Imagination: For God’s Glory and Others’ Good, Part 5

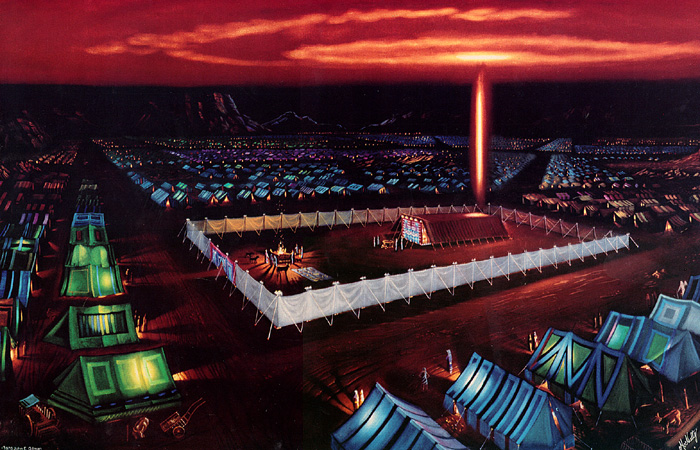

The Tabernacle: only the first clear example of God desiring glory through His people's imaginations.

Some Christians (actual or otherwise) abuse their own imaginations, and no one’s insistence that imagination, like sex, is a good thing will by itself solve their heart corruption.

Others may use their imaginations, yet suspect it would be more “spiritual” to focus only on nonfiction and avoid supposed corruption by imagination. And to resolve that, it takes a Biblically based Theology of Things to show why sanctified imagination can glorify God.

So many examples of God’s people glorifying Him through creativity are found in Scripture, matching perfectly the Bible’s more-direct encouragements to honor Him in all that we do; I suspect a whole book could be written drawing these out.

In this series I’ve explored only a few people, Bezalel (and Oholiab), who used their gifts to honor God with His people; and Daniel, whom God gifted to stay holy and yet also be a light for Him in an abjectly pagan society, even as Daniel studied actual pagan-religion materials. All of these honored God in creativity and vocation, in both “church” and “worldly” settings.

Now we come to the final and best example of imagination for God’s glory. This is so clear a proof that I’m almost sure if we went too far with it, we’d reverse churches’ usual practice and claim that storytelling, more than singing, honors God better.

After all, we could say, Jesus is mentioning singing a hymn once (Matt. 26:30, Mark 14:26), but never is He said to have written a song — and yet He told dozens of stories!

After all, we could say, Jesus is mentioning singing a hymn once (Matt. 26:30, Mark 14:26), but never is He said to have written a song — and yet He told dozens of stories!

I won’t go that far. But it would be an interesting argument-by-logical-conclusion to suggest this to someone who does not see the point in Christian storytelling (or worse, suspects it as equivalent to lying)! Bezalel, Daniel and many other Biblical figures help support the truth that God’s people can honor Him and share His truths in new ways with their God-given imaginations. Yet we only need Christ Himself to prove this!

What can our Savior’s stories show us about storytelling, for God’s glory and others’ good?

I’ll try to address a few points here, but really, this does deserve a book-length treatment …

Were Christ’s parables truly fiction?

The first time I clearly heard "Jesus' parables could not be fiction" was in this book. Of course, its author opposed that notion.

There’s a notion about Jesus’ stories, which I first read about in TED DEKKER’s nonfiction book The Slumber of Christianity. It claims this: Jesus could not tell lies, so one way or the other, His parables must have actually been descriptions of things that really happened.

Were Christ’s parables historical and not fiction? Perhaps they were; surely at least some of them were close enough to His hearers’ realities that they could think, say, about the story of a woman who lost her coin, I know someone like that. Other general comparisons, such as a shepherd going after a lost sheep, or men harvesting grain, surely had real-life parallels.

But elements from several parables seem to show they had to be stories:

- First, the very fact that we’re confused about the parables’ historicity gives credence to the idea that they were fiction. To prevent confusion, why would Jesus have not said (a la sports-movie trailers): Based On a True Story?

- Only in one parable did Christ name one of the chief players, Lazarus, and includes the real-life figure Abraham. And that was in one of the wildest of His parables, with communication between compartments of Sheol and everything (Luke 16: 19-31).

- Shepherds, sowers, or an unjust judge may have been common in Jesus’ day. What about the kings in several of the parables, who are never named? In one such story, Jesus says “the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who …” (Matt. 18:23 and onward, emphasis added), but never names the king or states he was real.

- Several of the figures Jesus mentioned have some very strange fantastical powers, if indeed they were historical! In two parables, found in Matthew 22 and 25, one king, and a man returned from a long journey, both punish people in a way impossible in the real world: they have the villains cast “into the outer darkness.” Whoa. How would a real-life king get access to “the outer darkness”? These are perhaps the clearest examples of Jesus drawing upon “fantasy” to illustrate reality.

Were Christ’s parables only to teach Values?

I’ve been trying to find written support for the idea that parables must be real, but it seems sparse. One online site I did find was this one, in which the writer doesn’t so much condemn stories as express his own nervousness about them. (When he says that reading Jurassic Park made him wonder if it was real, I suggest he might need to avoid fiction, but others need not do this.) Yet when he mentions a purpose of fiction, I have a more-vital question …

We tell fiction to entertain, and sometimes (more often in the past) to carry a moral, to train people in virtuous character. Morality is good, but does the end justify the means?

Goofiness like turning Gideon into a high-school band player is okay, only if it's also "A Lesson in Trusting God."

This perception is frequent: fiction is only either entertaining or meant to show a Moral Point. Of course, many Christian stories try to do both. VeggieTales DVDS, for example, have on their covers bright colors and fun characters, but also assurances for Parents and Legal Guardians that this story gives “A Lesson in [Moral Behavior].” In effect this is an attempt to “make up” for being fun and entertaining by also teaching a Value — a kind of penance.

But where did the entertainment-or-Value clash come from in the first place?

Was that Jesus’ purpose in telling parables — only to give entertainment or to Moralize?

Either excess breaks down when one considers Christ’s true purpose: not merely to repeat the Law and Prophets, but to fulfill them (Matt. 5: 17-20) and proclaim “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15). Moreover, earlier in Luke 16, before His fantastic story set in the afterlife, Christ tells about a dishonest manager. His account is meant to restate His point that even His disciples can learn from the businessman’s foresight and preparation for the future, though without using his methods.

Not all actions described in Christ’s parables are moral. He didn’t mean them to be. Rather, He used any story elements from allegory, reality, or even fantasy, to support His mission: to fulfill the Law and the Prophets, and to call others to “repent and believe in the Gospel.”

Jesus: the ultimate storyteller, beyond only allegories

Here’s another belief I used to hold about parables: they are all allegories. Maybe this belief gives rise to the notion, often well-meaningly applied to praise C.S. Lewis’s fiction or to oppose other non-allegorical stories, that if we do tell stories, they must be Allegorical.

But is it true that every one of Christ’s parable is a direct Allegory, which includes specific parallels between figures and objects in the story to spiritual meanings in real life?

I'm indebted to "How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth," which I recommend even if only for the chapter on reading the parables and the "allegory-only" belief.

Many Christians might bring up Mark 4: 1-20. Here, Jesus does tell a direct-allegory story — the parable of the sower — then seems to say all parables will be like this, then draws out the meanings only for His disciples. So all His stories must have secret meanings, they say.

Others, though, portray Christ’s parables as only intended as a sort of populist presentation, a way to reach the people in their language and make His truth memorable.

I see no reason why His purpose can’t be both. In fact, Scripture supports both. Christ told at least two kinds of parables: either closed-captioned for His disciples only (as in Mark 4: 10-12) or to make a point for a broader audience (as in Matthew 21: 33-46). This may also have applications for Christian storytellers today: we can tell stories for both “sets.”

But if Christ’s parables were only allegorical, what do we make of His story about a dishonest and shrewd manager (Luke 16), or His very short story about man who sells all he has to buy a field with treasure (Matt. 13:44)? If we tried to force them to be pure allegories, we might conclude that God’s Kingdom could conceivably be built with shrewd and dishonest business practices, or even that we earn salvation. But that’s not the genre or intent of those parables.

When Jesus explained to His disciples the sower parable’s meaning, He never claimed all parables would be direct allegory. Instead we find that He constantly varied His style:

- Sometimes He explained allegory parables’ meanings. Other times we don’t see this.

- Stories that begin with “the kingdom of heaven is like …” do not mean you need to listen to the story and find which Thing represents the Kingdom. Rather, His term “like …” applies to the thrust of the entire story. This can be seen in Matthew 13 alone, in which He tells about a man seeking treasure, in which the treasure could seem to represent the Kingdom, but then says “the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearls” (verse 45). Here, the Kingdom is not the merchant. Instead the Kingdom is shown in the whole story: the worth of the things sought.

- Some of His parables contained meanings that were closed-captioned for His disciples. Others were targeted to nonbelievers, as in Matt. 21: 45: “When the chief priests and the Pharisees heard his parables, they perceived that he was speaking about them.” Often He would vary his approach based on His audience at the time.

- Sometimes Christ would ask openly “What do you think?” Then, oddly enough, He would go on to say exactly what His point was (as seen in Matt. 18:12 and onward).

- Christ told similar stories with different points, such as two version of the lost sheep (such as Matt. 18: 10-14, about straying believers, and Luke 15: 1-7, about a shepherd pursuing a stray nonbeliever). Again, He varied the story, based on His audience.

- Jesus used fantastical elements in at least two stories, mentioned before, in Matt. 22 and Matt. 25, about leaders who punished the wicked with “outer darkness.”

That last leads to one finding that seems startling on the surface: In many of Christ’s parables’ “story-worlds,” God Himself is never mentioned as existing! In fact, many of Jesus’ stories presume God’s “absence,” yet in service to the real world in which God, His truths and Kingdom and Gospel, are unavoidable.

What applications, I ask, might that have for Christian storytellers today?

Might this also gives us Scriptural support to write parables or stories in which God is not shown as a key player, but which illustrate truth about Him and His Kingdom anyway?

What else might you have found in Christ’s parables, which has helped you as a reader or even writer of visionary fiction, or even other genres? Something I missed here, perhaps? Another element that needs to be clarified, so that I’m not making my own stories about His stories, and so that I can add to that Jesus’-parables-and-fiction book I’ve already started?

God can be glorified in imagination. Jesus Himself did this, and blessed others by helping them grasp His Kingdom truths. His people, for His Kingdom, can do the same with all his good gifts — echoing His old truths in new ways, in many genres, even the fantastic ones!

One of my favorite authors, Bryan Davis, said “A fantasy story is something that can’t happen without a miracle.” A good defination, and a good guideline too…

This idea that fiction must either entertain or convey a Moral leaves me asking the same question as Professor Kirke: “Bless me, what do they teach them at these schools?” Going back to Chaucer and Sidney, and possibly even (yes) to Plato, in situations where fiction per se is being condemned, one of the standard justifications is that it both entertains and conveys Truth. Chaucer put it as “sentence and solace” (which just shows how much the language has changed since then), while Sidney said that the two purposes of “Poetry” are to “Teach and Delight.” If fiction utterly fails in either purpose, the condemnation of the endeavor holds: empty delight is (at least arguably) worthless, and a story with a Moral that isn’t the slightest bit entertaining would have worked far better as an undisguised sermon.

To quote a previous post in Speculative Faith:

And Jesus made fantasy stories come true. He made a coin appear in the mouth of a fish. A fig tree withered at His command. He calmed a storm with a spoken word. He walked on water. Without His power, none of these events could ever occur. They are fantasy stories brought to life. And each one taught us a lesson we will never forget. Why? Because fantasy brands images on our minds that cannot be erased.

Bryan Davis, “Why Fantasy,” part 1, Aug 23, 2006. http://www.speculativefaith.lorehaven.com/2006/08/23/why-fantasy-part-1/

“In two parables, found in Matthew 22 and 25, one king, and a man returned from a long journey, both punish people in a way impossible in the real world: they have the villains cast “into the outer darkness.””

Unless Jesus is referring to Himself/God the Father. For example, Matthew 22:1-14 seems like a summary of the entire Bible up until that point…and the wedding banquet also seems to fit together with Revelation 19:7-9. Another thought: a while back, I heard a Bible study that drew connections between the “outer darkness” verses and the Millennial kingdom/temple found in the latter chapters of Ezekiel…which was interesting.

MGalloway, thanks much for your comment.

I fully agree that Christ using the wealthy man, or the King, as allegorical stand-ins for the Father is very likely, given the nature of the punishment and the use of a power only God could have in reality — the right to send someone to “outer darkness.”

If so, this indeed confirms the parable is a story, fiction used to point to a real-life truth, and not a description of an actual event. I’m quite sure many of Jesus’ parables contained allegories, as real life often does (another Biblical example: marriage as an allegory of Christ and His Church, Ephesians 5). Yet it’s clear that He was not merely describing literal events that happened in some place only He knew.

Okay, but how about verses 3-5? Verse 3 (NKJV): “…and sent out his servants to call those who were invited to the wedding; and they were not willing to come.” And then in verses 5 and 6, it states: “But they made light of it and went their ways, one to his own farm, another to his business. And the rest seized his servants, treated them spitefully, and killed them.”

Reading these verses, it seems that the “they” refers to the Israelites, and the servants (at least in these early verses) refers to the prophets that were sent to them. Verse 7 could be a reference to the destruction of Jerusalem (in 586 B.C.), and verse 9 could be a reference to things being opened up to the Gentiles and perhaps is even inclusive of our own current times. Verses 10 through 14 seem to be speaking of the future, however.

Good discussion here, by the way…and on a challenging topic, too.

Well, as far as Dekker goes, I don’t think he was implying in any way that those stories all had to be real stories, just that they could’ve been. Either way, the larger point is that Jesus used storytelling as a teaching tool, just like people have for thousands of years; and the bigger point is what he was trying to communicate in each of them.

As far as prophecy goes, all I’m going to say is that I tend to think many of those passages have dual meanings: a more immediate one with a future parallel. Once upon a time I had a whole argument for that, but that was…probably a decade ago.

Perhaps I’m missing something, simply because I think it’s clear from the parable that it is both a story and includes allegorical elements that echo aspects of God’s story.

In Matthew 22, after all, Christ begins with “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to …” establishing from the start that this next will contain allegories. “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to …” simplifies things for us a lot! What follows will be something with which we may compare the Kingdom of Heaven, i.e., Christ’s Church, destined for a remade, restored physical/spiritual universe. And comparing the wedding here with the imagery of the New Jerusalem and the Church as Christ’s bride would seem only apt, especially given the real-yet-with-allegory meaning of marriage, the mystery more fully revealed in Ephesians 5.

More from MGalloway:

It very well could be! Yet I agree with Kaci that “many of those passages have dual meanings: a more immediate one with a future parallel.” Some Christians, after all, see a dual meaning in Daniel’s prophecies that were most clearly and quickly fulfilled by the madman Antiochus “Epiphanes” — but those prophecies suddenly jump into a much higher scale and seem to be talking about an even worse, and possibly future, dictator. And prophecies about Christ’s coming typically blend His first arrival, as the suffering servant to fulfill the Law and the Prophets, with His second coming, as a conquering King to destroy all God’s enemies and bring perfect peace on a New Earth.

Perhaps that is why, for some parables, Jesus did not directly explain their meaning as if this is The Set Meaning and there isn’t any other. Fiction operates on so many levels, and for fiction told by a Savior Who could very likely foresee many types of allegories imbued in the tale, it’s not a stretch to consider He had in mind more than one meaning.

What we can’t do, of course, is come up with a possible meaning contrary to what Scripture more directly reveals about God and His Gospel.

Verse 7 could be. Or it could represent, more generally, God’s destruction of the wicked — those who refuse without repentance His generous offer to attend His “feast.”

Given Christ’s emphasis on restoring Israel’s role as being a light to the nations, a “kingdom of priests” (a theme that also recurs in Hebrews) as God originally intended, I have no doubt verse 9 was at least a reference to the Jews-to-Gentiles theme. And yet one could certainly also apply this meaning to countless recurrences of similar scenarios: when those who once professed to be God’s people “fell away” (i.e., never really were) and were replaced by another people, or a generation, who proves faithful.

Could be — yet in some sense Christians believe that is being fulfilled every time a person dies having still rejected repentance and faith in Christ right until the very end.

Thanks much! These are the roots, I think, of a more-challenging pursuit I hope to undertake soon: overviewing all Christ’s parables, or most of them, with the foundation that God has always been telling “stories” about His big Story, ever since the Old Testament, and drawing out specific applications for visionary storytellers today.

Good points by both you and Kaci…and I do agree about how Jesus used various situations to explain larger truths.

I think the issue for some, however, may be the use of the word “fiction”, because that word has somewhat of a loaded meaning. In other words, people tend to equate that with things like Batman, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, etc. Likewise, when you wrote:

“These are perhaps the clearest examples of Jesus drawing upon “fantasy” to illustrate reality.”

…could potentially lead to a sort of “slippery slope” situation where the reader starts to wonder what other parts of the Bible use “fantasy” or fictional elements. Maybe I’m wrong on that, I don’t know.

Along with this, there is already the issue for some with the Book of Jonah…where some Christians have called it outright fiction. Usually the logic is…”well, how could anyone survive in a whale for three days?” Yet Jesus referred back to Jonah (and ultimately connected it to himself). Later on, too, a prophecy of Nineveh’s destruction came through Nahum…and maybe in some subtle ways the two books together echo Christ’s first and second comings to some limited extent.

But if we call the Book of Jonah fiction, does that make Nahum fiction too? What about the ruins of Nineveh that still exist? Then there’s this curious line about Jesus in Luke 24:27 (NKJV):

“And beginning at Moses and all the Prophets, He expounded to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning Himself.”

E. Stephen Burnett wrote:

“These are the roots, I think, of a more-challenging pursuit I hope to undertake soon: overviewing all Christ’s parables, or most of them, with the foundation that God has always been telling “stories” about His big Story, ever since the Old Testament, and drawing out specific applications for visionary storytellers today.”

Sounds interesting!

I’m actually one of those some people, to be honest. I don’t think it’s good to use the same terminology (characters, stories) for Scripture that we do with fiction, just because it creates a subtle shift. I’ve picked on Stephen a bit. 😛 It’s also why I don’t really like saying things like “Well, there’s violence in the Bible.” That’s comparing Lord of the Rings with a book of the History of the British Islands. Sure, there’s violence in history books, but that doesn’t mean it’s okay to use violence in fiction.

As far as Jesus’ stories go, I don’t see a problem with saying that when Jesus referred directly to historical figures (Jonah, Moses, Nahum, Abraham, Isaiah), clearly those were real stories while things like the prodigal son may have been real, but might have been fictitious, too.

And even all that said, we could probably have a lively discussion on the different literary genres present in Scripture.

MGalloway, that’s why I want to be very careful about this issue, given some misunderstandings about the Bible — ones that I’ve held myself, as a practitioner of what I recently heard called “folk theology,” simple and cute, and occasionally Biblical, beliefs!

Like Kaci said just above, the issue is one of the Bible’s different literary genres. God as the author, “breathing” His Word, was a genius and didn’t simply string together a bunch of proverbs and pieces of religious advice (e.g., the Qu’ran). He inspired varying genres throughout the 66 books of the one Book, from historical narrative, to direct Law, to books of songs/Psalms, proverbs, philosophical treatises, prophecies, Gospel narratives, more history, epistles, and just-plain-weird/prophecy/thing (Revelation).

All of these have varying guidelines for literal reading, and I’m still working through those (thanks to books like How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth). For instance, some will say “you must keep your adult daughters at home until they’re married,” and point to the account of Rebecca and say “this is the literal understanding.” No it’s not. That passage doesn’t prescribe marriage, but describes it in that instance. The main meaning behind that account is the history of God’s dealing with His chosen people.

Conversely, someone may say (I may get in trouble here) “we must interpret the words of Genesis 1-2 as metaphorical.” But that passage, though I understand it also carries poetic connotations, would never have been understood other than as describing history. (Side note: people may say “Genesis’ creation account is poetic,” as if proving that automatically disqualifies it as also portraying a claimed literal history!)

That seems the key difference: Christ referred to Jonah, just as He referred to Adam and Eve, as a real person. He never referred to His parables that way. By giving the key words “A certain man …” or “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to …” it’s clear He is beginning a story, a tale, clear even to we readers who weren’t there to see His change in tone or posture, or perhaps hear a natural break in His voice.

We agree on this, Kaci. I’ve tried to cut terms like “story” out of my descriptions of Biblical elements, replacing them with the word account. (In fact, just now I changed the word above!) And character does not seem a good term to use for, say, Adam, Eve, Jonah, or especially Christ, all of whom were real people from history. After all, no one says “in the story of the Civil War, the character of Abraham Lincoln …” etc.

However, the parables are different. I’ve no problem with terming them “fiction” or “stories,” with “characters,” because Jesus Himself was clearly telling stories about characters to illustrate very real points about Himself, the Gospel, and the Kingdom.

I’m going to have to remember the phrase ‘folk theology.’ It’s a great one.

I just remembered being bugged by your previous use of ‘imagination’ on largely the same logic. It really could just be me (cuz, y’know, I”m weird). Anyway, I know, but since it came up recently I just used it. 😛

Right.