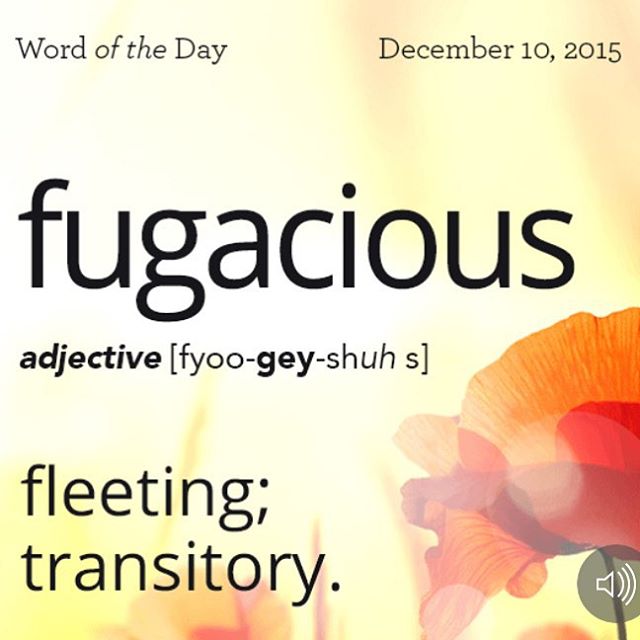

Fame Is Fugacious

Not long ago, I took a vocabulary quiz. In the process of it, I learned two new words, avulse and fugacious. It struck me as unfortunate that I would have to look long and hard for an opportunity to use avulse, and I would probably never get a chance to use fugacious at all. They’re just too obscure.

Not long ago, I took a vocabulary quiz. In the process of it, I learned two new words, avulse and fugacious. It struck me as unfortunate that I would have to look long and hard for an opportunity to use avulse, and I would probably never get a chance to use fugacious at all. They’re just too obscure.

We stand heir to a vast accumulated vocabulary, with words that range from everyday to rarefied to absolutely arcane. This has spawned one of those perpetual debates among writers and editors and agents, and in which readers have their own well-deserved opinions. The never-resolved question is: What words should writers use? What words are too old, too different, too long?

At the heart of the debate is a tension between two competing, legitimate principles. The first principle is that the ultimate aim of writing is to be understood. Far more than self-expression (because then why not just keep it to yourself?), writing is communication. You are not communicating if people cannot understand you.

The second principle is that writing cannot be reduced to the lowest common denominator. Some words are more apt than others, and sometimes the long word or the old word is the one that sings. Although writers should not, on the risk of being obnoxious, consider it their duty to expand their readers’ vocabularies, neither have they failed if they send their readers to the Dictionary.

The tension between these two principles is worked out book by book, sentence by sentence, word by word. There is no universal rule to lay down. I think it worth stating, however, that the thing really to be avoided is not the unknown word but the odd-duck word. These are the words that sound awkward or weird or (perhaps worst of all) funny. These are the words that jolt readers out of a text, and that is something all writers strive devoutly never to do.

Words often dro p out of use because language evolves and culture changes, and they don’t fit anymore. Consider the word “oxblood,” a shade of red that is not actually what you would imagine ox blood to be. Ox blood was once used as a pigment in creating dyes and paints. This would explain why oxblood is a dark color, and not the bright red we normally associate with blood: It was originally associated with ox blood that had dried or been mixed with other ingredients or soaked into materials such as wood or leather.

p out of use because language evolves and culture changes, and they don’t fit anymore. Consider the word “oxblood,” a shade of red that is not actually what you would imagine ox blood to be. Ox blood was once used as a pigment in creating dyes and paints. This would explain why oxblood is a dark color, and not the bright red we normally associate with blood: It was originally associated with ox blood that had dried or been mixed with other ingredients or soaked into materials such as wood or leather.

In our own day, when these associations have been lost, oxblood has lost much of its power. Even people who can define the word do not possess the images that first inspired it. Writers develop literary crushes on words, but it is good to consider whether those words, transplanted from the soil where they first grew, will truly thrive.

With most obscure words, the trouble is not dead cultural associations but simply the sound. Some are so unusual, so odd, that your eyes trip over the syllables. Others don’t sound like what they mean. This is the trouble with fugacious. It means fleeting, but to modern ears it only sounds silly, and I would sound silly, too, if I tried to used it (“Fame is fugacious”). Possibly, though, I could play it for humor: “My lunch hour was fugacious.”

By contrast, I have more hope for avulse (“to pull off or tear away forcibly“) because similar, well-known words like repulse and convulse also have vaguely violent meanings. Encountering an unknown word does not, in itself, jar readers out of a book. But the unknown word must flow, must give an impression in tune with its actual meaning. This is why you will not go wrong with words like invidious and deleterious: They sound as bad as they are.

There is a time, Solomon wrote, for everything, and probably for every word. No word should be summarily rejected, or uncritically accepted. In a living language, words fade away and sometimes ought to, but it takes a long time for a word to fade beyond all use.

Most of the machinery of modern language is labour-saving machinery; and it saves mental labour very much more than it ought. Scientific phrases are used like scientific wheels and piston-rods to make swifter and smoother yet the path of the comfortable. Long words go rattling by us like long railway trains. We know they are carrying thousands who are too tired or too indolent to walk and think for themselves. It is a good exercise to try for once in a way to express any opinion one holds in words of one syllable. If you say “The social utility of the indeterminate sentence is recognized by all criminologists as a part of our sociological evolution towards a more humane and scientific view of punishment,” you can go on talking like that for hours with hardly a movement of the gray matter inside your skull. But if you begin “I wish Jones to go to gaol and Brown to say when Jones shall come out,” you will discover, with a thrill of horror, that you are obliged to think. The long words are not the hard words, it is the short words that are hard. There is much more metaphysical subtlety in the word “damn” than in the word “degeneration.”

Chesterton, G. K. (Gilbert Keith). Orthodoxy (p. 117).

What a delicious GKC quote, Audie. Thanks so much for sharing it!

*makes mental note to read all his books again*

I’ve seen a form of “avulse” in medical terminology: “avulsion” as in nail avulsion (mental screaming, because there were usually pictures) or even digit avulsion (slightly louder mental screaming).

The color swatch for “oxblood,” by seeming coincidence, looks almost identical to the redesigned SpecFaith navigation bar (as of this past summer).