“What is the meaning of it, Watson?” said Holmes solemnly as he laid down the paper. “What object is served by this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must tend to some end, or else our universe is ruled by chance, which is unthinkable. But what end? There is the great standing perennial problem to which human reason is far from an answer as ever.”

“What is the meaning of it, Watson?” said Holmes solemnly as he laid down the paper. “What object is served by this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must tend to some end, or else our universe is ruled by chance, which is unthinkable. But what end? There is the great standing perennial problem to which human reason is far from an answer as ever.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has put it plainly in The Adventure of the Cardboard Box. The befuddlement of the brilliant Sherlock Holmes, the world’s greatest fictional detective, when it comes to the purpose of evil sticks out like a splinter in our thumb. Here is, fictionally speaking, one of the most learned and astute minds of all time, one who rarely misses a thing, and he is stumped when it comes to the mystery of evil. He can’t solve this puzzle. It is a haunting question beyond his, and our, grasp.

The problem of evil is not a new subject by any means. Humans have been wrestling with the purpose of evil ever since Adam and Even consumed the fruit of the tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. And no wonder, there is little else that has so drastically effected mankind and our world as the presence of evil in it. When evil entered our world we were forever changed.

One of the things that I love most about fiction is the means it provides to explore and observe the meaning of evil in our tales. Evil is, after all, one of the most essential elements of storytelling. In fact, I would venture to say it is THE most essential element of story, for without crisis, conflict or depravity of some kind, a story cannot exist. Imagine reading a book in which nothing ever goes wrong, no challenge is presented, no feat is overcome, our hero remains fearless from beginning to end.

B-O-R-I-N-G.

Human storytelling cannot exist in a vacuum of goodness alone. We are, by nature, children of evil who wrestle with our own shortcomings in part through the tales we tell. We see it at work in our own world and must find ways to cope. So we write. We tell stories. Some write lightly around it; others, like Doyle, address it directly. In fiction, Homer, Milton, Mary Shelley, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, and Flannery O’Connor all tackle the issue of the meaning of evil head on. Dostoevsky deals with it directly and powerfully in his masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov. In it, Ivan Karamoazov challenges his Christian brother Alyosha about the problem of evil:

“Tell me frankly, I appeal to you – answer me: imagine that it is you yourself who are erecting the edifice of human destiny with the aim of making men happy in the end, of giving them peace and contentment at last, but that to do that it is absolutely necessary, and indeed quite inevitable, to torture to death only one tiny creature, the little girl who beat her breast with her little fist, and to found the edifice on her unavenged tears – would you consent to be the architect on those conditions? Tell me and do not lie!”

“No, I wouldn’t consent,” said Alyosha softly.

The power of the mystery of evil in story is so great that it has been said that this fictional exchange may be the single strongest case against the concept of a loving God ever made. After all, how could we allow ANY good purpose to exist in evil if it meant something so horrible must be the foundation of the good purpose?

There are many answers proposed answers to this question and I will not attempt to answer them all here. In fact, I hardly feel qualified at all to speak on the matter because even though true evil has struck my family, it has not struck us as deeply as it has much of the world, and there are many greater minds that have more adequately tackled the subject in other writings.

I will, however, offer a few observations as a writer which I feel best capture the a brief glimpse (incomplete as it is) of the meaning of evil.

1. OUR STORY IS NOT YET FINISHED

Earlier I mentioned that story is so strongly tied to evil that it could not exist without it. But if tackling evil in story is essential, so too is the overcoming of it. Too often we measure goodness by the “here and now” and give little thought to the hereafter. We can’t see past this particular dark page of our lives because we are currently in it and the meaning of it all eludes us. It is right to feel this way – to ignore the reality of the moment is to rob our own lives of the beauty of the drama of human existence. If we cannot cry and mourn and question God, how can we be authentic to the story that is being told in our lives?

And yet, as Christians, we know there is more to the story than meets the eye. We know there is a world to come, in which all that is wrong will be made right. We are promised a good ending that Christ is preparing for us even now. The Overcomer will overcome and deliver us to the promised land.

I say this because that glorious ending would not be nearly as glorious if we have not tread a difficult path to get there. How much sweeter will the air of life be after passing through the Valley of the Shadow of Death? How much greater will the light appear for those who have known the darkness? Will it not make us stand up and sing?

Perhaps, in this way, the allowance of evil is the one thing that can cause us to look for good more than anything else?

But what of tragic endings, you ask, what of the child raped and murdered by the ravenous madman? How can that possibly end in anything good?

Evil’s roots grow deeper and its thorns become more painful when we allow them to prick us in the real world. When it does, we no longer are comforted by mere platitudes. It requires something deeper to recover from these moments. Something supernatural.

A relative on my wife’s side of the family, a beautiful young girl with developmental disabilities, was lured into a forest, raped and murdered. I’ll spare you the details in this blog post, but if you want to read more you can by clicking here. To say this act was anything but unbridled evil is to lie to ourselves. If there is any good in it I cannot see it. If there was meaning in it, it is beyond my understanding.

And as horrid as this act was, as deranged as the mind of the boy had become to take advantage of such a wonderful light in our world, it pales in comparison with what evils unfold around the world every day.

Recently, I had the unfortunate task of viewing and aiding in the editing of raw footage brought back from Sudan where an entire village was massacred by a horde of mercenaries. What I saw in that raw footage from the aftermath of the midnight attack made my stomach turn. Children dismembered, bodies burned, things I have tried desperately to forget. It was pure, depraved evil, the likes of which I have never seen before.

If the story ended there, I would be like Sherlock Holmes questioning the meaning of it all. There would be none. There COULD be none.

But the story of the survivors of that village is one of hope and forgiveness. A husband and wife who lost everything in the midnight raid returned to the very same village to rebuild the town and to share the love of Christ with the other survivors. They did it, despite their darkest fears, because they new that they must forgive the men who killed their family and neighbors. God’s love, his goodness, is now being seen in the lives of those who went through the dark times and came out of it with a hope that defies all explanation.

If they can forgive their enemies, can I not forgive my neighbor when he offends me?

We may never see the final chapters of evil be overcome in our lives. But we know that it can, and that it will. That one day the ultimate judge will return and set things right. He will restore all things and we will live in the light forever more. Until that time, we must wait and hope and trust and persevere through the darkness.

2. OUR STORY IS NOT OUR STORY

In the end, we are not the ones who suffer the most. God himself, the Author of our world, has not spared himself from the worst of it.

At the center of all human tragedy lies the crucifixion. The moment when God turned his wrath completely on himself. He surrendered his human son to the most vile and depraved form of torture ever devised by man. To this day crucifixion remains the most horrific form of killing. And if God did not spare himself, but gave himself up for us all, there must be good in it. He would not do this for nothing. There must be something that we can take away from this evil that gives us hope.

I contend it is this: consider, for a moment, that God had not allowed Adam and Eve to take the forbidden fruit. Imagine a world in which we never experienced evil or sin. Perfect from the beginning and perfect to the end. Do you not see the cruelty in that as well? We would know God as creator and father, but we would never experience or know him as anything more. We would never experience mercy or forgiveness. We would have no need to call him Savior or redeemer. We would be robbed of the deepest measure of his love for us.

How awful it would be to live in a world that had never been touched by evil at all.

And that is the point of it. Evil is not really about us at all. It is about God. It is about his glory as our savior. With that in mind, with evil placed soundly under the submission of a Sovereign God, we can make sense of the unthinkable. We long for the conclusion of the story because it is when our joy and His joy will be made complete together. United at last, with our savior we will look back with great accomplishment at the lives we left behind – lives we once thought were everything, but turned out to be only a passing breath.

Perhaps this is why evil is so necessary in story, because without it redemption is not possible.

In this way, the authors who most understand redemption are the authors who most understand story.

Several weeks ago author R. J. Anderson who has been a guest blogger here at Spec Faith, left a comment to my post “Who Reads Speculative Fiction?” regarding Christians writing fiction in the general market. She named a handful of authors, herself included, and said

Several weeks ago author R. J. Anderson who has been a guest blogger here at Spec Faith, left a comment to my post “Who Reads Speculative Fiction?” regarding Christians writing fiction in the general market. She named a handful of authors, herself included, and said

With six books to her credit and another due out in a year, Canadian R. J. Anderson is the veteran of the four. Her young adult novels include the fairy books *Knife, *Rebel, Arrow, Swift, and coming in 2014, Nomad. She’s also written the young adult science fiction/psychological thrillers Ultramarine and the just released Quicksilver.

With six books to her credit and another due out in a year, Canadian R. J. Anderson is the veteran of the four. Her young adult novels include the fairy books *Knife, *Rebel, Arrow, Swift, and coming in 2014, Nomad. She’s also written the young adult science fiction/psychological thrillers Ultramarine and the just released Quicksilver.

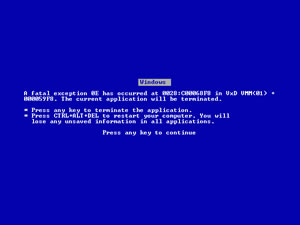

Yet I still have story shutdowns, and so do you.

Yet I still have story shutdowns, and so do you.

Evil demons having relations with victim humans is Biblically questionable, based more on myths about incubi than actual Scripture. Second, it makes Christians sound like little more than guests on late-night conspiracy-centered radio, or potential targets of

Evil demons having relations with victim humans is Biblically questionable, based more on myths about incubi than actual Scripture. Second, it makes Christians sound like little more than guests on late-night conspiracy-centered radio, or potential targets of

![windfollower2[1]](http://www.speculativefaith.lorehaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/windfollower21-210x300.jpg)