Five Myths Of Cultural Engagement

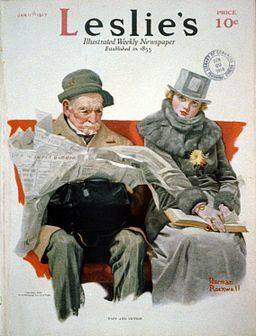

“Fact and Fiction”. Color halftone reproduction of painting by American painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), used as cover illustration for “Leslie’s illustrated weekly newspaper”, vol. 124, no. 3201, 11 January 1917.

In the world, but not of the world. Christians have debated the application of that concept for a long time. As Jesus states in John 17:15-16 . . .

I pray not that thou shouldest take them out of the world, but that thou shouldest keep them from the evil. 16 They are not of the world, even as I am not of the world.

We are called to be a light to the world, which denotes engagement with it, but not of the world, which indicates being one with it.

On one side are those who call for total separation from the world. Holiness demands separation for fear of contamination. On the other, people will point to verses indicating we are to be witnesses, and we can’t do that without engaging on some level. After all, Jesus ate with sinners, visited their houses. Separation for Him obviously didn’t mean not to befriend them, to not engage them on their own turf.

When we throw Christian speculative fiction into the mix, it becomes even murkier, because we’re no longer talking only about real life, but a fictional world and characters that are perhaps not Christian. The line between being in and not of can seem fuzzier, and where that line is drawn for any one author or reader can vary greatly. Much of our discussions center on this topic in one way or another.

So in my never-ending quest for truth, justice, and the Kingdom way, I offer the following myths of cultural engagement in Christian fiction, in no particular order, for your consumption and consideration.

The Author is God

This happens when the author is expected to have infallible powers in constructing their fictional world so that no theological contradictions exist. Some are prone to classify an author as of the world because they perceive a theological error, by their estimation, reflects the author’s belief.

Truth is, while God is all knowing and created His world perfectly right the first time, no author will catch all world-building conflicts within their work, much less their own theology. Throw in the reader’s theology, which is guaranteed not to match the author’s completely, you have an impossible task to duplicate on paper what God did in our world. Readers should expect not all dots are going to connect.

Stories Must Contain Bible Quotes, Prayers, and/or a Gospel Presentation

Not that those are to be avoided, but there are more ways to shine the light of God into the world than those. Sometimes the most effective way to attract people is with honey instead of a fly swatter.

Not all stories serve the same purpose or intend to reach the same audience. Jesus changed His approach for each individual, just as Paul spoke to the Athenians differently than he did the Ephesians. Using a one-size-fits-all spotlight approach will work for some but send others packing. We’re called to be more like Paul in seeking out as many as possible.

I am made all things to all men, that I might by all means save some. (1Cor 9:22b)

We Are Called to Shine the Black-light of the Gospel

In an attempt to witness to the sinner, we seek to establish some identification between them and our characters. All well and good, but some attempt to do this by unscrewing the light bulb and putting in a black-light. Too much of that, and there isn’t much light left shinning to make a dent in their darkness.

More important than having a story non-Christians can identify with is having one they can respect. Hiding the light might not make them run away, but it won’t draw them either. The goal is to make an authentic story for that audience where identifying with and challenging their world views happen together.

We Must Avoid Any Idealized Characters

The idea is no one can relate to a “perfect” Christian. Granted, some books produce a caricature rather than an authentic person, which is bad, but many secular books have such people.

In the hero’s journey, you often have the mentor/teacher role model. Whether Yoda from Star Wars or Faramir from Lord of the Rings, many books have that person we look up to, even as we know we might not be that good. We innately long for true heroes.

Having a cast of flawed characters with no heroes of inner strength and morals will sabotage an authentic story as surely as a cast of righteous caricatures.

Everything About God Needs to be Allegorized

Often this is done by giving God and Jesus alternate names in the story’s world. The most popular example is Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis.

While there is nothing wrong in doing this, don’t expect this to get God and Jesus into the story under the radar. Few will be fooled. May even perceive it as offensive in some cases. The direct approach, placed in real-life situations, can be more honest and effective many times.

To summarize, stories that engage culture to influence it while not being influenced by it are those that garner respect and authenticity by not merely pointing out the darkness, but effectively shine God’s light into the darkness. On either end you have the extremes: total separation from the world so it is no longer in it, and complete identification with the world that we become a part of it. Neither extreme ends up being a light in the darkness. One hides it under a bushel, the other under their thorns.

What other myths are you aware of?

“Often this is done by giving God and Jesus alternate names in the story’s world. The most popular example is Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis.”

I was encouraged to do the same thing in my fantasy novel by an editor from Scholastic because, well, it’s fantasy. And I’ve included characters and fairies that aren’t in the Bible. I’ve seen it done in other fantasy novels, as well. But Bryan Davis doesn’t do that in his Dragons in Our Midst books. He’s right up front. He’s bold. There’s no mistaking it. And I’m not put off by it at all.

I think it comes down to this: what does your story require?

Bryan Davis’s books are set in the “real” world, that is, our Earth. Fantasy stories not set on Earth or set in some alternate reality just sound silly when they use the “real” names. Every culture has had it’s name for God; why should a fantasy culture be different? While Lewis changed Jesus’ name and form for the Chronicles, he kept Father Christmas … something that almost brought him and Tolkien to blows, because Tollers believed that something as distinctly Earth should not be in a foreign world. Lewis went on to retcon that notion by having the first king and queen of Narnia be an English human couple, but that doesn’t necessarily explain the presence of all of his other Greek gods, etc. (Indeed, the connection is not made in the Narnia series, but in Perelandra, where Ransom muses that perhaps all of the things that are mythical in our world are actually inhabitants of other worlds.) The needs of the story dictate. I remember being really thrown by the name of Jesus in such stories as the Trophy Chase trilogy and the Annals of Lystra; it seemed jarring and Western rather than True, if that makes any sense.

It does make sense – thanks

Ted Dekker’s Circle series has Elyon–which is actually a Biblical name for God, just rarely used. And given the over-lapping worlds, it makes sense.

Very nice, balanced analysis. Engaging the world with a story that offers hope in this culture can have such an impact if we know how to talk about it through the lens of the kingdom. Talking about the positive aspects of a story garners so much more interaction than criticizing where we don’t find it perfectly “Christian.”

Cultural engagement is itself a myth (myth as in, a widely held belief that is false). Christians don’t operate outside culture, so engaging it or re-engaging it becomes an artificial exercise. Regarding the other definition of myth, that is what storytellers actually engage in. Storytellers are mythmakers to one extent or another. And, by the way, I love the myth about the mentor/teacher. I just wish there were people like that in the real world. No, I know there are for other people. But I want a mentor for ME. I’ve been waiting for so long that now I suppose I’m old enough to be one. Oh, well. 🙂

True to an extent, Jill. I think what tends to happen is we live inside a Christian culture bubble, and the task is always how can Christians engage the more secular culture in a positive way. How to operate in it without being off it. Or do we hide in our safe Christian culture and not worry about engaging the secular? That’s what I’m driving at.

I both agree/disagree with Jill, as is my wont.

Yes, many Christians must pop their own bubble and, at least for a time, practice “cultural engagement” with all the rest of their human neighbors. So for a time, at least, we must think of “cultural engagement” as something we’re not accustomed to doing.

But no, “cultural engagement” is not ordinarily some separate activity. “Cultural engagement” is simply being human. And humans by definition make culture.