Fantasy And Overt Christianity

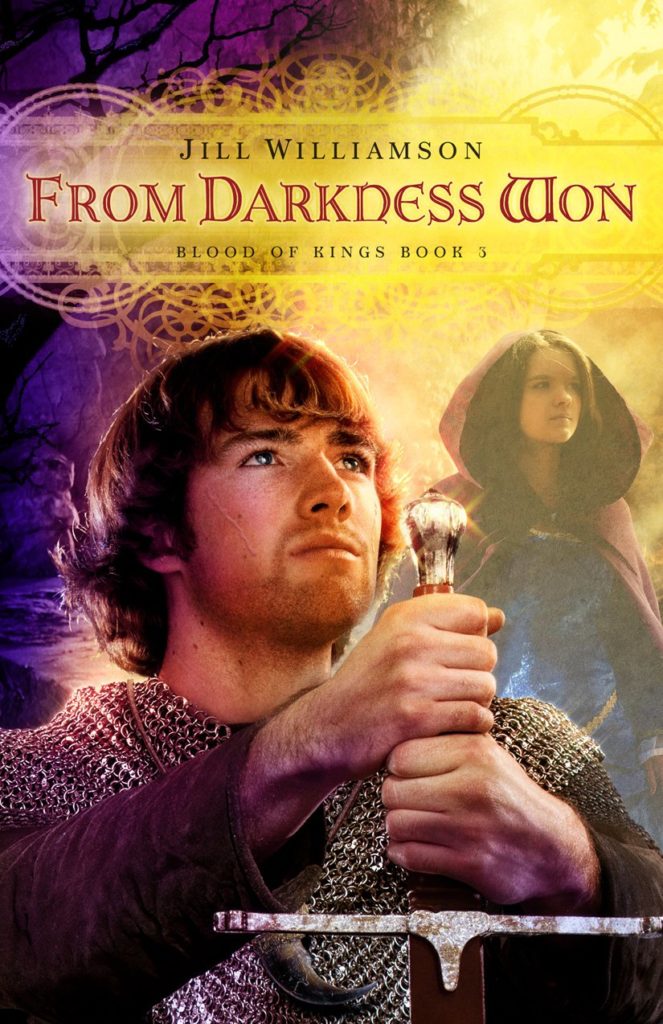

I just finished Jill Williamson’s From Darkness Won, book 3 of her epic fantasy series, Blood of Kings, and noted once again how overt the Christianity is. Some might even say preachy. In fact they have in their Amazon reviews.

Of note, a good many other reviewers who apparently agree with the worldview of the author and main characters didn’t find the stories preachy in a negative way.

Nevertheless, there were those that said things like the following:

- it bludgeons you with the faith

- preaching incessantly and without subtlety

- Occasionally, the Christianity approached preaching

- I was getting irritated by the constant preaching

Jill’s work is not alone when it comes to a clear depiction of Christianity in her fantasy. A friend of mine completed a recent release and remarked how surprised she was to find blatant Christianity in that story.

That got me to thinking about the various other books I’ve read that take place in a fantasy world but show the One True God — identified by various different names. Many also have His Son and/or scriptures that can be equated to the Bible. Here are ones that came quickly to mind:

- The Guardian King series by Karen Hancock

- The Sword of Lyric series by Sharon Hinck

- The DragonKeeper Chronicles and the Chiril Chronicles by Donita Paul

- The Door Within trilogy by Wayne Thomas Batson

- The Binding of the Blade series by L. B. Graham

I’m sure there are others.

The presence of Christianity in fantasy, though couched in otherworldly terminology, seems to upset non-Christians. Is this because the Christianity is transparent or because it is heavy handed?

Which brings up my real question, playing off John Otte’s recent posts — is Christian fiction really just for Christians?

The fact is, we live in a day when Christianity seems to be meeting more resistance in the West than it has for some time. Consequently more readers seem irritated with mention of Arman or Wulder or Eidon — fantasy depictions of the One True God.

Does that mean, then, that Christian writers should refrain from having their characters do what Christians do — turn to Christ, pray for help, give spiritual counsel, worship with other believers, and so on?

If Christians do want to show their characters acting like Christians, should their books then be confined to Christian circles? Should we indeed write for and market to Christians only?

On the other hand, must writers such as R. J. Anderson who publishes with a general market house limit their depiction of Christianity to oblique references, vague symbology, or typology?

In other words, is there no room for a fantasy version of Peace Like a River? In case you haven’t read that story by Leif Enger, the characters believe in God — in particular, in a miracle-working God. Yet the story, published by a general market publisher, was “hailed as one of the year’s [2002] top five novels by Time, and selected as one of the best books of the year by nearly all major newspapers.” It became a national bestseller, despite the clear belief in God.

But that was 2002. Have things changes so much in the last ten years that an overt fantasy about Christianity can only be considered a story for Christians?

What does it take for readers to care about a story even if their worldview might be different from the one espoused by the main character? I have some ideas, but I’d first really like to hear what you all think.

It’s interesting that you should mention Peace Like A River, because the author actually came and spoke at my college . His book featured a father walking on air, mirculous provision, and other elements I can’t quite rember. Maybe one reason he “got away with it” is because the narrator was a young boy, and thus “less reliable”

Interesting point, Galadriel, that the young narrator might make religious themes acceptable. Except I was also thinking about Gilead. I haven’t read that one but understand it is father writing letters to his son — including his faith struggles, I believe. The man may even have been a pastor.

The point is, it also was highly acclaimed. In that instance, though, I can see questioning faith and not coming to a “one way to God, through Christ His Son” conclusion as acceptable in the eyes of … pretty much anyone other than atheists. Because generally people believe in something. So if your something is God and yet you don’t impinge on my belief in something else, then fine, you can have your God.

I think it’s the exclusive nature of the claims of Christ that people don’t like.

Becky

I think a speculative author has to just write what is on his or her heart, the story they feel God has given them, and leave the audience up to Him.

One of the things I’ve learned in my writer’s journey thus far is that, no matter what you write, no matter how subtle or explicit, there will be some who will find it too preachy or too Christian. To use one of my own books as an example: A Star Curiously Singing is very subtle (at least, I thought) in its Christian message. It takes place in a furture where Christianity is all but extinct, so how could it be any other way? Yes, there is a form of religousity represented, and a discussion of alternative belief systems, but the Gospel isn’t presented in that book at all. In fact, there is no mention of Jesus or the Bible. Yet, if you were to look at the reviews, you would still find people that call it “fundementalist Christian propoganda”.

To me, that means one of two things:

1) Some people are so hyper-sensitive to Christianity (and typically it is ONLY Christianity that they are sensitive to) that there is no way you can even present something that smells like Chrisitianity without them being offended, or 2) God is using even the tiniest mentions of his Plan to work in the hearts of the lost, and they don’t like it! It makes them uncomfortable!

Either way, there is little to be done about it. There is no pleasing the first case, and no stopping the second. (And who would want to?)

So again, write what you want. Let God find the audience. 😉

Kerry, I think you make an excellent point — we are not going to please all the people. I guess I’d rather have my work slammed for being too Christian than that it is pointless.

Rick also mentioned the expectations of Christians, so it does seem as if we have the two extremes — those hypersensitive to Christianity in a negative way and those hypersensitive to specific doctrinal requirements.

I don’t want to see our cultural climate chase Christian writers under a rock. I think we need stories that point to Christ openly. I actually liked George Bryan Polivka’s (The Trophy Chase trilogy and Blaggard’s Moon) approach. In his fantasy world, God was still God. He didn’t use an allegorical name for God or hedge on Biblical Christianity. In spite of this, the PW review said the spirituality was “palatable.”

But that was at least six years ago, so would it still be considered palatable today? I wonder.

Becky

Interesting post because I faced this with my Saga of Davi Rhii space opera series and now with my Dawning Age fantasy series. Some objected to my use of real religion, especially since I showed the character wrestling with what that new belief system meant compared to what he was used to. Others had no issue. Paul Goat Allen listed the first book as Honorable Mention on his B&N Book Club’s Years Best SF Releases for 2011, with no mention of it. Others said they never finished. Most gave good reviews. I toned down a bit in book 2 to reflect concern I was chasing off some of my audience. I never intended to preach or convict anyone. I used atheist and agnostic beta readers on book 1 just for that reason. They didn’t feel it was preachy. But I am telling a story of ideological bigotry and felt real religions would make it more powerful. At the same time, yes, we face a lot of resistance to Christianity these days in the west. There’s a lot of stereotyping and intolerance of it. But I also shy away from much CBA literature because too much of it is preachy. Much also can be filled with white washed characters who don’t reflect the real world as I’ve experienced it, even amongst Christians. I’ve served as a missionary and worship pastor for 12 years until recently. I’ve also worked in professional entertainment in Hollywood filmmaking, so I’ve seen a lot of the world and different sides. I think it’s okay to represent our faith and to include the themes in our work. I think it’s not okay to beat people over the head with it. That is not effective evangelism and does the church and cause more harm than good.

Dear Becky,

I think Jonathan Cordero’s article about the CBA having a different aesthetic is the only rational way to go about things – unless you’re like me, and agree with the book burners. Seriously, though, I think part of it is the preachiness, but there is definitely a prejudice. It even extends to ex-evangelicals who write about evangelicalism. A lot of people get down on James Baldwin for all the “God talk” in his novels, even though many of these works are considered by critics to be among the greatest novels of the twentieth century – and Baldwin, being a gay African-American ex-evangelical, was not popular with anyone based solely on his identity. He had to earn his credentials. People actually did criticize Enger, if you look at some of the Amazon reviews. I think what saves Enger – and I hesitate to say this for fear of offending any Reformed people on the blog – is that he did not use his own spiritual tradition (Reformed Calvinism), but drew from traditions with richer internal mythologies, particularly Pentecostalism. Practically every sympathetic take on modern evangelicalism I’ve seen has either depicted Pentecostals (The Apostle, Peace Like a River) or premillenial Dispensationalists, like the movie The Rapture (I wouldn’t suggest watching it, though) and We All Fall Down (I wouldn’t suggest reading it).

Christian fiction is undoubtedly didactic. Indeed, much ex-Christian fiction is as well. I think there’s a lot of similarity between Christian fiction and literary movements like Socialist Realism, which sought to impose one particular reading methodology on a culture.

Good post, Becky.

John, I haven’t read Cordero’s article, but I’m curious why you think we should conclude that Christian fiction ought to have a different aesthetic. As I may have said here before, I think Christians frequently sacrifice beauty for the sake of truth, but I think we should be frank about the fact that that’s what we’re doing.

I still think the most God-glorifying story would be the one that marries truth and beauty.

I think you have a point about Enger. First, if he did receive criticism — and I trust that you’ve done your homework and that there are people who dinged his work because it was about a person who believes in God — that indicates there are people who hate on Christians for the sake of Christ. I mean, Enger received such wide critical acclaim, no one can say those who rated it badly saw poor craftsmanship.

Second, I think perhaps Enger’s “brand” of Christianity did make his story more acceptable. I haven’t done the comparative reading you’ve done to know what branch of Christianity characters shone in a favorable light generally hold to. I’d have guessed more Catholic than Protestant, but there are plenty of negative on both sides. Parenthetically, I will say, I hardly ever see my belief tenets represented — not Catholic, not charismatic, not reformed.

But back to Enger. His depiction of miracle-working faith didn’t demand anything of the reader. There was no sense of “go and do thou likewise.” It is that point, I think, that makes non-Christian readers uncomfortable when they read a book that indicates there is a way that brings light, as Jill’s book did.

Becky

Becky,

I’m o.k. with sacrificing beauty for truth, because I don’t really think absolute standards of beauty exist, except (perhaps) in the mind of God. And while there are some things that would probably be pretty obviously not beautiful to God – snuff films, for instance – most other artistic objects exist in a grey area. We can’t logically prove why they are or are not beautiful. What I mean by Christian fiction having a different aesthetic, is that what may appear beautiful to Christian fans, may not be to secular fans, and vice versa. Christian fiction, at least CBA-produced fiction, operates by totally different rules than non-Christian fiction. Because of the influence of CBA-induced standards, Christian fiction is practically its own sub-genre of art . . . I’m not saying that’s bad, I’m just saying that many secular people, and many Christians who do not appreciate CBA’s valuation of truth over aesthetics, will have little appreciation for CBA-derived standards.

As for not appreciating the didactic nature of Christian fiction, I don’t think that’s really a judgment so much on Christianity (though that plays its part), as on all didactic fiction. People seldom read socialist realism today for the same reason. Socialist realists were so concerned with spreading the joys of Communism that they neglected aesthetic beauty entirely. Not saying that’s wrong, just that you need to be in the right frame of mind to appreciate it. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle has fallen out of favor for a similar reason . . . its great for three hundred pages, and then spends 70 pages on one long sermon about Christian socialism

(Points upward.)

Perhaps?

And this God is self-revealing. Ultimate, fully-known beauty is a mystery known only to Himself, for only He could know Himself, and only He is beauty. Yet He has shared some of that with us, in the commands and example of His Word.

The Tabernacle was beautiful (Exodus). The Psalms are beautiful.

Start there.

I believe I can. 1) This does not contradict the Word’s commands. 2) This makes me think of our wondrous, infinite God. 3) This view of God is as close to His revelation of Himself as I know how to make it, empowered by and trusting His Spirit. 4) I’m enjoying it as an act of faith, and so fulfill Romans 14:29. Optional: 5) This helps me anticipate future paradise, in the New Heavens and New Earth.

True, partly because either “set” may have very low standards in varying ways.

The way to prove “logically” whether Christian fiction’s aesthetic or rules is not to appeal to baseless “beauty,” but to Scripture’s standards and examples. Some of Christian fiction, and plenty of secular fiction, fails even rudimentary tests not because they fail to meet people’s approval, but because they contradict the Word — and the Word has plenty to say about true beauty, based in the Gospel.

However, truth/logic and beauty/emotion are not so separate as often believed. There is a beauty to logic, and logic cannot exist without satisfaction. (Thus the constant and entertaining tensions of Mr. Spock’s personality on Star Trek.)

… An oxymoron, by the way, in the view of this humble correspondent. If the New Earth will have private property ownership (Isaiah 65: 21-22), it’s plainly silly to aim for a more-“spiritual” or “just” culture than that, in a fallen world.

But specifically about Sinclair, I couldn’t agree more. It’s more propagandistic than any Christian novel I’ve read. For a class years ago, I was required to read at least an excerpt, and found it as dull and tasteless as the ingredients that American meat manufacturers were purportedly adding to their products; I may have even made this comparison in the essay I wrote about the thing. In that essay, I also did not see how anything in the work would have argued for Socialism, over and above better meat-manufacturing standards (optimally at the state level). But that, of course, crossed from literary standards to politics. A dangerous intersection, that. Littered with the wreckage of many a vehicle.

Dear Steve,

As regards to Christian socialism, I wouldn’t agree with your interpretation of those verses, even if taken literally. Indeed, it seems like a fairly perverse (not in the moral, but in the literary sense) reading of those verses. Isaiah, talking in an age where Israel has been progressively threatened by imperialist conquest from other nations (Egypt, Assyria, later Babylon and Persia) is pointing out that those (for their time) rich nations will no longer be able to profit off Israel. If anything, that passage is pro-Socialist; you’d also have to explain elements of the NT, such as Acts, which seem to support a limited form of socialism. I’m not saying the Bible is pro-socialist or anti-socialist. I’m just saying its pretty suspect to argue that we can gather what its economic philosophy is, since the context of the time period was so different. I don’t think anyone could reasonably argue, for instance, that Jesus was a supporter of capitalism – and the prohibitions on usury and the pre-Reformation suspicion of that practice shows that the early church was also suspicious of such profitmaking, albeit not always for the most noble of reasons.

As for beauty, what I mean to say is that I think God is suspicious of beauty, even though he certainly employs it in nature. Make no graven images and all that. I think Christians, particularly Christian artists, should be a lot more suspicious of the concept of beauty and eternal artistic values than they are. Those values of beauty don’t come from the Bible, but Plato.

Interesting theories about God and beauty. But how do they stand when confronted with the Biblical evidence cited above? There are a lot of “I thinks” and not so much “here’s what God’s Word says.” Then there’s a statement about how beauty concepts aren’t coming from the Bible — but unsupported, and without interaction with the above material.

I’ll intentionally dodge further extended socialism/capitalism discussion for now, because it’s not the main topic of the column! (Admittedly, I pursued that one.) Suffice it to say, Isaiah 65 is most certainly about the future, not-yet-arrived New Heavens and New Earth (verse 17). And not everything in Acts that is described is prescribed — e.g., the early Church’s “honeymoon” period which did not last.

I just read Morgan Busse’s Daughter of Light (loved it) and found it was overtly Christian, too.

I think, though, that there is a difference between people who are not Christians and people who are opposed to Christianity and offended by it.

It does seem that fifty years ago, people who weren’t Christians were at least familiar with the Bible and were not offended by Christianity as they are now. As sin has become more and more socially acceptable, the Bible has become less and less so.

Still, I hate to think that we can’t write Christian characters for nonChristian readers. I wonder, though, if we need to do it those who have been promoting the homosexual agenda have done it. They started out writing books with nice homosexual side-kick characters. After several years, they got to the point where they could write homosexual main characters. This was no secret agenda. They made it clear they were doing it. They discussed it. They set about making homosexuality acceptable to people and they did it in twenty years.

I’m struggling with this right now, because I want to write a book in which the main character is a Christian. But if he struggles with faith issues and comes to Biblical understandings, he’s going to seem preachy. If he struggles with faith issues and comes to the conclusion that there is no hell and God is in favor of extramarital sex as long as it takes place between consenting adults, he’ll be hailed as a loving hero. But if he sticks to the Bible he’ll be a bigot, I’m afraid.

Of course, I don’t plan to have him examine homosexuality or abortion. So…maybe.

But, no.

If he discovers that God is sovereign and is to be obeyed and worshiped by men who are created beings, he will probably seen as a hater. The world seems to view men as big these days and God as a sort of small Santa Clause figure who is keeping a list and finding out that everyone is nice and no one is naughty…except, perhaps the Christian haters.

OK…I think has officially turned into a rant!

Sally, you make a good observation that people’s lack of familiarity with the Bible might make Christian things less palatable. On the other hand, it also might make those things less noticeable. I remember reading an editorial after the first Narnia movie came out and the person said they’d read the book as a child and had no idea it had any religious implications.

I suspect there is a growing group of people who would see God in your story, depicted as sovereign and to be obeyed, as a tyrant, not a loving, good God.

I think it’s a real dilemma. Do Christians stop writing about our faith struggles? Aren’t those valid sources of conflict? Are we supposed to pretend that only Christians think about life after death and where we came from and what our purpose in life is, where we look for security and love? Are we supposed to pretend that God doesn’t speak to those big issues of life?

And if we pick up our beliefs and pitch the tent of our ideas in the safe haven of others who believe as we do, aren’t we agreeing with those who say we have no business speaking to society at large?

The more I think about this, the more I think we novelists have to find a way to speak to the culture at large.

Becky

I think outside the Christian market, any book that portrays Christians acting like Christians is going to be met with mixed acceptance. As someone mentioned, even the smell of Christianity turns some people off. Even having a character that believes in God makes them feel like someone is trying to “shove” religion down their throat.

I’ve already experienced that with one Canadian review of my first book in the Reality Chronicles. He returned it in an envelop (I was surprised he returned the book) saying he didn’t review “Christian propaganda.” This a book Muslims had read and been okay with.

To the non-Christian, it doesn’t seem “real” to them that people go around doing that, because they know so few people that do. And those they do, they look at more like Ned Flanders than a real person. So those types of people are only going to seem real to Christians who know people like that.

It reminded me when I was having one of my novels critted in a group, that someone asked me since my protag was Christian, wouldn’t he do X and Y at that point? Sort of the reverse expectation.

Interesting point, Rick. The expectations on Christian characters could easily come from both sides.

I actually am writing using typology, so this isn’t a personal issue in which I think there has to be one right answer, but the idea that Christians might either withdraw from or be shut out of the marketplace of ideas does not sit well with me.

I’d like to see us publishing in the general market. I’d like to see our stories with overt Christianity be published there. I think there are some stories, about Christians with problems only Christians face, that should appropriately be marketed to Christians. But a story about a character who chooses Christianity … why should that be a uniquely Christian story? I mean, I’ve read stories about people who own and love and race horses, but I’ve never owned one myself. I didn’t feel that those books were written only for horse owners.

I personally think we need to shake out of this mindset that Christian speculative fiction is really only for Christians.

Becky

Whatever we write, we must do it with — if I can be forgiven a marketing term — a target market in mind. And how often have we all heard agents and editors say “Don’t tell me your target market is ‘everyone.'”?

This goes back to that question of whether Christian fiction is written by Christians for “everybody” or by Christians for Christians.

Personally, I find it easier to think of my target market as Christians, and write accordingly. If I get negative feedback from non-Christian readers, I suppose I can live with that. Because, hey, at least they’re reading.

Very glad to see this topic being re-examined from various angles. Many of you already know I have plenty of strong thoughts on the subject. Perhaps here, the best way to summarize them is to offer quick-quotes views, or follow questions, in response to Becky‘s questions.

First I’d ask: what do we mean by Christianity? as in “this novel contains Christianity”?

I think when people say “Christianity” in this way, they really mean number 1, when number 2 would do just as well, and will likely lead to a more-powerful story.

Thus, instead of thinking a “Christian novel” requires a clear Gospel presentation, or works all things to that end (regardless of clarity), one could say that a “Christian novel” requires a fleshing-out or “simulation” of Gospel, i.e. Biblical, assumptions.

Like Scripture itself, this could involve clear, start-to-finish, tract-style Gospel content. Or it might not. More likely, the story will “clearly assume” the Gospel at its core.

Lewis, of course, kick-started this trend with his overt references to God, Maleldil, in his “real world” space-opera Ransom (or Cosmic) Trilogy; and of course the rulership of the land of Narnia by Aslan, the supposal-Christ of that alternate world.

I used to think it was because the fiction was poorly written. But that isn’t always true.

I recall a piece by Randall Ingermanson on this very topic. It pleasantly surprised me. He was the first to advocate, strenuously, that it is absolutely absurd to suggest that such activities don’t belong in a good, “crossover” Christian novel — because this is exactly the types of things Christians do. Why should our stories be different? If we want to have “realistic” fiction, why make claims about Christians’ lives that aren’t true — perpetuating lies by omission? (This also applies to fantasy-world “Christians.”)

Some should. Some shouldn’t. But those who should write and market to Christians should be truly writing for Christians. Saying “this is a Christian novel,” and then having a plot only about a nonbeliever coming to Christ, seems like a bait-and-switch. It also fails to challenge believers to see the Gospel “simulated” from this side of the Cross.

I suggest authors are spiritually free (limited by editors, publishers, and readers).

If atheists, Jews, Muslims, New-Age activists, and plain ol’ dull Meists get to be free about their themes and beliefs in fiction, why not Christians?

I’ve read From Darkness Won, but not Peace Like a River. Because you’ve read them both, Becky, I’m curious as to whether the latter novel explores Biblical faith from the view of someone who has long since accepted it and is seeing it fleshed out in the midst of the novel’s plot, or from the view of an outsider who has either just accepted it or is slowing growing into its basics (such as in From Darkness Won).

To be honest, such a story needs to have a sufficiently “vague” worldview.

I wouldn’t intentionally pick up a novel that has blatant, or latent, Muslim themes. This isn’t simply based on faith reasons. What hath these to do with my own life, after all? I wouldn’t be able to read such a story and see much connection to my own enjoyments.

Just recently I was thinking about this, thanks to the forthcoming The Avengers superhero film’s trailer. Some fans have mildly criticized Tony Stark referring to Thor as “a demigod” in the trailer (and presumably also in the film). I think the reason is easy. You just can’t call a character a “god” in a mainstream action film. Believe it or not, America is still too Christian-esque. So instead they say Thor is a “demigod,” or else emphasize that people on Earth only thought Thor, Odin, and others were gods.

So some novelists, and movie-makers, try to keep the films simply religion- “neutral.” Is this right or possible? Eh, not really, but it’s better than the alternative. Even “believe in yourself and follow your dream” humanism has some truth to it, barely.

Ultimately, good Christian fiction, for any audience, should relate to readers. For Christians, we share a common faith in God. But for non-Christians, we share something else — a common world, and many beliefs and philosophical assumptions, that honor God even implicitly.

Christian preaching must show the contrasts between man’s sin and God’s nature.

Stories must show similarities between the character’s world and the reader’s world — just as they show the similarities between Christians’ and non-Christians’ worlds.

This article is fascinating to me. I’m one of the most critical of reviewers of Christian fiction. The reason is that I desire to read books with a purpose, books that communicate the truths of Scripture. If the books are for Christians then they should encourage Christians to grow spiritually. If they are for non-Christians they should communicate the Gospel message and encourage non-Christians to become saved. What’s the point otherwise? Why even call your book “Christian” if it’s only morally good but doesn’t communicate why good morals matter? I write reviews of Christian Teen Fiction. I think the ones you mentioned are interesting. These are all books that have gotten extremely high reviews from me. These are the books I recommend to others. These are the books I proudly display on my bookshelf. I don’t care if the book is fantasy, realistic, adventure, sci-fi, sports, etc. If it’s going to be called Christian it must communicate the truth of Scripture. If someone thinks it’s too “preachy” then go read secular books. Christian books should communicate the truth of Scripture. The Bible never said to be ashamed of our faith or to hide it or deny it. In fact it says to stay away from meaningless talk. Ephesians 4:29 says to speak only that which will build people up according to their needs and benefit those who listen. 2 Timothy 4:2 outright says to preach the Word. So if you want to call yourself a Christian author, you’d better be preaching!

~ CTF Devourer

Devourer, I think I agree and disagree, so I’m asking for more of what you mean.

If the answer to both is “no,” then why hold Christian fiction to a higher standard?

I’d love to see some of your reviews. From what you wrote, though, it sounds like you mainly review based on truth content. While I don’t wish to downplay the importance of that, and also recognize that “beauty” is fleeting without truth, one must also review a work based on how it communicates truth — that is, beauty.

Going further back, as Kaci reminded us in a comment to this column, God in Exodus commanded the Israelites to make not replicas of the Ten Commandments or Law — which were specifically revealed, propositional truth — but items in the Tabernacle, such as garments “for glory and for beauty” (Exodus 28:2). The clear truth here: God is honored and exalted not only by truth repetitions, but beauty.

E. Stephen,

That is an argument my husband has challenged me on before too. Art for art’s sake. If God gave the talent, isn’t He glorified when it is used? Perhaps. Likely. But I don’t see a command in Scripture to make high quality works of art. I do see commands to preach the Gospel, to let your light shine before all men, to be ready to give an answer, to be His witnesses all over, go into all the world and preach the Gospel to every nation, etc.

You make a good argument using parables. And overall that is one of the strongest arguments for using stories to communicate truth – if Jesus did then it must be a good method.

But I still don’t think literature that hides the truth is as useful as literature that clearly communicates the truth. I just see it as a missed opportunity. If you have a chance to communicate the truth of Scripture to someone and don’t take it, then you missed an opportunity.

That’s my view anyway.

~ CTF Devourer

http://www.ctfdevourer.com

Hello again, Devourer (or perhaps I should call you something like “Shelly,” just as a stand-in that doesn’t sound so carnivorous? 😉 ).

Very glad to keep up with this discussion. It’s a perennial topic at Speculative Faith, and one that we keep exploring, we hope for God’s glory and others’ good. As you may note, the beauty-and-truth discussion also inspired today’s column!

Hmm, but I strongly disagree with that slogan. “Art for art’s sake” is impossible. “Whatever does not proceed from faith is sin” (Rom. 14:29). So art can be a sin! Moreover, art, if done for “its own sake,” is absurd, for “art” is not a person and cannot be glorified (the reification fallacy, i.e., personalizing the impersonal).

Art for God’s sake, though — that is very possible. We are (sub)creators, creating good things to honor the Creator, in whose image we are ourselves created.

Art for God’s Sake is also the title of a very good little book by Philip Graham Ryken. It’s very heavy on The Arts, though. Most Christians need a good, written, and Biblically based exploration of how Scripture influences all creativity.

Another excellent resource is The Christian Imagination, a collection of essays (though again more “literature”-heavy) edited by another Ryken, Leland Ryken.

Or: Definitely. The gifts of the Spirit aren’t limited to the epistles’ lists. Those are examples and not comprehensive! But even the gifts listed require creativity. Sermon preparation is an art. Paul’s rejoicing in God’s wisdom is an art.

And yet all of those are not the sum-total of the Gospel’s effects, are they? The Gospel definitely has something to say about salvation from sin, for God’s glory. Yet what comes next? The new convert only goes about trying to recruit others, so they in turn can recruit others? (Sounds like a pyramid scheme! 😉 ) Rather, we do do this, but it’s not our only goal. We’re saved to honor God in all we do. That includes how and why we enjoy stories, with their beauties and truths.

Moreover, souls are not all that’s being redeemed; human culture itself will be redeemed on the physical New Heavens and New Earth (Isaiah 65, Rev. 21). Sadly, humans who die in their sins will only know God’s wrath and justice forever. Culture, though, doesn’t come from sin, but was intended all along.

I like to say this, too: Some say stories don’t make sense in “the real world.” But in “the real world,” people enjoy stories. That’s what we’re up against.

Finally, if the Gospel only has something to say about sin, redemption, and evangelism, and doesn’t have much to say beyond those effects of God’s announced true Story, we need to skip the fiction entirely. Let us instead find the most efficient way of presenting the Gospel, straight-up, no-frills. That would lead only to nonfiction preaching and teaching, though — and not very good nonfiction preaching and teaching, when separated from means of reflecting on God’s nature. He is the Source of truth and of beauty. We need to see that, to bask in His attributes, and have both empower our evangelism and teaching.

Note that He varied His approach. Some parables were clear to non-believing others (such as the Pharisees who knew exactly who the murderous vineyard tenants were). Others were intentionally obscure. There’s room for both.

There’s a word I should have mentioned earlier: “useful.” I think we need to define this! You see, I’m a pragmatist. Whatever works is my slogan — yet what is the goal? To get people saved? That’s a good goal, but it’s unnecessarily limiting. To glorify God as He has revealed Himself? Now, that’s much broader, and is the ultimate end to which God does anything — including saving people, sending out missionaries, and gives people talents. (Cf. the Westminster Confession of Faith.)

God gave us literature that directly communicates truth (His Word). Yet, toward that end, we have examples both in early-Church history (like Paul on Mars Hill, co-opting a pagan poem in Acts 17), and in recent history (like C.S. Lewis and his “redeeming myths” in service of the “True Myth” of Scripture) to draw upon.

Perhaps. And yet oftentimes even overt evangelism takes years of planting and watering. Only the Holy Spirit can bring changed hearts through the miracle of regeneration — storming in, unpredictable and blowing (John 3) after years of conditioning on the “human” level through beauties, stories, witnessings, and bits of truth that float in the world amidst lies (thanks to God’s common grace).

As with the Bible itself and its “sub-stories” on the way to the greater Story, a Christian’s story can either present a fruit or portion of the Gospel, fleshed-out and “simulated” (this is what the Christian life is like, on the other side), or else repeat the whole Gospel account, so as to try to prevent all misunderstandings.

I believe Scripture gives us the freedom in Christ to do this in storytelling and story-enjoyment. That’s a Christian’s ministry as an individual. Yet as a member of Christ’s Bride (with his Church “hat” on), he must teach and witness clearly.

Meanwhile, as this topic of beauty and truth kept recurring here and elsewhere, I have begun a new blog series. Today: Beauty and Truth 1: Four Sorts of Stories.

Of all my general market novels so far, I’ve definitely had the most pushback on WAYFARER, the novel where I dealt with Christianity most explicitly. But that wouldn’t keep me from writing another book with an overtly Christian character, and/or that dealt with matters of faith and religious conviction, if I got a good idea for one.

I’ve actually been pleasantly surprised by how many general market editors I’ve heard saying they’d like to see more stories about teenagers dealing with faith issues, and not just in the stereotypical “kid from oppressive religious background finds freedom in agnosticism / atheism” either. I think there’s definitely hope, but the important thing is to be real and truthful about human beings in our storytelling, rather than creating cardboard “role model” Christians as the heroes and making equally two-dimensional villains out of those ignorant of or opposed to Christian faith. (Or vice versa, as some atheist authors have done.)

Rebecca, I wondered what kind of response you got about Wayfarer. That was a good example of a Christian kid having the kinds of questions that are natural in his circumstances. And that’s the kind of story I hope Christians continue to tell, not to one another exclusively, but out there in the marketplace with everyone listening.

And yes, there still is the issue of craft. If our characters are realistic and believable and three dimensional, and the plot is not predictable and lacking in tension, then perhaps we can tell our stories about Christians for the culture at large.

It’s great to hear that there are general market editors who are interested in stories dealing with faith issues. I can’t help but wonder, as I said to Kerry, whether that means faith with claims of exclusivity. I think the problem many have with Christianity is the idea that Christ is the one and only way to God. That seems to be a sticking point, even for some professing Christians. I wonder if a book about a Christian being shunned or isolated or bullied because of that claim would have a chance in the general market. 😕

Becky

Thanks Sally 🙂 It’s interesting you should say my book is overtly Christian. I actually had one of my critiquers say she wasn’t sure if it was Christian and was actually given low marks for the spiritual content of my book in contests :p

I agree with you, I think my book definitely has strong Christian themes. Two years ago I debated going mainstream, but realized that, if asked, I did not want to change the spiritual part of my book.

I wrote the story of my heart. And now I leave the audience to God.

From Becky:

I don’t think the problem is so much sacrificing beauty for truth as sacrificing beauty and truth. When stories settle for a caricature of Christianity, they don’t communicate, resonate, or convince. They echo all the repellent stereotypes that have dogged Christians for centuries and we’ve done little to dispel.

I think many Christians feel beset by the culture that surrounds them, and that feeling filters into our writing. We strike back by portraying intrepid Christians fighting against the overwhelming hordes of evil, or withdraw into a friendlier historical or fantasy setting, or project ourselves forward into an apocalyptic future where only Christians survive. The implications aren’t lost on the non-Christian audience…it’s us against them.

I don’t think most readers of any stripe have a problem with characters being Christians, and would respond positively to characters displaying Christian virtues organic to their lives. I think they’d respond even better to unpolished Christians wrestling with the problems inherent in connecting their faith with the challenges of life. The simple truth that’s often denied or ignored in Christian fiction is that when a person becomes a Christian, their problems don’t vanish. In some ways, they’ve only begun.

When characters start “acting like Christians,” and by that I mean it feels like they’re literally acting out a role, readers, Christian and non-Christian, sense fraud. Likewise, if the depiction of a character’s conversion has all the characteristics of a sales pitch, an audience bombarded with marketing every day of their lives will pick up on that.

With regard to reviews, I think the Amazon star system does an immense disservice to the integrity of both writers and reviewers. Positive reviews become meaningless, negative reviews get disproportionate weight and attention, and fine shadings of critical feedback, positive or negative, are lost in the noise. Social cliques can spam reviews and skew the numbers. It means nothing. What does make a difference to me is feedback, good or bad, from someone who felt it was important enough to send it to me directly or tell me face-to-face.

Wow!

I am new to writing and new to answering blogs, not sure if this will go through. BUT I had to make a comment. Good question! Excellent dialogue! My two cents: We CAN’T compromise our stories! We are writing for God’s glory, for His Truth, if we do anything less, then we are at fault. Let the non Christians complain (that just tells me that your/my story was used by God to touch the complainer). May it always be so. I pray the day will never come when we will be forced to be less overt. I may be idealistic as I am not published yet, but I do want to be an instrument for His use. Just my two cents….

LA