If It’s Fiction . . .

The CSFF Blog Tour is featuring Rebels by Jill Williamson, the third book in her dystopian Safe Lands trilogy. I’ve not read a lot of books in this niche of speculative fiction, but I admit, I was thoroughly captivated.

The CSFF Blog Tour is featuring Rebels by Jill Williamson, the third book in her dystopian Safe Lands trilogy. I’ve not read a lot of books in this niche of speculative fiction, but I admit, I was thoroughly captivated.

I think one of the most important aspects of futuristic novels is to establish a believable world, so one of the first things a writer would have to consider is, What might the world look like a hundred years from now, or two hundred, or five hundred?

I know some people don’t want to read futuristic stories—science fiction or various types of fantasy set in the future—because they believe Jesus Christ’s return is imminent and there will be no dystopian world or space travel or post-apocalyptic future.

It seems to me that this approach to fiction is needlessly limiting. All novels are make-believe.

Writers imagine and create a world based on what they think it would be like to be Eve after she and Adam have been removed from the Garden of Eden or an Englishman traveling via ley lines to different places in different times or a Swiss national during World War II or a Dalit caste member in India during the mid-twentieth century or a contemporary homicide detective who’s fallen out of favor with his commander or a twenty-first century mom who’s decided vaccinating her children may cause them harm.

Still other writers imagine what the world would be like if elves existed or if animals could talk or if there were life in space, more advanced than ours.

I grew up with books about trains that thought they could, and toads that went on wild rides, and rabbits that out-maneuvered bears, or foxes that plotted how to escape the local farm hound.

Imagination. Pretend. Make-believe. That’s what I discovered inside books. And yet, there was also truth. The pig who built his house of bricks was wiser than those who built using straw or sticks. In the end, wicked step-sisters didn’t profit by their wickedness, and the prideful emperor was foolish for walking around without any clothes.

What, then, is different about a story set on Mars in 2237 when earth has built colonies there? Or set on earth in 2183 after most of the population has been wiped out by a pandemic? These utilize the same principle as other stories—make-believe.

Truth in stories is a tricky thing. On the story-telling level, often referred to as realism, readers need to believe in what’s taking place. When they accept the “what if” premise—what if Alice fell down a hole into a strange land with talking beasts and other strange phenomena—the events that follow should be believable. In addition, the characters should act in a way that is consistent with the motives and personality traits the author has given them.

Truth in stories is a tricky thing. On the story-telling level, often referred to as realism, readers need to believe in what’s taking place. When they accept the “what if” premise—what if Alice fell down a hole into a strange land with talking beasts and other strange phenomena—the events that follow should be believable. In addition, the characters should act in a way that is consistent with the motives and personality traits the author has given them.

In addition, there needs to be internal consistency. If the story is set in a real place and time, then it should adhere to the known truths of that location and age. If it takes place in a fanciful location or time—Oz or Wonderland or Deep Space Nine or Perelandra—the rules of that world should become clear and should have coherence.

There’s a second level of truth, however. Stories need to tell the truth about the way the world works, either in the physical realm or in the spiritual or both. Consequently, a story should accurately reflect humankind’s nature, the existence of good and of evil, a person’s search for purpose or belonging, the truth that life is precious and has meaning, that God exists and rules over all, or any number of other eternal, universal truths.

My guess is, readers who don’t believe Christians should write or read dystopian fiction or science fiction set in the distant future, do not understand the nature of fiction. Some, at least, want to limit stories to that which could happen. Consequently, since animals could not talk, stories should not be about talking animals. Since toys could not animate, stories should not be about animated toys. Since (in their thinking) Christ will come back before some far distant time, stories in a far distant time could not happen.

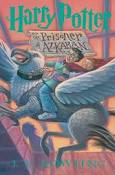

As I think about speculative stories, I realize what a double-whammy the Harry Potter books endured. First were readers who thought writing about wizards and witches was sinful because of the Bible’s condemnation of divination and spiritism and sorcery. When the Harry Potter apologists pointed out that the witches and wizards were pretend and not intended to reflect actual belief in wizardry, they came up against those who expected fiction only to express that which could happen.

As I think about speculative stories, I realize what a double-whammy the Harry Potter books endured. First were readers who thought writing about wizards and witches was sinful because of the Bible’s condemnation of divination and spiritism and sorcery. When the Harry Potter apologists pointed out that the witches and wizards were pretend and not intended to reflect actual belief in wizardry, they came up against those who expected fiction only to express that which could happen.

Stories can be sinful from my perspective—they can lie about God or about the way our world works (that life is meaningless, for example, or that evil wins in the end). They can also fail on the story-telling level. But I don’t see a way that an entire genre could be written off as “untruthful.” An understanding of what fiction really is would challenge such a position.

Thanks for this, Becky. I agree with everything you said. Sometimes, I think we all need to relax and spend some time at the Mad Hatter’s tea party. HA!