The Strange Case Of Nicheolas Bartleby

(This script could easily be animated, with stellar voice acting and excellent costume work for cute bears, frogs, or perhaps dodo birds, all in a pastel coffee-shop setting. But it turns out those cost money. By contrast, your own imagination is free. Use it accordingly.)

A most peculiar mademoiselle. She loves Christian speculative stories, but doesn’t share them with others or partner with existing readers.

Fredly: Hello, good to see you here. How are you doing?

Nicheolas: Um. Hi. I am fine.

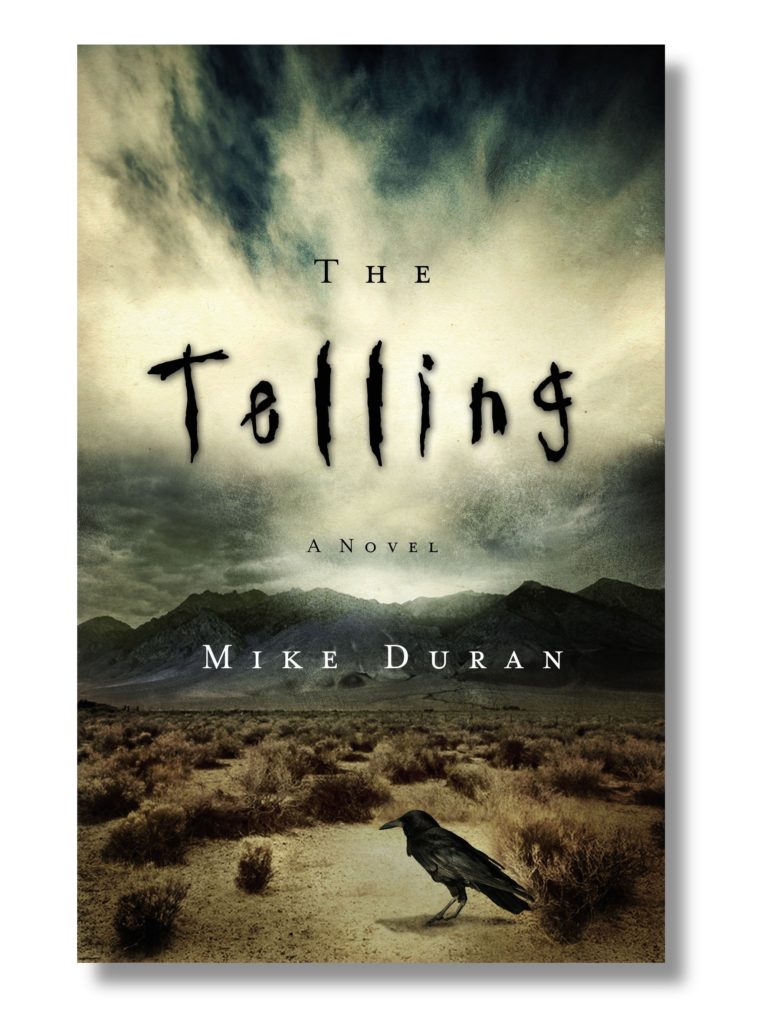

Fredly: Pardon my intrusion, but I couldnât help but notice you reading that novel. I love that novel.

Nicheolas: Um. What?

Fredly: I said I love that novel. Iâve read it twice since it released last year.

Nicheolas: You do? You did?

Fredly: Yes. I particularly enjoy how the author skillfully explores manâs sinful nature versus the imago Dei that reflects his Creator. Iâll never think of Genesis 2 in the same way again. The story and characters made me ponder for days. Such a beautiful work.

Nicheolas: Oh. Well, I liked it because it was fun.

Fredly: Yes. It was fun. But better than that. I havenât felt that kind of joy from many books.

Nicheolas: What do you mean by âjoyâ?

Fredly: I mean an awareness of Godâs beauty, goodness and truth in a story that makes me want to worship Him more. Itâs the kind of happiness that comes with knowing Him. It comes from His true Story in the Bible, and also our stories, whether theyâre real or made up. As C.S. Lewis said in his final Chronicle of Narnia, The Last Battle, âThere is a kind of happiness and wonder that makes you serious. It is too good to waste on jokes.â

Nicheolas: Yeah. Well, I just liked it because it was âweird.â I love âweirdnessâ for its own sake. It also showed real life. The characters werenât perfect and not everything ended perfectly. I wish there were more novels like this that donât hide lifeâs nastiness.

Fredly: But there are more novels like that.

Nicheolas: Really?

Fredly: Yes. You can find them on the internet. Many authors and websites already have that very purpose. Even better, you can talk with friends who love the same kinds of novels. Several of my friends at church could â

Nicheolas: Iâm writing a book. Would you like to hear about it?

Fredly: Whatâs it about?

Nicheolas: Itâs about a poor orphan who discovers that actually he is the lost son of the king and must defeat a fantasy worldâs villain according to ancient prophecy. He can talk to animals, too. And he has a magic sword. If youâll wait a moment, Iâll go out and retrieve my boxes of notebooks. They fill the trunk of my car.

Fredly: Well. That sounds interesting. Have you looked at other books that are already published?

Nicheolas:Â Yes, I think. I was reading this one book that brought you here. In fact, thatâs another reason I liked it. It gave me so many ideas for my own book. Itâs an inspiration.

Fredly: I thought you said you liked it because it was fun.

Nicheolas: What?

Fredly: Well, you said it was entertaining to you. It sounds more like youâre bringing your work into it. Before you can write a book, shouldnât you try to enjoy another personâs story for its own merits?

Nicheolas: Do you want to read my book? We could form a writing group.

Fredly: I think I have read a book like that. Or a few of them. But I was about to ask if you wanted to join a reading group at my church. Weâre going through a classic fantasy written by a famous Christian author that redefined the genre, entertains, and moves us to worship.

Nicheolas: I donât know. I stay pretty busy.

And he absolutely hates being the only one.

Fredly: At what church are you a member?

Nicheolas: No one else at my church likes fantasy. Iâm the only one.

Fredly: What do your friends say about the novels you love?

Nicheolas: I donât talk about them. No one there likes fantasy.

Fredly: Then how do you know? Yes, many Christians dislike fantasy and speculative stories for wrong reasons. But sometimes we can blow that problem out of proportion.

Nicheolas: I think that when publishers find out what an amazing writer I am and my book is published, with a dazzling cover and movie rights fought over by Stephen Spielberg, James Cameron, Peter Jackson, and Michael Bay, then Christians will wake up to fantasy.

Fredly: I think maybe they already are. Now I begin to wonder whoâs really asleep.

Nicheolas: By the way, Iâve been thinking of starting a website about stories like this one. I havenât seen anything like that now, even though I searched the entire world-wide web.

Fredly: The internet already has dozens of such websites. Maybe even thousands. They have author interviews, podcasts, book reviews, and everything.

Nicheolas: I think I will start a website like that myself. Iâll do what no one is doing.

Fredly: People are already doing this. Why not join with them?

Nicheolas: I would prefer not to.

Fredly: That makes no sense at all. You seem to want to be a lone hero.

Nicheolas: I think the best stories are about lone heroes.

Fredly: Not in real life, and not in many great stories Iâve seen.

Nicheolas: Do you want to read my book, or not?

Fredly: Sorry. I do not want to interfere with someoneâs lone-hero mythology. Have a niche day.

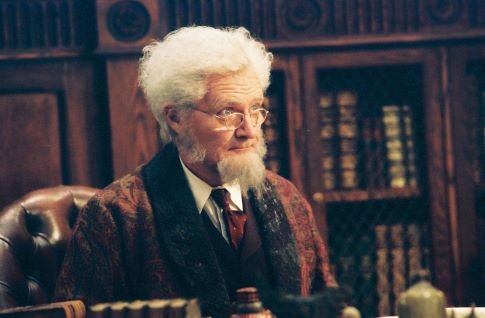

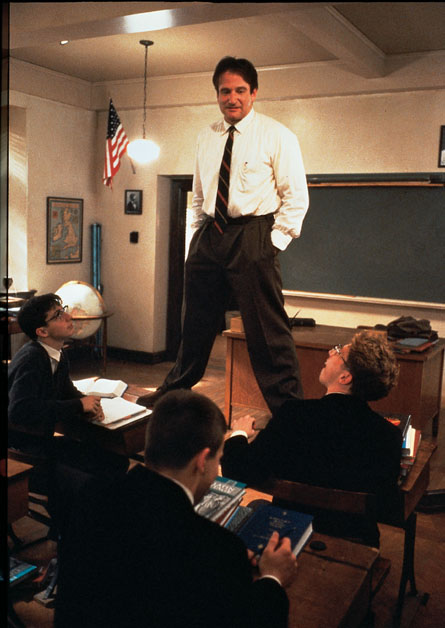

Also, I suppose, being older, having kids, and many other life experiences have all combined and changed the things that stood out to me in that movie. One small scene in particular popped out this time. Keating had his students do an exercise to teach them about the dangers of conformity. The headmaster, Mr. Nolan, saw the exercise and asked Keating about itâor more correctly, reprimanded him.

Also, I suppose, being older, having kids, and many other life experiences have all combined and changed the things that stood out to me in that movie. One small scene in particular popped out this time. Keating had his students do an exercise to teach them about the dangers of conformity. The headmaster, Mr. Nolan, saw the exercise and asked Keating about itâor more correctly, reprimanded him. In Dead Poets Society, that theme is not specific to conformity or non-conformity, but, I believe, has to do with the idea that trouble brews when one tries to completely stamp out the other. In Jurassic Park, the message is nearly stated outright when Dr. Ian Malcolm says, âYour scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.â The theme is broader, more along the lines that the âcouldâ and âshouldâ are both necessary.

In Dead Poets Society, that theme is not specific to conformity or non-conformity, but, I believe, has to do with the idea that trouble brews when one tries to completely stamp out the other. In Jurassic Park, the message is nearly stated outright when Dr. Ian Malcolm says, âYour scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.â The theme is broader, more along the lines that the âcouldâ and âshouldâ are both necessary. Winter by Keven Newsome is a good example of this. It is the story of a Goth girl who is chosen by God to be a prophetess. His message is clear: God chooses the unexpected to do His work. But it falls under an over-arching theme: We canât judge based on appearance. There is reference to the theme everywhere. Not just in how Winter is judged by other students and teachers because of her Goth appearance, but also how she judges them. Outward appearance vs. heart is something that shows up over and over.

Winter by Keven Newsome is a good example of this. It is the story of a Goth girl who is chosen by God to be a prophetess. His message is clear: God chooses the unexpected to do His work. But it falls under an over-arching theme: We canât judge based on appearance. There is reference to the theme everywhere. Not just in how Winter is judged by other students and teachers because of her Goth appearance, but also how she judges them. Outward appearance vs. heart is something that shows up over and over.