spiritually going on. Nothing about those novels could honestly be called Christian apart from sporadic prayers, references to God or morality or going to church, Â or maybe exhortations to Have Faith.