Incarnation, Part 2: Hero In The Flesh

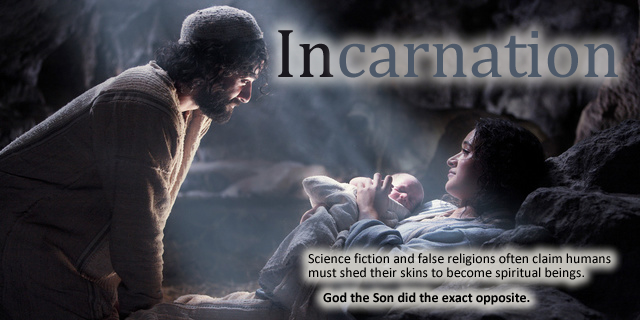

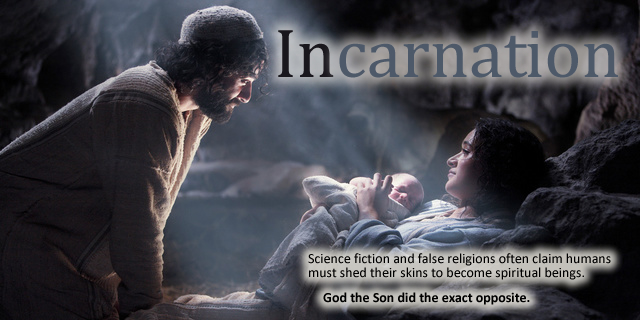

Yes, many science-fiction stories and most false religions — including some Christianity — seem to enjoy flatly contradicting the Bible’s plotline, only for fits and energy-being giggles.

Scripture says God first saves people’s souls or spirits, then their bodies, then the world.

Scripture says God first saves people’s souls or spirits, then their bodies, then the world.

Man says that we as “gods” ourselves can first save our physical world, then our souls by evolving into some kind of spiritoid entities — ignoring the importance of the body.

Last week, commentator D.M. Dutcher called this “transhumanism.” And that’s exactly what it is. Though such beliefs are common to many false religions, the notions we most often see in sci-fi (really they’re fantasy elements disguised as sci-fi) combine classic humanism’s “aren’t humans great” posturing — as seen in many Star Trek episodes — and the “one day we will become energy-based spirit beings” of New Age and “spiritual” religions.

It’s a bait and switch: Yes, humans are great, except for what makes us human.

Now for a more encouraging outlook. Many other stories do honor both the goodness of the physical world underneath the corruption of sin — and more helpfully, honor the idea of a hero who has originated in a higher status and instead deigned to dwell among man.

The most recent example may be the trailer for Man of Steel, the new Superman film series re-launch to release (in the U.S.) on June 14, 2013. If you haven’t seen this trailer, behold.

More than other heroes, Superman is often seen in this pose. I wonder why?

I’m intrigued. It seems the makers are not merely gritty-rebooting Superman. Instead they may be going the direction I’d hoped, not by angst-ifying our hero — which did drag down the otherwise promising Superman Returns in 2006 — but by assuming that he is a truly good man. How would the world see him? Put off by his goodness, would they reject him?

This is an echo of incarnation: a mighty hero becoming mortal, living as one, to save them.

With that as the film’s theme, even if not its main theme, the trailer didn’t even need to jump right into showing “the Christ-figure pose,” as author Jeffrey Overstreet observed.

Why does incarnation truth captivate us? How does it inspire real and imaginative worlds?

1. God-become-man is solidly Scriptural.

Christians are bound to accept that Jesus Christ is both God and man. Too many Scriptures confirm both His human origin and His divine nature. Too many heretics have immediately gone for the doctrinal jugular by challenging Jesus’s true humanity (the Gnostics) or His divine nature (the Arians, and also modern-day cults such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses).

For those who love Christ the Hero, we have no reason to doubt His words about Himself or the testimonies of those who met Him. “In him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily,” the Apostle Paul wrote (Col. 2:9). And we do not accept these words only out of some sense of obligation. If we say we love Him, why would we doubt His self-described origin? Why would we even want to divide His “natures,” or treat Him only as divine or only as a man?

2. God-become-Man means we can see the image of God.

For some reason, occasionally I get into more discussions about what a “graven image” is and whether Christians can, for example, make a movie about Jesus played by a human actor. Recently someone mentioned that a Nativity scene includes a “graven image,” versus the second of the Ten Commandments. To that I responded:

If that’s a “graven image,” so was the Face of Christ, the eternal God made flesh. The fact that Christ was, and remains to this day, a Man with an “image,” must be taken into account.

Some will say, “Well, that was a perfect representation.” Yet even after He was gone, the disciples would have tried to recall His physical “image,” and not recalled it “perfectly.”

[A nativity-scene Jesus is] an imperfect representation, [but] based on the precedent of He Himself being made flesh. One must not make a “graven image” of God [the Father] as He is Spirit and should not be reduced that way. However, Christ was a Man, a real Man, and remains so to this day. God all but invites us to imagine Him immediately and personal, while also reminding us of His power, transcendence, wrath, and mystery. He is all of these.

Don’t worship an image like this one. But Jesus really was the physical “image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15).

It may be because some people, deep down, doubt that Christ was truly human and the very “image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15), that the apostle John (1 John 4:1) told people to test spiritual influences by asking whether they accepted Christ had come in the flesh.

Jesus is both good and heroic, yet appears “flawed.” Just as any good story’s hero. This way He is “accessible.” But there’s a vital difference: Jesus only seemed flawed. He never sinned.

No, I wouldn’t worship a movie-Jesus or a nativity-scene Jesus. I also would not worship a fellow Christian, one who now bears the image of Christ! But if Christ stood before me, I could bow down and fully, unashamedly, and rightfully, with the Creator’s endorsement, gaze upon His Face and worship a Man.

3. Jesus remains God-become-Man to this day.

This is something we may not often speak about, possibly because it hurts our heads. Yet imagine the encouragement, the wonder! Jesus remains the God/Man even now.

Yes, somehow even in the present-day Heaven that could be an incorporeal realm. Even making intercession before the throne of God (Rom. 8:34). Even standing at the Father’s right hand (Acts 7:56). How does He do it? That part we don’t know. Which leads to …

4. Our Hero in the flesh is a Biblically true, God-endorsed mystery.

Pastor and columnist Jared C. Wilson phrased it like this:

When Colossians 2:9 says, “For in him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily,” we know that the fullness of deity dwelled in fertilized ovum.

Will the Empire State Building occupy a doghouse? Will a killer whale fit inside an ant?

And here we are told that omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, utter eternalness and holiness dwelled in a tiny person. This makes Santa coming down a chimney seem a logistical cakewalk.

“The head of all rule and authority” (Col. 2:10) had one of those jelly-necked wobbly baby heads. The government rested on his baby-fatted shoulders (Is. 9:6).

Such a truth strains our corporeal minds. Have you wondered about how this later worked?

- Being fully God, did Jesus keep His omniscience? If so, how could His human mind keep all that knowledge? Or did He choose not to know some things (Matt: 24:46, Luke 2:52, 8: 45-46; or Heb. 5:8)? Was that part of the divine “emptying” (Phil. 2:7)?

- Did Christ choose to “turn on” some divine superpowers, such as watching Nathaniel long-distance (John 2:48), or knowing about the coin in the fish (Matt. 17:27)?

Scripture doesn’t tell us how. It only assures us, through Christ’s example and in later works of doctrine, that Christ was both fully God and fully Man.

Maybe that’s why Christmas over other holidays brings a unique wonder. Make no mistake, Good Friday and Easter matter. Yet only during Christmas do we celebrate the fact that, as Isaiah predicted in Isaiah 7:14, the Hero actually became God-with-us, Emmanuel.

It may not always be energy-based, but yeah, the idea that people can become immortal or as gods drives a lot of science fiction. It’s become an actual philosophical movement too, in the same way that cyberpunk briefly became one from the novels of Gibson and others. A definition of the movement can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transhumanism

I think why incarnation is popular in general is that we understand at a gut level that some things we need a Mediator for. That we can’t really bear the full weight of divine reality without something that can bridge us. This is why Christianity is strong, because you would have to be both fully God and fully man to be able to bridge the gap. Other gods are either people in drag, or are so alien and unknowable that contact with them swallows us and our personality up.