For as long as I can remember, my dad loved sci-fi. He often told me about watching the very first broadcast of Star Trek. I also have two brothers who are interested in sci-fi, so I guess it rubbed off. Growing up, I lived near the United States Air Force Academy, NORAD, and Space Commandâeven went to a school named in honor of the space shuttle Challenger. We had real-life space stuff going on all around us.

I recently watched an episode of Battlestar Galactica, and it made me start thinking about why I love science fiction. Possibilities. Possibilities that provide hopeâfor our future and for humanity. In this particular episode, most of the scenes took place in a medical bay on a spacecraft. The president was dying of cancer, and the enemy unknowingly provided a cure by way of blood cells. It was a medical drama, political commentary, and awesome science fiction all rolled into one! So while sci-fi might be a specific genre, it really is open to a multitude of possibilities.

I recently watched an episode of Battlestar Galactica, and it made me start thinking about why I love science fiction. Possibilities. Possibilities that provide hopeâfor our future and for humanity. In this particular episode, most of the scenes took place in a medical bay on a spacecraft. The president was dying of cancer, and the enemy unknowingly provided a cure by way of blood cells. It was a medical drama, political commentary, and awesome science fiction all rolled into one! So while sci-fi might be a specific genre, it really is open to a multitude of possibilities.

I’ve often wondered how I would do with actual space travel. Could I handle living on the Enterprise? I doubt it. I was once an employee of Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines. I could feel the motion of the ocean in the dock. I only stayed on the ship for two weeksâseasick every moment. Now, I can only imagine what space travel is like, but if I equate it with that experienceâdon’t think I could do it.

Doesn’t stop me from loving it, though.

Can you imagine the most beautiful sunset you’ve ever seen…and multiply it by two or three…like the binary sunset in Star Wars: A New Hope? A ship that can zoom through our universeâor other universesâfaster than light? How about a robot who seeks to protect the purity of a young woman, like Dot in Spaceballs?

None of us know what the future holds. No one can predict it. But the beauty of science fiction gives me hope for that future. I know the promise of flying cars has been dashed. I remember when Disneyland’s Tomorrowland looked forward to 1985. So our present has caught up with our future and left us empty-handed. But the advances of the mind continue to progress and perhaps, one day, they will break into reality. Until then, I find my comfort in the arms of the dreamers, hope in the stars, life among the pages of the fictional.

Just before I had my son, I was searching for something to do. Something to keep my mind sharp. I memorized the periodic table. I learned the list of presidents. I studied British kings and queens, books of the Bible, weights and measurements. I created a journal with all that information in it and carried it with me everywhere I went. Okay, so I was really bored. I had gotten married in March, and by December, I was a mom. My identity had shifted from a single career woman to wife (to a pastor, nonetheless!) and mother. Not to mention, I moved across the country, away from my family and home. It was a wacky time. I had looked for a job, but no one was hiring.

One afternoon, I pulled up some old files I had kept from my online role playing days. The characters started whispering to me. Their stories were changing, evolving from the world they knew into a completely different place Iâve come to know as the Circeae System. A couple months after my son was born, so was my first novel, Valor. Writing became my therapy. It gave me identity. It gave me purpose. I finally was in control of something. I just didn’t realize at that point how big it would get.

I went on to write several more books in the same series that Iâve called The Circeae Tales. Circeae translates to âdaughter of the sun.â The novels that followed Valor are stronger and more polished. Each one was a stepping stone in learning the craft. And as I write, I have to go back and tweak things in the others to make them all work together. Did I mention that I don’t write chronologically? I start with my characters, build a scene and grow from there. Somehow, it all comes together for me. I started writing the fourth novel in my series (although as I said, at the time, I didn’t know it would be a series!) Then I wrote the second. The seventh. The ninth. The first. I have the majority of the fifth. The eighth. The third. The tenth has a few scenes. And the sixth consists of notes. But they’re all there. And I can see every one of them in my head, like I’m watching the movies. (They would make awesome movies, by the way!)

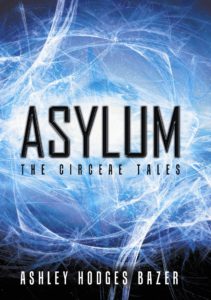

Miraculously, the ninth book in the seriesâAsylumâhas made its way into the hands of readers. In July, it won the grand prize in the WestBow Press/Munce Group 2012 Writing Contest. This meant it would be published with WestBow and marketed through the Munce Group. I started edits at the beginning of August, and by the end of that same month, had my printed book in hand. It was a super-speedy and sometimes head-spinning experience, but quite wonderful to see the end result.

Asylum is the story of Chase and Trista Leighton. They both serve the Ghostsâa band of people engaged in a cosmic battle with the overbearing government called the Progressive Legacy. Chase is wanted by the Legacy because he is Logia, a devout and gifted follower of the Ruler Prince, the deposed ruler of the system. Trista goes out on a mission which turns out to be an ambush. She’s arrested and handed over to the Legacy’s Experimental Medicine agency. Reid Terces is the doctor in charge, and he intends to change Trista’s personality, removing her memories of Chase and the Ghosts, and turning her into a servant for Legacy purposes. Trista is given a new identity as Krissa and works as a computer analyst. The Ghosts first receive news that Trista has been executed, but then they learn of her true situation. Naturally, Chase tries to go after her, but he winds up in Legacy custody, along with his crew. They are all sentenced to the Straightjacket, despite their perfect mental health. After months of brutal treatment, the inmates of the Straightjacket riot. Just prior to this, Krissa boards the ship, assigned to fix the computers. She is taken prisoner by the other inmates. When Chase learns she is onboard, he finds himself in a struggle between reaching his wife and dealing with the identity the Legacy has created.

In this case, the title Asylum has a double meaning. We know the phrase “insane asylum” which can have a pretty bad connotation to it. Oftentimes, itâs used for haunted houses and other frightening experiences. But it also is defined as a place of safety and refugeâa sanctuary. So with the Straightjacket experience, the word asylum came to mind. And of course, I’m all for happy conclusions. Without trying to spoil the ending for the readers, the main characters, following all the harrowing events, end up in a place of safety. They find their asylum.

After having written this book, I found myself thinking about the movie Little Women. I saw the version starring Winona Ryder in the theater. Loved it. That was actually my introduction to the story. I hadn’t read it as a child, but as an adult, I certainly appreciated it. I had a good friend who had a literary crush on Professor Bhaer. We squealed through the movie together, sobbing at all the appropriate moments. It was wonderful.

As a writer, I replay the scene in my head after Jo has presented Friedrich with her manuscript. He is kind with his disapproval, and he tells her to “write what you know.”

Oh, good grief. I’m in trouble!

If I wrote what I knew…sure, I’d have some humorous stories of my children’s antics, but that’s what Facebook is for! I admire the writers who can take their everyday experiences and whip them into a New York Times bestseller. But that’s not me. That’s not where my passion lies.

I got to thinking about this “write what you know” directive. I don’t know about space travel and foreign worlds. I’ve barely been out of this country! I don’t know how spaceships work. I could list the “I don’t know” stuff all day, but you get the point. But the more and more I thought about it, the more and more I realized…I do know. I’m well versed in all things Star Trek and Star Wars. I could recite Firefly episodes to you. I’ve driven through crazy snowstorms and pretended I was entering hyperspace. Goodness, Iâve even quoted Dark Helmetâ”Ludicrous speed!”

I know sci-fi. And I know what I like.

So that’s my justification, Professor Bhaer. I write what I love. I love those characters full of honor and truth. I love those worlds, strange and mysterious. I love the scope of imagination and that my God created me in His likeness…to create! And if a reader enjoys escaping with me on these fantastic voyages, all the merrier am I.

In the traditional marketplace, sci-fi is usually peppered with explicit content. Speculative fiction, thankfully, is on the rise with independent publishers, but walk into any Christian bookstore, and youâll find mostly historical fiction or romance.

Well, thatâs wonderful for those who have a taste for such fiction. My preference, however, leans toward the fantastical. So I decided to write stories like those Iâd want to readâfast-paced action set among solar systems. Characters who represent honor, chivalry, and light. Plots that reveal Godâs hand at work and that share His truth. A family saga connected by a fluid storyline.

Itâs my prayer that Asylumâand eventually the other Circeae Tales novelsâwill pique a mainstream interest in Christian sci-fi. Perhaps it might even plant a few seeds in those readers who wouldnât normally pick up a Christian book. Above all else, though, I pray that God will be glorified.

I watched a program on the History Channel a while back titled Comic Book Superheroes: Unmasked. Writer Dennis O’Neil said that the writers and editors of comic books are not just writers and editors, but they have become “custodians of folklore.”

That phrase stuck in my head as I reviewed my Asylum manuscript. All the characters that have been part of my soulâChase, Trista, Seraph, Redic, Selah, Cam, Brax…they are real now. They haunted me until I got their stories down on paper. And now, theyâve been introduced to readers around the world.

That phrase stuck in my head as I reviewed my Asylum manuscript. All the characters that have been part of my soulâChase, Trista, Seraph, Redic, Selah, Cam, Brax…they are real now. They haunted me until I got their stories down on paper. And now, theyâve been introduced to readers around the world.

That’s a pretty big deal.

I want people to know how Selah and Seraph save the Circeae System by restoring the glory of the Ruler Prince. I want people to learn the legend of the space sailor KinCade. I want people to feel that thrill as the Logia finally overcome the Strages. It’s been in my head for so long; it’s almost like revealing a secret that’s been eating at me. It’s a relief. It’s exciting! It’s awesome!!

I am the custodian of the Circeae folklore. And I’m ready to share it. Are you ready to experience it?

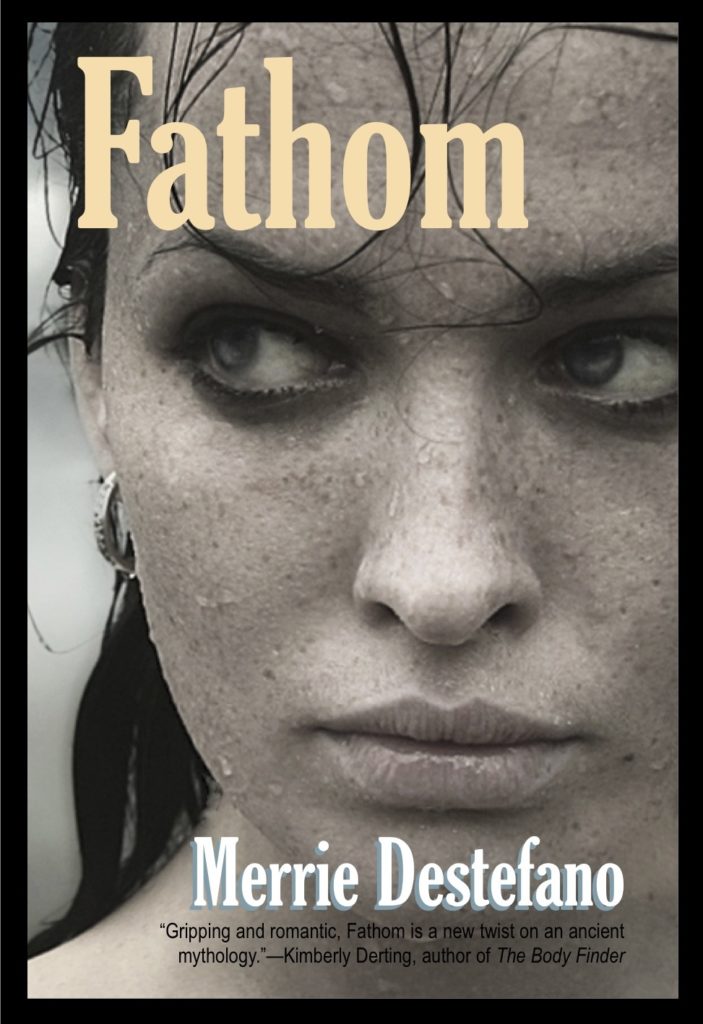

One of the things I recently discovered is that many of my favorite books deal with real life problems, often set within the confines of a fantasy world. Youâd think that writing fantasy would mean that the issues at hand would be whether or not your dragon can talk or whether youâre going to be eaten by a troll before or after you become a princess. However, the fact is, there are real life issues at the heart of every good story, whether itâs a contemporary fantasy, social science fiction, gothic horror, cozy mystery or inspiring romance.

One of the things I recently discovered is that many of my favorite books deal with real life problems, often set within the confines of a fantasy world. Youâd think that writing fantasy would mean that the issues at hand would be whether or not your dragon can talk or whether youâre going to be eaten by a troll before or after you become a princess. However, the fact is, there are real life issues at the heart of every good story, whether itâs a contemporary fantasy, social science fiction, gothic horror, cozy mystery or inspiring romance. With twenty yearsâ experience in publishing, Merrie Destefano left a 9-to-5 desk job as the editor of Victorian Homes magazine to become a full-time novelist. Her first two novels, Afterlife: The Resurrection Chronicles and Feast: Harvest of Dreams were published by HarperVoyager. Fathom is both her first YA novel and her first indie published novel. When not writing, she loves to camp in the mountains, walk on the beach, watch old movies and listen to alternative musicâalthough rarely all at the same time. Born in the Midwest, she now lives in Southern California with her husband, their two German shepherds and a Siamese cat. You can find her on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Tumblr, her blog, and her website.

With twenty yearsâ experience in publishing, Merrie Destefano left a 9-to-5 desk job as the editor of Victorian Homes magazine to become a full-time novelist. Her first two novels, Afterlife: The Resurrection Chronicles and Feast: Harvest of Dreams were published by HarperVoyager. Fathom is both her first YA novel and her first indie published novel. When not writing, she loves to camp in the mountains, walk on the beach, watch old movies and listen to alternative musicâalthough rarely all at the same time. Born in the Midwest, she now lives in Southern California with her husband, their two German shepherds and a Siamese cat. You can find her on Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Tumblr, her blog, and her website.

Surely this is why God includes such dark descriptions in Scripture. Judges 19 is not lovely, but itâs truthful, showing why Israel needs spiritual leadership. Its darkness is set against the backdrop of God later permitting Israel to have a king. That darkness shows this turn of the story in more-vivid gold. Yet later that color also dims, fades to a background, set over the hideous darkness of anarchy but before the infinitely brighter light of the final King.

Surely this is why God includes such dark descriptions in Scripture. Judges 19 is not lovely, but itâs truthful, showing why Israel needs spiritual leadership. Its darkness is set against the backdrop of God later permitting Israel to have a king. That darkness shows this turn of the story in more-vivid gold. Yet later that color also dims, fades to a background, set over the hideous darkness of anarchy but before the infinitely brighter light of the final King.

That phrase stuck in my head as I reviewed my Asylum manuscript. All the characters that have been part of my soulâChase, Trista, Seraph, Redic, Selah, Cam, Brax…they are real now. They haunted me until I got their stories down on paper. And now, theyâve been introduced to readers around the world.

That phrase stuck in my head as I reviewed my Asylum manuscript. All the characters that have been part of my soulâChase, Trista, Seraph, Redic, Selah, Cam, Brax…they are real now. They haunted me until I got their stories down on paper. And now, theyâve been introduced to readers around the world.

Steve DeWitt in Eyes Wide Open: Enjoying God In Everything, defines glory like this:

Steve DeWitt in Eyes Wide Open: Enjoying God In Everything, defines glory like this:

The

The