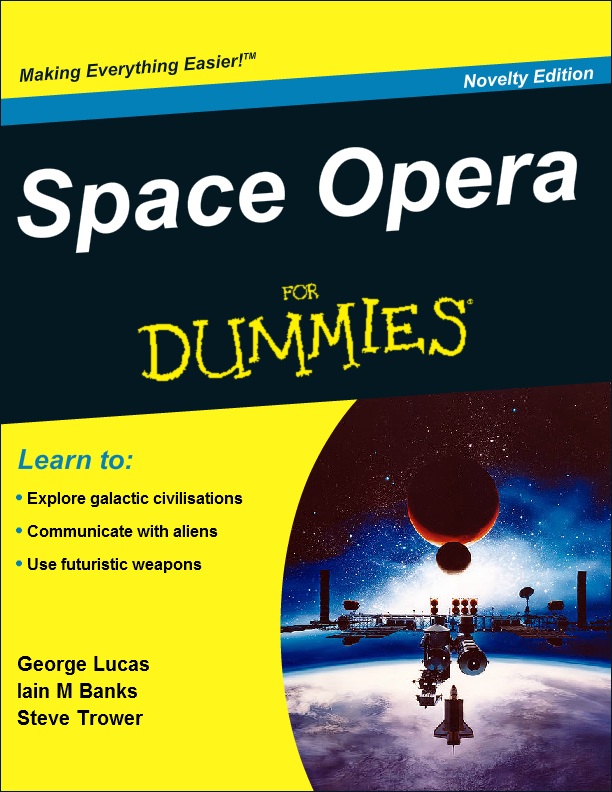

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away ⌠seemed like an obvious way to start a piece on the subject of space opera â which, despite the rather flippant title, is nothing to do with a soprano in a rocket ship bemoaning the lack of atmosphere, or indeed that episode of Doctor Who with Katherine Jenkins.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away ⌠seemed like an obvious way to start a piece on the subject of space opera â which, despite the rather flippant title, is nothing to do with a soprano in a rocket ship bemoaning the lack of atmosphere, or indeed that episode of Doctor Who with Katherine Jenkins.

No, in fact, the term space opera was coined in the 1940s, as a sort of witty put-down, likening certain types of pulp sci-fi to the then new phenomenon of soap operas.

These were the stories of romantic heroes heading off into the unknown reaches of space with nothing more than a ray gun between them and some green bug-eyed monster; of colossal spaceships involved in the epic struggle of good versus ultimate evil; of the grizzled space-jock, blaster in one hand, recently-rescued princess in the other, taking on a corrupt galactic empire â and winning.

And if that sounds a little familiar, it might just be because some time in the 1970s a man with a beard found all those things in a box somewhere, sprinkled them with Industrial Light and Magic, and⌠space opera was given a whole new lease on life.

The fact that I grew up in the time of the original Star Wars trilogy, when space shuttle launches were still news and kids still wanted to grow up to be astronauts (or X-Wing pilots), may have something to do with my fondness for this kind of space opera.

The fact that I grew up in the time of the original Star Wars trilogy, when space shuttle launches were still news and kids still wanted to grow up to be astronauts (or X-Wing pilots), may have something to do with my fondness for this kind of space opera.

Hard science fiction, the kind that takes its science very seriously and likes to contemplate the possible effect of technology on humanityâs future development, is all well and good, but doesnât every kid just want to blow the bad guys up and go home?

Nobody cares what powers a Tie Fighter or how the Millennium Falcon can travel faster than light; space opera just takes it as read that the technology works, maybe throws in a dilithium crystal or some other kind of handwavium, and gets on with the story.

As well as the over-arching battle between good and evil that often provides the action, a typical defining characteristic of a space opera is that of scale. The Star Wars trilogy, to return to that well-known example, takes us from the desert world of Tatooine to the swamps of Dagobah, the ice world of Hoth, and the cloud city of Bespin, among others. A rather simplistic approach to designing a galaxy maybe, but undeniably effective in film.

Written space opera, on the other hand, can afford to go into greater detail, and so we find galactic civilisations such as those in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation stories and James Blish’s Cities in Flight, developed and built upon over a series of novels. More recently, another man with a beard, the late Iain M Banks, has taken the pan-galactic culture to a new level, with the weird humans, even weirder aliens and omnipotent artificial intelligences that inhabit his Culture novels, which have gone a long way to further redefining space opera as a legitimate form of genre literature.

Written space opera, on the other hand, can afford to go into greater detail, and so we find galactic civilisations such as those in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation stories and James Blish’s Cities in Flight, developed and built upon over a series of novels. More recently, another man with a beard, the late Iain M Banks, has taken the pan-galactic culture to a new level, with the weird humans, even weirder aliens and omnipotent artificial intelligences that inhabit his Culture novels, which have gone a long way to further redefining space opera as a legitimate form of genre literature.

However, there does seem to be an assumption in most stories of this type â itâs a kind of unwritten rule in the Star Trek universe, for instance – that any civilisation advanced enough to colonise the galaxy has long since realised that religion belongs to a less enlightened era. Even Darth Vader is mocked for his âsad devotion to that ancient religionâ.

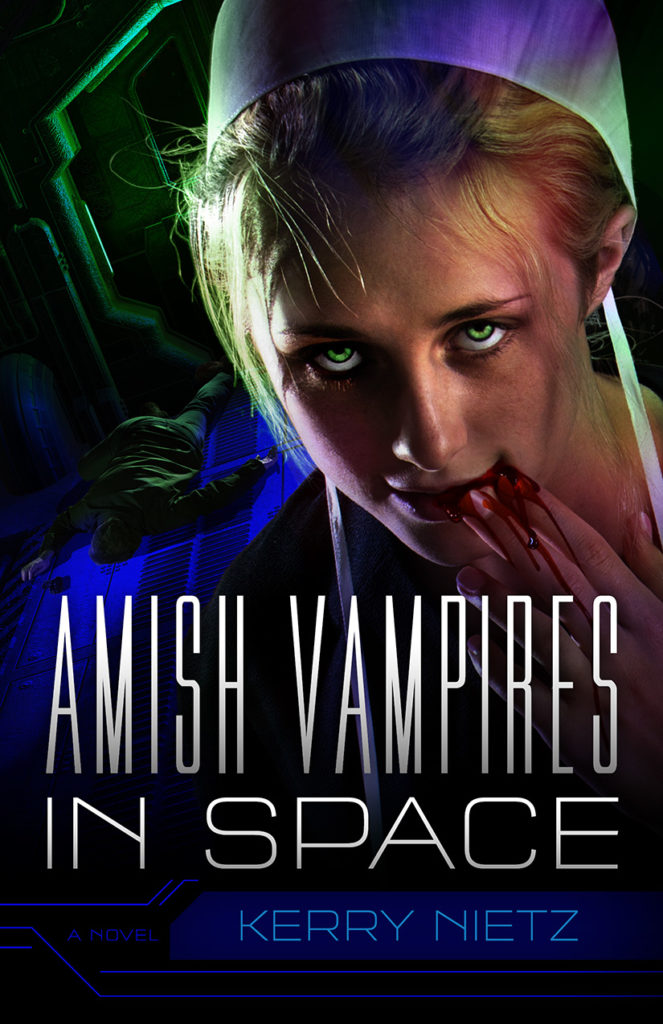

There are exceptions: Christian sci-fi readers have been treated to The Lamb Among The Stars series by Chris Walley, a far future tale in which Christian humanity has colonised the galaxy, as well as the Firebird Trilogy by Star Wars novelist Kathy Tyers. Both have all the things a good space opera should have, and a solid spiritual grounding from which to work.

There are exceptions: Christian sci-fi readers have been treated to The Lamb Among The Stars series by Chris Walley, a far future tale in which Christian humanity has colonised the galaxy, as well as the Firebird Trilogy by Star Wars novelist Kathy Tyers. Both have all the things a good space opera should have, and a solid spiritual grounding from which to work.

But these are an exception in sub-genre that doesnât need God in order to perform miracles; so where does that leave us, looking for faith and meaning in these stories? Does space opera have a place for the Christian reader?

Alongside âMay the Force be with youâ, there is another quote that has hung around in the back of my mind since childhood:

How clearly the sky reveals God’s glory! How plainly it shows what he has done! (Psalm 19:1, Good News Translation)

Itâs hard to deny the huge, galaxy-spanning scale of Godâs creation. God works on an epic scale; after all, why be satisfied with making the universe just âreally bigâ when âinfiniteâ is within your grasp?

And whatever strange worlds we read about in space operas, however weird the aliens we meet, whether based on some theoretical science or a pure fiction, they have been created by a mind far less imaginative than that of God â the Mind which created both the science and the imagination.

“Pillars of Creation,” the photograph taken through the Hubble Telescope in the Eagle Nebula

However fantastic a galaxy we can create in our imaginations, read about in a Culture novel or see in a sci-fi adventure movie, the reality is far more exotic â just take a look at the Pillars of Creation, or the Horsehead Nebula.

But thatâs not all: the exploring, the seeking out new civilisations – thatâs right out of the Bible, isnât it? Right from the start, since the expulsion from Paradise, man has been boldly going where no one has gone before. Did anyone ever go more boldly than Abram? Or Moses?

And the backdrop to the Israelitesâ travels throughout the Old Testament is of course, the ancient struggle between good and evil. A struggle which went on throughout the life of Jesus, and which we all experience on a daily basis.

And that, I believe, is what Space Opera has to say to us. God has placed within us a spark of the infinite, and a knowledge that good and evil are at war around us. The power of story to illuminate Godâs truth has no doubt been mentioned on Speculative Faith many times. To me, Space Opera is the perfect means to express the big truths about Godâs plan for us.

And with that, Iâm off to grow a beard and reinvent a sub-genreâŚ

– – – – –

Steve Trower is a Christian, geek dad, and part-time creator of parallel universes. He lives in the once and future capital of Mercia (known in this reality as central England [which explains the occasional strange spelling in this post – đ ]) with two daughters, one wife, and a Mini called Binky. In between â and frequently at â a series of menial jobs, he managed to chalk up a number of non-fiction writing credits before deciding that making stuff up was a lot more fun than being bound by those âfactâ thingies magazine editors seem so keen on, and began practicing the dark art of novel writing.

Steve Trower is a Christian, geek dad, and part-time creator of parallel universes. He lives in the once and future capital of Mercia (known in this reality as central England [which explains the occasional strange spelling in this post – đ ]) with two daughters, one wife, and a Mini called Binky. In between â and frequently at â a series of menial jobs, he managed to chalk up a number of non-fiction writing credits before deciding that making stuff up was a lot more fun than being bound by those âfactâ thingies magazine editors seem so keen on, and began practicing the dark art of novel writing.

His first Old Testament Space Opera, Countless as the Stars, will be released as an e-book later this year (paperback copies are still available at giveaway prices from stevetrower.com).

He blogs at stevetrower.com/blog and tweets as @SPTrowerEsq, but neither as often as he should.