Advice From “The Story Of My Heart” Part I

Okay, so my last six articles have been about aliens. Maybe I should explain why a Lutheran pastor has little green men on the brain so badly. And in doing so, I’m hoping to pass along two bits of advice that I’ve either received or kind of figured out along the way.

Like I said a few articles ago, what got me on the whole “how do aliens fit into God’s plan of salvation” business was a class I took in the Seminary called “The Gospel and C. S. Lewis.” Long story short, one fall day I sat down and started piecing together an idea. I grabbed two of my friends and forced them to listen to me ramble for forty-five minutes, going over the plot ideas that had sprouted in an overly-fertile imagination. They suffered through it and, once I was done, told me to go for it. Write my heart out and get that story on paper. And thus began a long and winding journey, one that’s taken longer than a decade.

Only here’s the thing: my soon-to-be-published book, Failstate? Yeah, there isn’t a single alien in it. Well, that’s not entirely true. Not exactly. Never mind, that’s not important. Plus I don’t want to give away too many spoilers. The upshot is this: I was sure that that idea would one day be my debut into the world of Christian speculative fiction. Only now, when I’m on the cusp of my debut, I’ve done a 180 on the idea. It may never see the light of day.

Does that mean that I’ve stopped believing in it? Not at all. I love the characters I created for that story. I spent a lot of time crafting the world(s). There’s one alien species that I’m particularly proud of. And I stand behind the spiritual payload I wove into the story. And yet . . .

So let me spend some time telling you a story about a story, one I call The Leader’s Song.

After that forty-five minute recitation, I started working feverishly on creating this story. I wrote multi-paged outlines for the plot (yes, I’m a plot-firster and a outliner). Then I started work on what would turn out to be an epic science fiction tale, one that blended the best traditions of adventure, space opera, and Biblical historical fiction. Seriously. Stop laughing.

Here’s the problem I ran into, though: by the time I was done telling the tale, the entire thing had blossomed to the size of three books. I don’t remember the final wordcount, but it was somewhere hovering in the 300k word range.

No problem, I figured. I’d simply chop the behemoth into three individual parts. Instant trilogy! Who wouldn’t want to publish that?

But I’m getting ahead of myself here, just a little.

Shortly after finishing the manuscript, I joined American Christian Fiction Writers and attended my first conference in Dallas. Even though I had been told it wouldn’t happen, I figured that I had such a great idea, someone would certainly be interested in my story. I was sure that The Leader’s Song trilogy would be my way in.

Strange thing, though. No one was interested.

Well, that’s not entirely true. I kept getting mixed signals. Some people, when I told them about my book idea, absolutely loved it. Others, though, didn’t like it at all. I couldn’t quite figure it out.

It wasn’t until I got home and had some time to think about it that I realized what the difference was: whenever I told a writer, whether published or not, about my story idea, they all loved it. But when I told editor and agents about my story, they all said, “No.” It drove me up the wall. Why the difference? And who should I listen to?

In the end, I realized that the publishing professionals were right. They spotted a major structural problem with my trilogy, one that would easily sink it. I’m not saying that the other writers were blind to it. But at that conference, I realized that a writer has to be careful whose advice and criticism they give the most weight to.

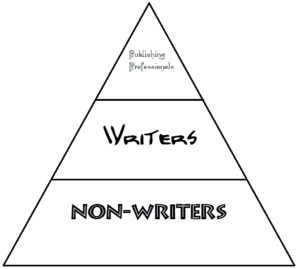

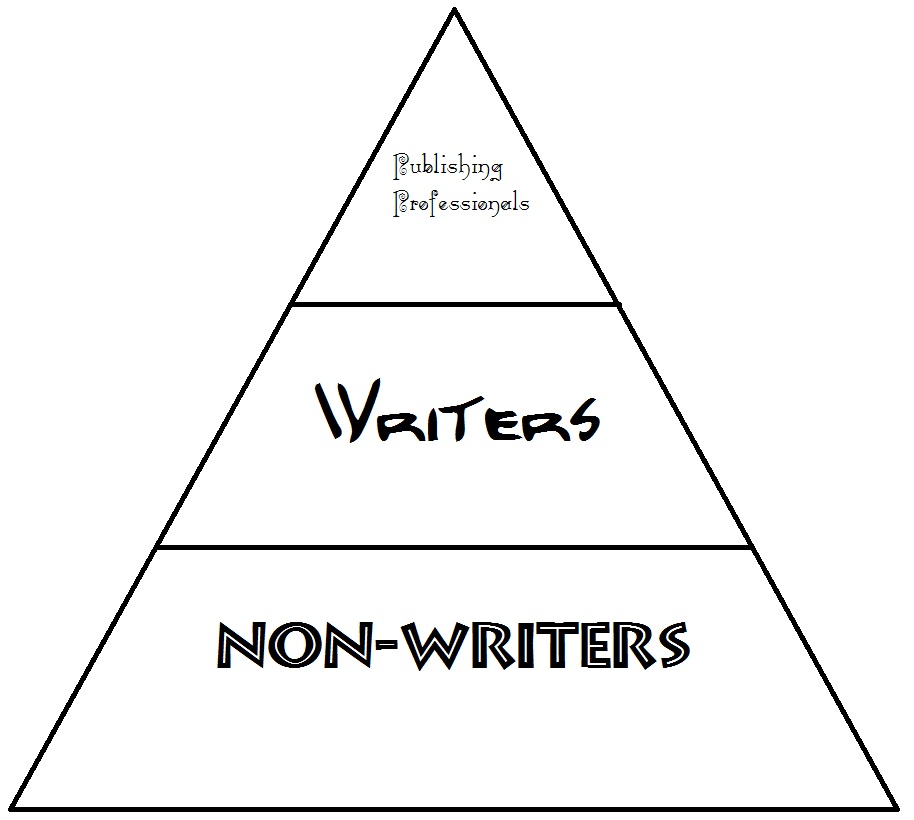

To put it another way, there’s a hierarchy of sorts when it comes to criticism about our stories. One could even chart it out on a handy-dandy pyramid. At the bottom are the non-writers, people who have never written a story or even part of one. Is it okay to show your work to these folks? Absolutely! But will they know their stuff when it comes to criticizing your work? Some will, some won’t. Some might not want to hurt your feelings and will thus hide the fact that they fell asleep half-way through the manuscript. The point is, while it’s easy to get a non-writer to read your writing, their criticism, while well-meaning, shouldn’t be given as much weight.

To put it another way, there’s a hierarchy of sorts when it comes to criticism about our stories. One could even chart it out on a handy-dandy pyramid. At the bottom are the non-writers, people who have never written a story or even part of one. Is it okay to show your work to these folks? Absolutely! But will they know their stuff when it comes to criticizing your work? Some will, some won’t. Some might not want to hurt your feelings and will thus hide the fact that they fell asleep half-way through the manuscript. The point is, while it’s easy to get a non-writer to read your writing, their criticism, while well-meaning, shouldn’t be given as much weight.

Further up the pyramid we have our fellow writers. Because they have walked this road before, their advice is more trust-worthy and valuable. They’ve likely encountered similar problems as you have and, as a result, will be able to help you through it. They’ll be able to help you evaluate ideas, ferret out problems in the text, and act as cheerleaders as you keep on keeping on. It’s great to have your fellow writers give you advice, encouragement, and criticism. But, as I found out, sometimes that criticism can fail you, especially if you’re seeking to be published.

The gold standard for criticism will always be (at least, in my grubby little opinion) the professionals of publishing, agents and editors. Part of the reason for that is obvious. They’re the gatekeepers, so to speak. They’re the ones you have to convince to take a chance on your writing (unless you self publish). But more than that: in the course of their work, they see more good and bad stories than we ever will (I think more of the latter than the former). Because of that, their advice should almost always be trusted, especially if they’re willing to give it.

Now I’m not saying that non-writers will always be wrong and publishing professionals will never make a mistake. But the lesson I learned from the “story of my heart” all those years ago is something that I’ve tried to pay attention to over the past several years and I think it’s served me well. It’s good to listen to advice about writing. But be sure that the source is trustworthy.

Next time, we’ll talk about one of the hardest lessons I’ve had to learn and the reason why “the story of my heart” will likely remain shelved for the foreseeable future. Until then.

Even if you’re not seeking critique, the same holds true. I know that if I want someone to read my stories, I’d be better off with an online friend who loves reading fantasy than my parents who rarely have time and , if they do, prefer modern realistic.

That’s very true. My father has yet to read anything that I’ve written. The same thing is true for my wife. They say they’ll read Failstate when it comes out. We’ll see. 🙂

Alas, that’s sad to hear. A writing curriculum I read in my youth once asked, “Ask yourself if these characters would bloom better in a different garden.”

You can still take your characters and ideas and just put them in a different story. A better story. I have a couple of characters who are great on their own, but I can’t come up with a story for them to save my life. I’ve tried various things, and I think I’m getting closer.

I also have an entire 60k story that I’m going to scrap entirely except for one subplot, because the subplot was better than the entire rest of the story. (And maybe the setting, because I liked the world.)

It’s just part of the growing process as a writer. I’m there with you, friend.

I’m getting a little ahead of myself here, but I haven’t completely given up on my story. Not just yet. I’ll explain more in two weeks, but your comments about taking the favorites and re-using them is a great point. Maybe I’ll speak a bit more on it next time.

John, I enjoyed this. You’ve done your work well in relating your experience, and in helping other writers.

I did get a bit of a sinking feeling toward the end, wondering how my work is seen. But that’s okay. I’ve experienced a lot of those, just not recently.

Thank you!

Maria

John,

There’s a shoe left to drop in your story, so I don’t want to disagree too strenuously at this point, but the hierarchy bothers me a bit. It reflects an assumption that feedback from the publishing community is inherently superior to that from writers, which in turn trumps feedback from the public at large. I think it’s not so much that one is better than the others, but rather that they’re different kinds of information, and as you noted, it’s important to carefully discern your feedback and decide how to use it.

Publishers can weigh-in on worksmanship, certainly, but their focus is marketability and risk management. This can become something like the “beer goggles” I talked about last week–they’re attracted to books that look like smash-hit novel X from last year. A mediocre story by a known author or celebrity with a guaranteed audience will receive a warmer reception than a masterpiece by an unknown. Many successful stories have been turned away by a long parade of publishers before they were found by one who recognized their potential and was willing to risk commitment.

Writers are a great source for technical critique and information about what has and hasn’t worked for them in the past when dealing with agents and publishers. Writers are also readers, though I find they tend to enjoy and appreciate different qualities in a story than non-writers. They’re a niche market all to themselves.

Publishers may be the gatekeepers (and self/indie publishing has undermined that role significantly), but non-writers are the ultimate audience, and the ones who will, in the end, decide whether or not your book will sell. If they love it, their support can overcome a publisher’s hesitancy toward an unknown writer. Of course, figuring out what they’ll like, before they know it, often seems like an obscure flavor of black magic.

And with all respect and affection to the ACFW, color me not surprised that publishers/agents at their convention weren’t interested in a science fiction story. They were the American Christian Romance Writers not so long ago, and that worldview is still dominant in the organization and among their fellow-travelers, I think.

I’d encourage you to not give up on that story, and when you think it’s ready, push off into the deep water, spread your net a little wider, and keep casting it out there until you catch something.

Fred, you’ve added substantially to this discussion. Very encouraging! Yes, in the end readers will decide, that is, if you get by, or slip past, the gatekeepers; that is, if the Lord says, yes, that He wants your work out there, he wants people to read it. And, yes, it is a sort of black magic, peering into the future, picking up vibes, about what will please readers and succeed.

Maria

I’d maybe go so far as to say “readers” need their own category outside “non-writers.” Someone who loves books, theatre, and film will – or even dance, music, and art – will appreciate the end game even if it’s not their medium. That’s a different place than someone completely removed from the storytelling world. Know?

This is a valid point also! Apparently I didn’t think through this post all that well. 🙁

Haha. I don’t know about that. My comment was purely from personal experience.

These are all great points, Fred, and I don’t disagree with you at all.

And I understand what you’re saying about ACFW and their rather . . . well, romantic focus. Would it help if I outed the industry insiders who critiqued my story? It was Jeff Gerke, Steve Laube, and Andy Meisenheimer, all three of whom are very sympathetic to the speculative fiction genre. Thing is, all three of them zeroed in on the exact same problem, something that the writers overlooked or said wouldn’t be that big of a deal.

Perhaps I’m extrapolating too much from my one experience, but I’ve often seen the exact opposite trend when it comes to criticism from industry professionals (i.e. “Well, what does s/he know, s/he’s just an editor.”). I suppose the difficult thing to do is find the right balance and know if the advice is good.

I can totally feel where you’re coming from, John. The original story & characters that spawned my world of Sauria will never see the light of day in it’s original format (weaponized pogo sticks & skateboards? really?)… Though perhaps one day I’ll get to tell that story revisioned within the world of Sauria as published. I hope your original story can see the light of day eventually too, even if it isn’t isntantly recognizable.

As far as guaging feedback, the number one trait that a person must have in order to give appropriate critique and advice is a strong understanding of your audience and your goals.

If you’re writing pulp sci-fi, and your goal is to write the best pulp sci-fi book you can, then you can listen to a literary writer or historical editor for some feedback, but will it carry as much weight as someone who is steeped in the field of pulp sci-fi, even if they are just a reader?

Of course if your writing is pulpy and you’re striving for literary, the pulp critiquer will be less helpful than someone of a literary bent.

Critiques and advice from almost anywhere can help us become better writer’s of course, but it must always be filtered based on if the source is helping you get toward your ultimate goal both artistically and practically.

I look forward to seeing where part 2 of this series goes.

That’s an excellent point as well, Stuart, that if the industry professional knows little about your genre, you’re better off ignoring them.

What Fred said! Seriously, I decided to comment because I wanted to sort of stand up for the views of non-writers. Fred said it all beautifully, but here are my additional pennies. Readers may not be able to explain what technical writerly thing made them not like a book, but they can sure say what they’ll enthusiastically recommend and what author they’ll never, never read again. In other words, their opinions are valuable, necessary, and should be helpful

In our little Openings feedback, the central question is, Would you want to read more of this one? It’s the same questions editors at a particular conference answered in one of their workshops. But readers can answer that one too. The difference will come in the “why or why not” part. Editors can tell you precisely what they’re looking for. Readers may or may not be able to nail it down.

What a writer needs to know, though, is how both those groups see his work. Editors need to be the first buyers, but readers hopefully are the greater audience. Consequently, I’m hoping we can invite a lot of readers over on Monday to give feedback to the randomly selected Openings. Editors and agents are welcome, too. And yes, other writers. We are on different places, and some will have more expertise to share than others.

I don’t think any feedback is wasted, but as Fred said, it’s important to know how to evaluate what we hear.

Becky

My goodness, it seems that I’ve stirred up a bit of controversy. 😉

You know, I agree with what you say here too! Perhaps I overstated my case a little. Sorry, folks! I’ll do better in the future.

Not controversy, John, discussion. You got us thinking, and that’s always a good thing! 😉

Becky

Hurray for controversy! And thanks for sharing this, John. It’s a topic well worth talking about.

Hmm…that may be, as we say here in the land of Oz, a horse of a different color. I’m curious to hear about the problem they found in your story, and why this persuaded you to set it aside.

I think it is important, if possible, to hire an editor who has been in the publishing business who can give you feedback on the project. It increases your chances of getting the project published by informing you of all the problems that you, and almost every other writer and some would-be editors, cannot see.

John, it’s not that you didn’t do well–not at all! It’s just that posts are the start of a discussion.

Steve Laube declined to represent me, but gave me good advice about the naming of my fantasy realm.

Maria

John, I thought it was a great post and brought up some good questions. Each group in your pyramid provides a specific type of critique:

Readers-are they interested in your story? Because if the story isn’t interesting, then who cares how well it’s written?

Fellow Writers-ideas on how to improve your story and encouragement.

Editors and Agents- generally they provide deeper insight and can help a writer take his/her work to the next level.