C.S. Lewis Redeemed Myths, and So Should We

When C.S. Lewis wrote The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, he included a most surprising figure. No, I don’t mean Father Christmas (the merits of whose inclusion are a discussion for another time). I refer to Mr. Tumnus.

The nicest faun Lucy Pevensie ever met.

As E. Stephen Burnett has pointed out before 1, fauns in classical mythology were often far nastier than Lewis’ depiction. Considering his literary predecessors (and even some of his descendants, such as the Faun in Pan’s Labyrinth), Tumnus’ appearance in a children’s book might seem an odd choice. Even if Tumnus isn’t like those other fauns we’ve heard of (they’ll say anything, you know), there’s still a connection.

Some might say that Lewis’ portrayal of Tumnus (his narratively brief service to the White Witch notwithstanding) serves only to sweeten or sanitize the fauns of mythology. Perhaps that is one consequence of Tumnus. But I think what Lewis accomplishes with Tumnus is something greater: the redemption of a myth. Lewis does this with mythical creatures and legendary figures throughout his writings, but especially in Narnia. Centaurs, fauns, Father Time, and even pagan deities like Bacchus and Silenus, Eros, Venus, and Mars—all of these find new life under Lewis’ pen

This is not the Tumnus you’re looking for.

This mythic redemption is a literary working out of Paul’s admonition in 2 Corinthians 10:5 to “take every thought captive to obey Christ.” Normally, this verse is (rightly) applied to self-control in one’s own thoughts and to discourse and debate in which wrong thinking must be corrected and made “captive” to Christ. But when it comes to fiction, it is possible for us to take a different tack on the subject, as Lewis does.

A fun romp through faerie not to be missed.

This redemption does not mean that every myth must be sterilized or made impotent. Indeed, removing the power of a myth would make it worse than worthless. And Lewis is far from the only author to take myths beyond their pagan roots and (rather than simply Christianizing them) give them new life under Christ. For instance, in her novel Paper Crowns, Mirriam Neal presents figures like the Morrigan and Cernunnos as powerful but subservient beings. 3 The horned god Cernunnos becomes a Treebeard-like guardian of the forest, fearful in his power but a servant of the Light nonetheless. The Morrigan, true to form, remains a slippery ally at best but still finds her place in the larger pattern of the world.

Other authors have set their hands to similar mythic redemptions. Arthurian figures such as Merlin and Arthur are among the most common to be given this treatment (such as in Bryan Davis’ Dragons in Our Midst series or Lewis’ That Hideous Strength), likely because there is already a tinge of Christianity in most people’s understanding of those legends. But this sort of redemption can reach far beyond the “easy” myths.

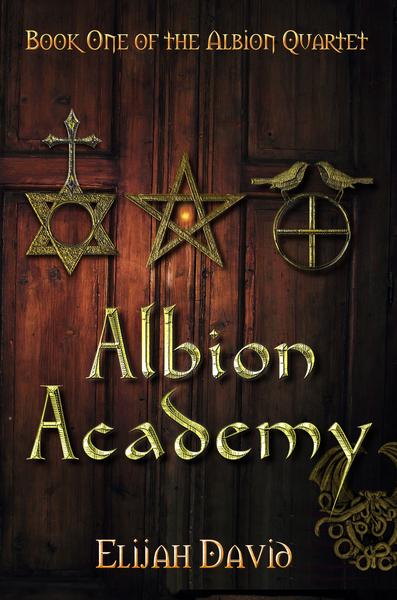

Albion Academy is due out later this month

In Albion Academy, my main characters are a Djinni, a Valkyrie, and a descendant of Merlin’s (yes, I have the “easy” myths in there, too). One of my hopes with this novel is to do what Lewis did: redeem these myths. So I have a Djinni whose faith drives his actions, a Valkyrie who questions her place in the universe as a reaper of the dead, and a wizard who craves something beyond his magic.

What other books have you seen where a myth is raised above its origins and given a Lewisian redemption? What books would have benefited from such a treatment?

- Speculative Faith Reading Group 2: Meeting Mr. Tumnus. ↩

- Susan and Lucy even say it is only Aslan’s presence which allows them to feel safe during the romp of the gods. ↩

- For my discussion with Mirriam on this topic, see Paper Crowns and Redeeming Myths. ↩

Amen, brother! About time somebody said it. I’ve been slightly afraid of including mythological characters in my stories (not THAT afraid, because if people have a problem, they’re going to have a problem.) for this reason, but these character archetypes I believe are around for a reason… for our enjoyment and enrichment. So I’ll have my centaurs, fauns, dryads and hamadryads and write them for the glory of God.

Precisely. Stories are one of God’s great gifts to us. We should make them (and in some cases, reclaim or redeem them) the best we can.

You make a great point! In my (as-yet unpublished) modern faerie stories, I try to highlight the fact that the Fae and all other supernatural beings are subject to God–not outside Him. If He is powerful enough to create humans, isn’t He powerful enough to create other sentient beings? This is my little way of reclaiming myths–or in my case, folktales. 🙂

That’s the view I take of it in Albion Academy as well. If these creatures and beings exist, they must exist in subjection to God (or rebellion, as the fallen angels, but even they are subject to God in the end).