Biblical Discernment: Heeding Fables

âFiction is a lieâ forms the basis of an often used argument against Christians writing or reading fiction, even to convey Biblical truths. I spoke to that issue on my own blog back in 2008: The Lies of Fantasy Fiction.

âFiction is a lieâ forms the basis of an often used argument against Christians writing or reading fiction, even to convey Biblical truths. I spoke to that issue on my own blog back in 2008: The Lies of Fantasy Fiction.

The referenced article in that post linked fantasy with lying, thus the numerous Biblical verses against lying were prohibiting us from enjoying a good fiction story, and/or writing them.

I pointed out that to lie is done with the intent to deceive. It is telling an untruth as if it is true. When one picks up a book labeled, âFiction,â they know up front it is not a true story. There is no pretending it really happened. So it is not lying, nor does the Bible prohibit fiction based upon that line of reasoning. It is, in essence, a real lie to teach that the Bible equates the two.

Another site takes a similar tactic, but uses the following verse, suggested that I tackle in last week’s article, to make a case that the Bible is against using fiction:

Neither give heed to fables . . . (1 Tim 1:4a)

The underlying word used to translate âfablesâ is the Greek word from which we derive our English cognate, âmyth.â On the surface, this would seem to be a prohibition against fiction, but let’s take a deeper look.

Context

The full verse in context is as follows:

As I besought thee to abide still at Ephesus, when I went into Macedonia, that thou mightest charge some that they teach no other doctrine, Neither give heed to fables and endless genealogies, which minister questions, rather than godly edifying which is in faith: so do. (1 Tim 1:3-4)

Timothy was overseeing the newly formed church in Ephesus when Paul wrote this. As in most places they visited, there was a contingent of Jews who tried to steer new Gentile Christians to adopt a traditional Jewish application of the Gospel, involving stories designed to teach truths and genealogies to promote Jewish purity and authenticity. It was easy for new Christians, not able to discern such things yet, to be drawn into these false teachings instead of being strengthened in the Faith that Paul gave them.

Two key points indicate that Paul was not condemning all fiction, but a specific type of fiction.

One, as Paul states, his point here was to âteach no other doctrine.â The prohibition is against fables that teach false doctrines of the faith, not all fiction. Obvious since then Paul would be condemning Jesus’ use of parables.

Two, the fables spoken of were related to the doctrine of the Jews who wanted the Gentile Christians to fully follow the Law as Jews do. The evidence for this is clear.

- Paul links fables with the study of genealogies, an obvious reference to Jewish preoccupation with historical lineage.

- In the following verses, Paul speaks about using the âLaw lawfully.â An issue of contention in the Jewish Christian teachings.

- Paul, in warning Titus of the same thing in Titus 1:14, specifically calls them âJewish fables.â

To then derive the principle that this prohibits us to read or write any fiction is not supported by the context of the verses.

But what does this context tell us about using discernment in our fiction reading?

Application

Principle 1: Discernment is based in faith.

Paul’s main problem with the fables and genealogies was that it confused rather than edify the faithful by sowing discordant teachings. Paul would rather Timothy focus his energies on teaching the Gospel.

But how do we know the difference in our fiction? Paul’s answer is through faith. This is not some abstract belief in your mind faith. It is faith in the person of Jesus Christ. Such a faith spends time with Him in prayer, worship, and study of the Scriptures.

Faith in Christ is to marinate ourselves in Him so well, our spirit will sense something is not right, even if we have trouble putting our finger on it. Paul emphasizes this fact in the verses following 3 and 4. To use the Law lawfully, Paul instructs us not to use the Law as a means to save ourselves, but to know Christ by a deep relationship through love, purity, a clear conscience, and faith.

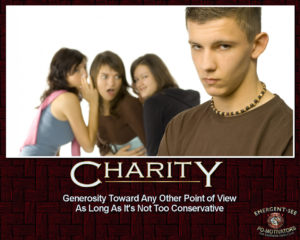

Now the end of the commandment is charity out of a pure heart, and of a good conscience, and of faith unfeigned. (1 Tim 1:5)

Having been steeped in these qualities, and knowing Christ intimately through faith in Him, we gain the ability to know when something in fiction is amiss. He gives us a discerning spirit.

Principle 2: Avoid false doctrine.

The reason Paul told Timothy not to heed those fables is because by going counter to the Gospel he taught, it would confuse and cast doubt rather than edify and strengthen people in Christ. A book that teaches false doctrine is to be avoided for this reason.

But note, I said a book that teaches false doctrine is to be avoided, not merely a book that has characters who believe false doctrine, or characters who sin. Rather, if the book as a whole is promoting a belief contrary to the Gospel, we are instructed to not give heed to it. One of the main reasons I’ve not bothered to read Pullman’s books.

Also, we need to keep in mind the following. Stories can be valid vehicles to convey truth, but they are not a systematic theology book. Experience and life can be messy.

One should not derive their theology from stories, no matter the truth conveyed. If they open our minds to see Biblical truth in a fresh and vibrant way, great. But we shouldn’t expect a story to be 100% in line with all Biblical truth. Our theology should grow from Scripture and the Holy Spirit guiding us into all truth, not based on a novel.

Additionally, authors are not infallible. Because a story isn’t fully in line with every âiâ and âtâ of one’s theology doesn’t necessitate burning the author at the stake. If the story does teach some important truths when taken as a whole, one should make allowances for the fallibility of finite human brains.

By keeping those in mind and strengthening our faith in Christ, we can discern when a fiction story is not edifying to our walk with the Lord.

What boundaries do you use to filter the fiction your read?