Magic In The Story: The Two Faces Of Magic

Welcome to part 2 of our series on Magic in the Story. Last week we pondered if any and every mention of magic was outright evil and completely off limits for Christians writing fiction, or if there was room for the fantasy genre to employ magic as a means of representing something else. If you are just joining us, I invite you to start by hopping back to last week’s post and catching up to speed with what has been said to date. As a quick reminder, we’ll be referring extensively to Narnia throughout this series as it seems to be the most visible, liberally executed and well-known example of magic in the Christian fantasy fiction genre.

Welcome to part 2 of our series on Magic in the Story. Last week we pondered if any and every mention of magic was outright evil and completely off limits for Christians writing fiction, or if there was room for the fantasy genre to employ magic as a means of representing something else. If you are just joining us, I invite you to start by hopping back to last week’s post and catching up to speed with what has been said to date. As a quick reminder, we’ll be referring extensively to Narnia throughout this series as it seems to be the most visible, liberally executed and well-known example of magic in the Christian fantasy fiction genre.

Part 1: Magic – Whatâs the Big Deal?

Part 2: The Two Faces of Magic   <âyou are here

Part 3: It’s Written in the Stars  (next week)

This week we delve deeper into the mysteries of ‘Magic in the Story’ and find ourselves confronted by the fact that there are two faces of magic in Narnia. That is to say not all magic is equal. There is good and evil magic in Narnia – the use and abuse of magic is perhaps one of the stronger evidences that Lewis himself understood that there was indeed a fine line between safe and dangerous magic. Consider this sequence from Silver Chair wherein Eustace and Jill find themselves seeking an entrance to Narnia.

âYou mean we might draw a circle on the ground â and write things in queer letters in it â and stand inside it â and recite charms and spells?â

âWell,â said Eustace after he had thought hard for a bit, âI believe that was the sort of thing I was thinking of, though I never did it. But now that it comes to the point, Iâve an idea that all those circles and things are rather rot. I donât think [Aslan would] like them. It would look as if we thought we could make him do things. But really, we can only ask him.â

One of the things I most loved about Narnia was the reverent fear every character holds when it comes to the lion himself. Good or bad, they knew that all things must pass through Aslan – the supreme being of Narnia. But this poses a question, isn’t there evil magic in Narnia? How can that be, and what makes magic good or bad? What do we do with these?

It is true, there are two faces of magic in Narnia, and it’s time we took a closer look at them both.

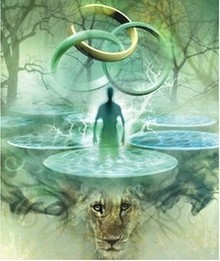

Deep Magic

When it comes to Narnia, Deep Magic, as we’ll call it, belongs to Aslan alone – they are the supernatural, often misunderstood, rules by which the world works. This magic is not something other characters can fully explain or control because it is not theirs to tame, just as Aslan cannot be tamed. I contend that in the case of Narnia, Deep Magic is used as a metaphor for the good spiritual and supernatural things we encounter and engage in our life – divine power, faith, prayer, miracles & wonders, and the Word of God itself. We see this kind of story magic employed throughout the series. We see it when Aslan’s roar awakens the trees, when he restores Reepicheep’s tail and, of course, when he sings Narnia into being.

“Narnia, Narnia, Narnia, awake. Love. Think. Speak. Be walking trees. Be talking beasts. Be divine waters.“âAslan at the creation of Narnia

In all of these instances Aslan is fully in control of the magic at work and most people have no trouble seeing the good in that. It is a symbol of power belonging to the King and Creator alone. This kind of magic seems right and Scriptural. After all, we serve a Sovereign God, right?

“Now in putting everything in subjection to him, he left nothing outside his control…” Hebrews 2:8

If Sovereign magic (Deep Magic used by the Christ-character) was the only magic employed by Christian fantasy fiction we would likely not be having this discussion.

But, alas, this is not the only magic we find in Narnia.

Dark Magic

If Deep Magic in its purest form is a symbol of God’s supreme power, love, and freedom, then the Dark Magic of Narnia, such as the White Witchâs, is often a symbol of abuse of power, of oppression, enslavement, addiction. But here’s the rub. Dark Magic does not come from a source of its own. It has no power outside of the Deep Magic’s control. It is merely a twisted reflection of the divine order of things. Simply put, the evil magic is corrupted Deep Magic. Nothing more. Nothing less.

Isn’t this the nature of all evil – to mimic and twist the truth?

Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things. Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever! Amen. (Romans 1:22-25)

Dark Magic is the power by which Pharaoh’s magicians deceived him to believe they were as powerful as God. It is the same magic from which Simon the Sorcerer and the witch of Endor performed their wonders in the Bible.

The point I’m trying to make here is that in each and every case, the ultimate source of Dark Magic comes from an abuse of something originally good.

It isn’t anything new. Evil has been doing this for ages. It is sin. It is also subject to the Sovereign authority of something greater – namely God.

That is why I am so baffled by Christians who shudder at the thought of an evil sorcerer or witch in fiction, but are perfectly fine with murder mysteries. Why? Are they not both representations of evil? Are not both demonstrated in the Bible?

If a villain raises his scepter and performs a seemingly miraculous or magical sign it is almost certain to raise a few eyebrows. The question will be asked if the story is intended to glorify the occult – luring young, impressionable readers to attempt the same. In some cases, it may be – and we must flee. But in many (dare I say most) fantasy books, the twisting of good magic never takes on an appealing form. It is almost certainly ugly, depraved and self-centered. If it is alluring for a time, it is almost always revealed for what it truly is…a deception.

For this reason, I have no trouble with the evil magic of Narnia. I have no issue with the blood sacrifice of the witch at the Stone Table. I am not offended by the hag and werewolf performing a ritual in hopes of resurrecting the White Witch. Why should I be? Evil exists in our world as much as it does in the world of a fantasy. Dark magic is just another way of showing it. Whether by incantation or by murder, evil is being done.

The allure of Dark Magic is one of the potent examples of the temptation of sin. It is, at its root, a selfish power.

In The Magician Nephew, Uncle Andrew is a good example of this. We see him as a self-absorbed and somewhat creepy man, but in the end we come to pity him. Why? Because we are able to see a part of ourselves in him. He ‘dabbled in dirt of the Magical kindâ and we see the effects it has on the person. There was no joy in it. Lewis refers more than once to magicians and witches as being âterribly practical peopleâ who only see the value of things in relation to themselves and the achievement of their own selfish ends.

Handled correctly, the occult and Dark Magic can be wonderful imagery to use in fiction.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the occult is a very real and dangerous threat to teens (or anyone, really) looking for something to believe in. Lewis knew this first hand too. In fact, in his wonderful book Surprised by Joy he shares how in his own pre-Christian life experience he was strongly tempted by the occult but was ultimately protected from going down this dark path. In his own words:

There is a kind of gravitation in the mind whereby good rushes to good and evil to evil. This mingled repulsion and desire drew towards them everything else in me that was bad. The idea that if there were Occult knowledge it was known to very few and scorned by the many became an added attraction to me… That the means should be Magic â the most exquisitely unorthodox thing in the world, unorthodox both by Christian and by Rationalist standards â of course appealed to the rebel in me… If there had been in the neighbourhood some elder person who dabbled in dirt of the Magical kind (such have a good nose for potential disciples) I might now be a Satanist or a maniac.

In actual fact I was wonderfully protected, and this spiritual debauch had in the end one rather good result. I was protected, first by ignorance and incapacity. Whether Magic were possible or not, I at any rate had no teacher to start me on the path. I was protected also by cowardice…Â But my best protection was the known nature of Joy… Slowly, and with many relapses, I came to see that the magical conclusion was just as irrelevant to Joy as the erotic conclusion had been… If circles and pentagrams and the Tetragrammaton had been tried and had in fact raised… a spirit, that might have been… interesting; but the real Desirable would have evaded one.

Later in the book he concludes his thoughts on the matter by saying, âI had learned a wholesome antipathy to everything occult and magical…Not that the ravenous lust was never to tempt me again but that I now knew it for a temptation.â

I think it’s safe to say whatever Lewis intends by the magic in his books, it is clearly not the Occult.

So we have the two faces of magic – Deep and Dark.

Discerning the Difference

Many Christians define magic as only Dark Magic. They dismiss the idea that anything with the name “magic” could possibly be deep. Call them wonders or miracles and we’re perfectly fine but the moment we say “magic” it falls into another category altogether. I think the concern among Christians isn’t really the existence of the two faces of magic, but rather discerning the difference between the two.

Even having defined the two archetypes of magic in Narnia it is not always so simple to determine what magic is at work.

In the book The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Lucy is given a task to enter a mansion and recite a spell to turn Dufflepuds and a wizard (and even Aslan himself) visible again. Lucy enters the mansion and finds the spell-book, a ‘book of incantations’ which holds many spells for all kinds of ailments. It is never specifically mentioned where this book finds its origin, but its very existence requires someone to recite the words for them to work. After misusing one of the spells to her own advantage, Lucy does find the passage to make the invisible visible and in both cases the magic works. What are we to think of that? What magic was at work here? Deep or Dark?

This is one of the most controversial passages in the entire series.

Perhaps the narrator, Lewis, gives us a hint when shortly before this he eludes to the fact that he himself is not a magician and that the Book (capital B) is not unlike that of the Bible (one of the only references to the Bible in the entire series). Lucy misuses the Book to eavesdrop on her friends and becomes very irritated in what she hears. Guilt ridden, she overcomes the temptation to continue her misuse of the book (Aslanâs book even, as we will soon learn) and turns the page. To her relief, Aslan has provided a âspellâ for soul-refreshing just when she needs it. Perhaps this is a symbol of Aslan ‘leading her beside still waters’ like Psalm 23? Aslan knows her immediate need is for comfort and refreshing. He introduces a spell âfor the refreshment of the spiritâ which is a story so refreshing to her soul it reminds us of the Gospel story (literally a âgod-spellâ or âgood-spellâ, the origin of the English word âgospelâ).

But here’s the kicker!

When Aslan appears after Lucy has spoken the spell for making hidden things invisible, he says that it is Lucyâs spell which has made him visible and crucially asks âDo you think I wouldnât obey my own rules?â. The spells, the magic, in the book, obey Aslanâs rules; it is all ultimately Aslanâs (or Godâs) Deep Magic.

Lucy and we, the readers, are learning that perhaps Deep Magic is really the only magic there is. It can be abused and in doing so be thought of as Dark Magic. But all of it belongs to Aslan. After all, it is not what is outside of a man but what it inside that corrupts him. So too, it is the intent of the heart that makes a thing wicked or not. One may love another person and it would be a good thing. But if the love becomes perverted by selfishness it is no longer love at all, but an obsession. What good is selfish love? I propose it is Dark Magic.

Like Eustace and Jill learned(in the excerpt from Silver Chair I began this post with), in Narnia, the rules are simple – magic must be ordained by Aslan alone. Anything else would be a deception.

Next week we’ll take a peek at the use of Astrology in fantasy fiction.

Also, thanks for all the wonderful comments last week. I’ll try to do a better job at responding to them this week.

Those of us who grew up in the sixties and seventies, were exposed to a wealth of dystopian novels and films. Thereâs the bubble cities of Loganâs Run where oneâs life is literally âin the palm of their hands,â and the overpopulated world of Soylent Green. Thereâs the totalitarian government of Orwellâs classic 1984 and the overstimulated population of Huxleyâs Brave New World.

Those of us who grew up in the sixties and seventies, were exposed to a wealth of dystopian novels and films. Thereâs the bubble cities of Loganâs Run where oneâs life is literally âin the palm of their hands,â and the overpopulated world of Soylent Green. Thereâs the totalitarian government of Orwellâs classic 1984 and the overstimulated population of Huxleyâs Brave New World.

This is the prime divine mover behind all bad romance: if you donât believe in Biblical truth about God and His love, youâll have skewed views of all love. And mutilating the truth that âGod is loveâ is a cottage industry among many evangelicals. No, Iâm not only talking about Rob Bell and other universalist authors. Popular and otherwise good teachers have already wrongly taught of âGodâs loveâ far past the point of parody. I donât believe they think Godâs love does not mean that He isnât holy, hateful of sin, or willing to pour His wrath on Christ in our place. But many do prefer simply not to talk about such things very often. And of course, âwe donât talk about that truthâ soon becomes âwe donât really believe that truth.â

This is the prime divine mover behind all bad romance: if you donât believe in Biblical truth about God and His love, youâll have skewed views of all love. And mutilating the truth that âGod is loveâ is a cottage industry among many evangelicals. No, Iâm not only talking about Rob Bell and other universalist authors. Popular and otherwise good teachers have already wrongly taught of âGodâs loveâ far past the point of parody. I donât believe they think Godâs love does not mean that He isnât holy, hateful of sin, or willing to pour His wrath on Christ in our place. But many do prefer simply not to talk about such things very often. And of course, âwe donât talk about that truthâ soon becomes âwe donât really believe that truth.â