Lord Of The Fantasies: Beholding Middle-earth

Though it seems odd to me now, both math and a ten-year-old calendar prove I must have read The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, for the first time, in ten days.

Though it seems odd to me now, both math and a ten-year-old calendar prove I must have read The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, for the first time, in ten days.

As you may have previously read, I am slightly ashamed to admit my introduction to the mythical universe of J.R.R. Tolkien came very late in life. I did not read The Lord of the Rings until the first film of Peter Jacksonâs trilogy had already released.

Only one point in my favor, perhaps: I did finish the first book, before I saw the film.

Now Iâm trying to recall my memories, more than ten years later.

You might also recall your Middle-earth memories. When did you first read the books, and/or see the films? On what type of screen did you first see the films, anyway? How also did you react to the extended versions of the films, on the Special Edition DVDs?

âThe Fellowshipâ of the book

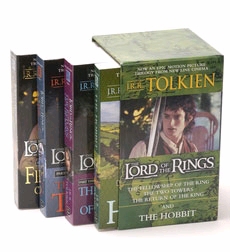

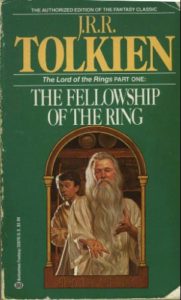

On Christmas Day, 2001, I received a paperback set of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Book fans, you may fire your Elven arrows now, for this set was a Movie Tie-In Edition. Frodo with his sword Sting was on the front of Fellowship. On the front of The Two Towers was Saruman; on its back, I think, was a woman with blond hair, whom I learned didnât even appear in the first book (this, I later found, was Ăowyn). Aragorn was on The Return of the Kingâs front cover, yet he looked a lot like his âStriderâ guise.

Anyway, Iâm sure I must have sped through Fellowship in ten days, leaving at least one day to begin The Two Towers, before Jan. 5, 2002. That was the day my brother and I saw Fellowship in the theater. I know that I had already begun Two Towers, because the filmâs d____ of B______ did not surprise me. (It was, however, a spoiler for my brother.)

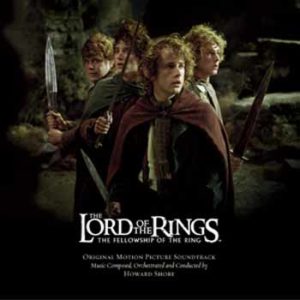

As I mentioned, neither book nor film had first drawn me into Middle-earth, but rather clips of the filmâs soundtrack, by the incomparable composer Howard Shore.

Unavoidably, that music, with its ancient, nearly sacred, somehow woodsy-scented feel, was in my mind as I read, especially because I had already been listening to the film score CD (with this âStriderâ guy on front).

So, what were my first reactions to the book?

- Very âclassical.â Lots of odd words that never occurred in Narnia, the only other classic fantasy I had previously enjoyed. Tolkien seemed to assume I knew what Hobbits were, and already accepted this world called Middle-earth. Thus he constantly threw names and places and languages at me, which I tolerated at first. I wanted to explore this place, and learn, and smell that ancient wood âŚ

- Lots of walking. Tolkien liked to take his time on the journey, and not rush to the destination. Even then, I wondered, as even professional fans do on their bad days: why this excessive attention to the Old Forest, and this weird tripped-out enigmatic Tom Bombadil guy who seems to have no real connection to the story?

- Where was the magic? I kept looking for it, partly because of the few rumors Iâd heard that LotR didnât have clear âChristianâ magic as Narnia (supposedly) has. Gandalf did use magic, but kept it hidden under his pointy hat. More subtle, that.

- The Elves: it took me days to figure out that they were not the same height or build as the Hobbits and/or Dwarves. Oh, tall and elegant Elves. My mistake. In fact, it may have only been after the film that I figured out the casting of full-size adults for Legolas, Elrond, and Arwen was not a departure from the book.

âThe Fellowshipâ of the film

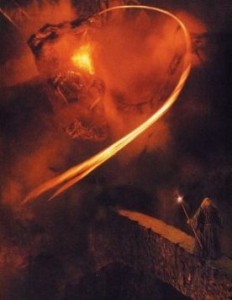

Gandalf versus the Balrog. This scene made me sweat, spellbound, as if the flames and spiritual power were real.

Let me admit something that will bring on the cave trolls (more than one cave troll, you will notice I said). On my bad days, I tend to like the film better than the book. In fact, this is my view even on my good days. In my defense, I canât help it. To me, the book was highly interesting, but seeing the film just a few days after finishing the book âŚ

It absolutely blew me away.

Three hours long, longer than any film Iâd previously seen. Absolutely epic in scope. Things Iâd never beheld. Battles and intensity (complete with lopped-off limbs), leaving one breathless. That majestic music, filling the world, intertwined with its struggles and grandeurs. Brave heroes. The ever-growing evil of the Ring and its dark creator. And that Moria sequence, Gandalf and the Balrog ⌠it left me literally sweating and shaking.

Still, because of that short duration between book and film, I had became one of Those People whom true fans either mock, or at best lament: a Lord of the Rings reader whose view of the books is inseparable from the filmsâ presentations.

I had not the chance to imagine settings and characters on my own. Gandalf is Ian McKellen in costume, Gimli is John Rhys-Davies, and Frodo Baggins never had a chance to be a respectable middle-aged hobbit without a teenage appearance and oddly special-effect-looking blue eyes.

Of course, some of that was a benefit. The film could impress me far more. Because I went in unsure what to expect, I could be stunned. No actor made me wince or recoil because âthatâs not my Aragorn.â I didnât have time to let my imagination of them âset.â

Perhaps better, changes for the film did not faze me at all. (Iâll get to the Faramir storyline in a future column!)

Whatâs your view, I wonder? In this, was I mostly advantaged, or disadvantaged?

What are the pros and cons of seeing any film before reading the book, or else finishing the book only days before seeing its film version? How did your unique exposure to The Lord of the Rings, whether book first then film, or reversed, help or impair you?

We are all familiar with the image of Christ as the lamb of God led passively to the slaughter. Having just left behind the Christmas season, weâre also intimately familiar with Jesus come in the flesh. We recognize Jesus the preacher, wandering through Judea and speaking to people about the coming of the Kingdom. Yet there is one image that is less familiar to us, which is Christ the warrior.

We are all familiar with the image of Christ as the lamb of God led passively to the slaughter. Having just left behind the Christmas season, weâre also intimately familiar with Jesus come in the flesh. We recognize Jesus the preacher, wandering through Judea and speaking to people about the coming of the Kingdom. Yet there is one image that is less familiar to us, which is Christ the warrior. A. T. Ross is an aspiring speculative novelist with four unpublished novels under his belt, a committed Christian, amateur theologian, and avid reader. He is a Reviews editor for

A. T. Ross is an aspiring speculative novelist with four unpublished novels under his belt, a committed Christian, amateur theologian, and avid reader. He is a Reviews editor for

âWhat if I promised you that you would be able to see clearly all the way to where the earth and heaven meet?â

âWhat if I promised you that you would be able to see clearly all the way to where the earth and heaven meet?â

One memory comes to mind. I was visiting the house of homeschooling friends. Like most homeschoolers, they had shelves full of books. Three of them were The Lord of the Rings paperbacks. On the firstâs cover, I believe, was a picture of a long-bearded wizard and a little man. They seemed to be in a cave (Bilboâs house, Iâm sure), and in the dark.

One memory comes to mind. I was visiting the house of homeschooling friends. Like most homeschoolers, they had shelves full of books. Three of them were The Lord of the Rings paperbacks. On the firstâs cover, I believe, was a picture of a long-bearded wizard and a little man. They seemed to be in a cave (Bilboâs house, Iâm sure), and in the dark. Then I never heard about the films until later that year. Daniel, from the same college as I (though not in the same classes or direction), was a huge fan. Yet a friendâs enthusiasm hadnât sold me before, and this oneâs excitement only partially aroused my interest. It still sounded too âclassicalâ to me, even if I now knew the story was not all underground in the literal middle of our Earth. I had my Narnia. Why add another fantasy world?

Then I never heard about the films until later that year. Daniel, from the same college as I (though not in the same classes or direction), was a huge fan. Yet a friendâs enthusiasm hadnât sold me before, and this oneâs excitement only partially aroused my interest. It still sounded too âclassicalâ to me, even if I now knew the story was not all underground in the literal middle of our Earth. I had my Narnia. Why add another fantasy world?