Beyond Story Battles 1: Living For The Fight?

Pick a protest, any protest. Right now we have at least two popular ones from which to choose: the âTea Party,â for political conservatives, and the âOccupy [Whatever],â for the other guys. Must be a pack of fun. You get to run around and yell, do some rage, react, or even (depending on who you listen to) be a deep dark hidden evil sick racist, or Marxist.

Pick a protest, any protest. Right now we have at least two popular ones from which to choose: the âTea Party,â for political conservatives, and the âOccupy [Whatever],â for the other guys. Must be a pack of fun. You get to run around and yell, do some rage, react, or even (depending on who you listen to) be a deep dark hidden evil sick racist, or Marxist.

But for a term like protestors, has anyone noticed that a lot of their rhetoric is actually anti? Anti-this. Anti-that. Reaction-based response. Much less in support of anything.

I donât mean I have some expectation that protestors should offer detailed alternatives or else shut up. Even general pro-something-ism isnât common. Who walks up to most protestors, asks why theyâre there, and hears: âOh, Iâm just thrilled to be with people like me; I think that if we all get together, we can do great things! Hm, and I guess that also includes opposing our enemies.â More likely you instead hear first about the Enemies. How evil they are. How they even eat babies. And kittens. And baby kittens.

Sure, some of those enemies are rotten. (I donât mean to imply Iâm completely Neutral here.) But is that any personâs destiny, both in an eternal sense and a temporal sense? To fight, fight more, wage ideological war, sometimes break things â Anti, Anti, Anti?

âThey fight, and bite âŚâ

Iâm reminded of Megamind, the giant-blue-headed genius in the 2010 movie of the same name. He spends his life fighting Metro Man, a Superman-like hero, based mainly on the fact that every hero needs a villain. But secretly Megamind actually admires the hero. That is revealed when Megamind, wildly and accidentally deviating from the usual script, actually wins, defeats Metro Man, and finds that heâs taken over the city â then has no idea what to do with himself. He lived only for the fight, not actually winning it.

Iâm reminded of Megamind, the giant-blue-headed genius in the 2010 movie of the same name. He spends his life fighting Metro Man, a Superman-like hero, based mainly on the fact that every hero needs a villain. But secretly Megamind actually admires the hero. That is revealed when Megamind, wildly and accidentally deviating from the usual script, actually wins, defeats Metro Man, and finds that heâs taken over the city â then has no idea what to do with himself. He lived only for the fight, not actually winning it.

Iâm also reminded of some rhetoric â not all! â that I see in Christianity, and to bring things closer to home, even some rhetoric about Christian visionary stories and novels.

Beckyâs column last Monday reminded me of a recent example. She quoted freelance writer Tony Woodliefâs criticism of Bad Christian Art. Starting with a secular criticâs question (I canât help but ask: how come anyone buys unqualified stock shares in them anyway?) Woodlief had faulted Christian fiction, and Christian movies in particular, for offering cheap plot resolutions, characters, and sentimentalities.

Some of what he said is very agreeable: for example, that âbad art derives, like bad literary theory, from bad theology.â Absolutely. Bad anything derives from our bad theology. Moreover, consistently applying that bad theology makes things even worse.

Yet Iâd point out that this is the point: our beliefs should start with theology â theology proper, meaning âstudy of God.â They donât start with Study of Sin. Or Enemies. Or Antis.

Meaning: our ultimate goal in Life, the Universe, and Everything, is not: We Must Fight.

If we do make the battle-centered life our goal, even subconsciously, without reminding ourselves why we hope to end the fight, one or more of these symptoms may plague us:

1. Weâll be nearly unbearable jerks. In churches, politics, organizations, families, and creative circles â including fiction â it will be clear that all we want to do is fight the Bad Guys. Not only do we fail to have love or respect for them at least as noble opponents (as Megamind truly thought of Metro Man), we have no vision for what, exactly, would happen after even good fights are won.

2. Weâll automatically act as though our chief end is to avoid Bad Things forever. God, instead of being our chief end, the One we proactively desire to glorify and enjoy forever, is turned into a means to other ends. Hijacking Him for goodness-based battles is just as bad as hijacking Him for evil choices.

3. Our stories will stink. I sincerely believe a lot of Christian-fiction criticism could be resolved, not by harping constantly on how our stories arenât Gritty or Realistic enough, but by putting both showing-real-evil and the happy ending into Biblical perspective.

As I noted last Monday, those who claim to expect all Christian art to include the full Gospel, with âtotal depravityâ and all, donât apply this to the Bible itself. They couldnât. If they did, every Psalm would be required to undergo a Gritty Rebootâ˘, to ensure none of them sang exclusively about how great God is and how His wondrous creation praises Him, without also including Realistic Evil. Why try to be more spiritual than God?

4. Worship and rest will make no sense. Yes, âprosperity gospelâ and saccharine faith notions are far too common. Christians must oppose them. The real Gospel is better.

But some, seeing a need to fix only those problems, are overcorrecting with implications or statements that all Christians should ever do is prepare for suffering. Or we bemoan our present lack of suffering (why donât I suffer as much as Persecuted Believer X in another nation?). Or we base our beliefs and actions on goals of being only Gospel carriers â as if fulfilling the Great Commission and teaching all that Christ commanded us (that is, all of the Bible!) includes only the tell-others-to-repent-and-believe parts.

Rather, all of Christâs commandments include the truth that sometimes He gives us rest. Sometimes He gives us material blessings. And He commands us not just to distribute the Gospel and try to sign up other distributers, multilevel-marketing-style, but to worship Him and enjoy Him even now, through all that we do, even before He returns.

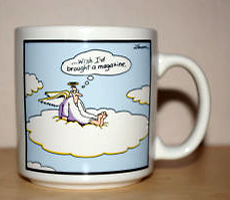

5. In theory, everlasting life would be boring. Iâve asked this question before. When I used to waste more time either with cultural-only âfundamentalistâ Christians, or else liberal âemergentâ Christians, Iâd phrase it this way: âImagine what would happen if, in all your zeal to Fight the Good Fight and thatâs it, you die and end up in Heaven. There, you would find nothing to fight. No poor people to feed. No heresy to condemn. Nothing that makes you feel or act like a Warrior as an end to itself. All youâd have left to do is worship Christ in other ways, be it music or work, exploration, artistry, learning and more. In such a place, when all our vestiges of self-as-savior are gone and there is only one Savior of us all, are you sure you would not be bored?â

5. In theory, everlasting life would be boring. Iâve asked this question before. When I used to waste more time either with cultural-only âfundamentalistâ Christians, or else liberal âemergentâ Christians, Iâd phrase it this way: âImagine what would happen if, in all your zeal to Fight the Good Fight and thatâs it, you die and end up in Heaven. There, you would find nothing to fight. No poor people to feed. No heresy to condemn. Nothing that makes you feel or act like a Warrior as an end to itself. All youâd have left to do is worship Christ in other ways, be it music or work, exploration, artistry, learning and more. In such a place, when all our vestiges of self-as-savior are gone and there is only one Savior of us all, are you sure you would not be bored?â

Naturally, I have to ask that question of myself. I wonder if my own habits and even writing style give that impression. This is likely why Iâm drawn back to fiction. Unlike a steady diet of, say, doctrinal or apologetics materials, fiction helps with the humility. I canât just use a story for spare parts for my own Battles. Iâm instead confronted with a world, with people, making completely different choices. Itâs not my story; itâs theirs.

And that implicitly, or explicitly, reminds me that life isnât my story; itâs His. My mission is not only to win against the bad guys â even the really irritating ones who deny Hell or claim we must support only shallow stories â but to delight, proactively, in Him.

Visionary stories, then, are not merely a means of Battling against Christian novels with shallow themes, or without cusswords, violence, or dungeons and dragons. They are a means of worship â or, I suggest, they should be. True worship doesnât get salvaged for parts to build the latest Christian-industrial-complex weapon. (I must keep reminding myself of that!) Instead, worship is a means only to God, to enjoying Him personally.

So, those could be a bunch of antis of my own. We shouldnât fight for fighting alone; in fact, we should fight against the inclination to fight all the time with no victory in sight. By itself, thatâs completely self-refuting. It needs emphasis on the pro-reasons why we fight any battles, or enjoy visionary fiction, or do anything. However, Iâll save the pro-reasons for the near-future Beyond story battles 2: anticipating the After-world.

Thus, when the series is done, both will be best read together, just as one should take into account all of Godâs big Story, and our smaller ones. Sure, we shouldnât skip over the battles and our need to fight them. But we also should not confuse those temporary means for the everlasting Chief End.