Books Have Themes?

Fifteen years ago, one of the big knocks on Christian fiction was that the books were too preachy. This complaint seemed to reach writers who then proceeded to ditch any themes, at least ones purposefully crafted. After all, one sure way to not preach is to not say anything at all. In fact, stories should just entertain, never mind this moralizing, philosophizing, and sermonizing.

Fifteen years ago, one of the big knocks on Christian fiction was that the books were too preachy. This complaint seemed to reach writers who then proceeded to ditch any themes, at least ones purposefully crafted. After all, one sure way to not preach is to not say anything at all. In fact, stories should just entertain, never mind this moralizing, philosophizing, and sermonizing.

Themes began to disappear.

Until a number of writers noticed that general market books and movies and even TV shows had themes. Some of them even preached.

The truth is, using the vehicle of theme, writers say something. Whether that something is trivial and mundane or significant and profound depends on how unafraid they are. Yes, unafraid. Many writers are afraid they will limit the scope of their book if they place their story firmly in a particular economic or political or religious milieu. They’re afraid if they take sides in a controversial question, they’ll make enemies and lose readers. Some are afraid they will be labeled “preachy” if they include meaningful themes in their stories.

According to a number of writing instructors, novels that name specifics—details brings a place or a person alive, and that includes specific themes—engage readers in a way that generic stories don’t. Consequently, writers that steer away from presenting a particular view point, whether religious or political, are actually neutering their story. From agent and writing instructor Donald Maass:

What distinguishes our era? What are its look, buzzwords, issues, and conflicts? Fashion magazines, op-ed pages, sports reporting, rappers, corporate websites, and teen slang are all barometers of our times . . . I don’t mean to suggest dropping in brand names or news events. Those are shallow gimmicks. I do mean that an important component of any novel’s grip on readers’ imaginations is how that novel brings alive its times. (Writing 21st Century Fiction, p. 168—emphasis mine)

Certainly speculative novels should do both—bringing alive the times in which the story is set but also bringing alive the themes that will resonate with people living in the real world.

The fear of dating a novel scares off some authors from creating the kind of particular atmosphere that makes a story feel as if it’s anchored in reality. However, stories like The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck bring alive a time and culture through which the author can then say something important and universal, something that applies today as well as to the original audience.

Some writers also fear taking a stand on a controversial subject or saying something significant about an eternal question. And more so in these recent days since “author shaming” or bullying has become a thing on twitter (see L. Jagi Lamplighter’s recent article on this subject). Maass again:

The mysteries of existence are also often avoided in manuscripts. Do you believe in destiny? Do you believe in God? Are our lives random or do they have a purpose? Do you think about these things? Of course you do . . . What about your protagonist? What’s her take on the big questions? Is it pretentious to include them?

Ducking the big questions is easy. So is achieving low impact . . . Is there such a thing as justice when laws are made by fallible humans? Does do no harm have any meaning when medicine becomes guesswork? Is it worth building bridges when their ultimate collapse is guaranteed? Do we teach in schools “truths” that are untrue? Does the accumulation of capital do good or does it corrupt? What are the limits of friendship? Should loyalty last beyond the grave? We read fiction not just for entertainment but for answers to those questions. So answer them. (Writing 21st Century Fiction, p. 169-170— emphasis mine)

A good many writers are afraid of answering these kinds of questions, thinking that by doing so they’ll come across as preachy—that death knell to Christian fiction.

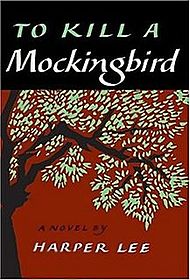

But having something to say does not equate with preachy writing. Harper Lee had some specific things to say about prejudice, but I’ve never heard anyone claim To Kill A Mockingbird was preachy. That’s because Ms. Lee didn’t explain what she had to say: she showed it through her characters.

But having something to say does not equate with preachy writing. Harper Lee had some specific things to say about prejudice, but I’ve never heard anyone claim To Kill A Mockingbird was preachy. That’s because Ms. Lee didn’t explain what she had to say: she showed it through her characters.

She didn’t have one of them sum up the meaning of all the events or spell out the ethical implications of why they did what they chose to do. Rather, she created believable people who lived in a specific time with a certain set of problems, and she showed one man and his daughter who lived in contradiction to the societal norm.

Clearly she tackled her subject unafraid, even in the racially charged era of the pre-Civil Rights movement, and the result was a classic story with timeless truths, still being read and studied fifty-plus years later.

Shouldn’t Christian authors be the most unafraid of all? Shouldn’t we be putting spiritual truth at the forefront of our themes? Shouldn’t we do so intentionally, taking care to craft our themes as carefully as we craft our characters?

After all, aren’t the best books the ones that make us think and ponder long after we’ve come to the end and returned the book to the shelf or to our Kindle collection? And shouldn’t Christians aim at writing the best books?

Not sure how everyone feels about this, but if the plot or story doesn’t feel like it’s going somewhere, or serving a purpose, it’s much harder for me to pay attention to it or find it meaningful. This means that without a theme or at least an attempt to communicate/illustrate something, the story is more likely to feel pointless. There may be times when a story can resonate even though the author wasn’t intending to communicate anything, but that was probably because regardless of the author’s intentions, meaning could still be gathered from the tale.

Of course this doesn’t mean stories should be preachy. It’s much harder to like preachy stories unless the author can make them entertaining enough for everyone to ignore the preachiness. But that doesn’t mean the stories shouldn’t have some sort of purpose.

Something I learned from plotting one of my future Naruto fanfics, though, is that the point of the story doesn’t need to be encapsulated in the ending. Maybe in that fanfic the ending helps drive the point home (the accidental isolation of the main chars ended up being dangerous for them). But the story is less about that, and more about how isolation and mistrust affects the two main chars as they grow up.

Athough the chars are good people, growing up under their particular circumstances changed a lot of how they interacted with others, where their priorities are, etc. The chars themselves aren’t even entirely aware of the story’s point, and the audience isn’t called to take a specific action. The story, instead, probably serves more as an opportunity to observe, understand, and empathize. And maybe doing so will give readers insight into human nature that will improve their lives in the future.

Maybe that approach (having the point subtly illustrated throughout the tale rather that having it culminate in an obvious way at the end) can be a good stylistic approach for those that want to say something without feeling preachy.

It’s completely about crafting theme well. With the exception of, perhaps, an allegory along the line of Pilgrim’s Progress, nothing should be “obvious,” if it comes at the end or the beginning. We have simply lost the understanding that theme≠preaching. We think, meaning will naturally seep from our worldview into the story because it’s part of us. But that doesn’t make sense. We are “characters” and we still work hard to craft our characters. We live in the world and we still work hard to construct our storyworld. It’s simply off to think that we can make our stories about nothing in particular and meaning will jump out anyway.

Becky