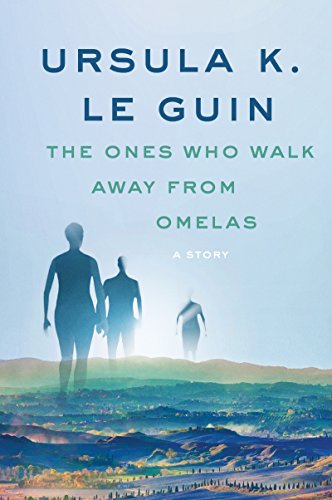

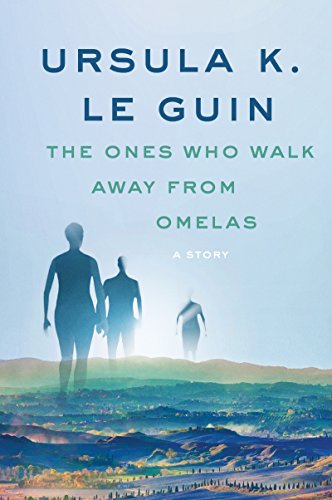

‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’: A City Without Guilt

I listened to a lecture series called How Great Science Fiction Works, from The Great Courses.

I was actually more of a sci-fi fan when I was a child. This was the time of the first Star Wars movies and the first Battlestar Galactica series. Often I would go to the library and find books about Tom Swift, and even older stories about Lucky Starr and Tom Corbett, Space Cadet. Even though I’m not very much into sci-fi now, I still found those lectures fascinating and informative.

One of the lectures focused on utopian and dystopian stories, and the lecturer, Gary K. Wolfe, begins and ends this lecture by referring to a particular story, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin.

This was enough to pique my interest in this story, and to read it for myself.

This was enough to pique my interest in this story, and to read it for myself.

“The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” is a very short story, though it may be called a story in only the loosest of senses. It is more a description of this city called Omelas on the day of its Festival of Summer, and what they people are like, what activities they will engage in on that day, and their overall happy and joyful state.

In fact, the author treats Omelas like a tabula rasa. It’s if she were creating the city as she wrote about it. She even invites the reader to assist in creating this paradise.

Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale, long ago and far away, once upon a time. Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids, assuming it will rise to the occasion, for certainly I cannot suit you all.1

There is, then, a fluidity to this fictional city, as Omelas becomes, not one person’s utopia, every one person’s utopia. And while I would guess the author would not agree with every element anyone else might put in or leave out, that is of secondary importance to the overall point.

For while Omelas is a paradise on earth, it is a paradise that comes with a price.

One person in the entire city is not happy. This single child (whose gender isn’t named) lives shut in a small room under one of the buildings. Its room offers no comforts, not even even a toilet where it can relieve itself. This child is alone and no one speaks to it. The only care it receives is that someone gives it a little food each day. The child is mentally deficient, so it doesn’t understand the reasons for this treatment. Yet, somehow, the happy state of all of the other people in Omelas depends upon this one child’s misery:

“They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas. Some of them have come to see it, others are content merely to know it is there. They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.”2

The conditions are firm: “The terms are strict and absolute; there may not even be a kind word spoken to the child.”3

But not all the people of Omelas can accept this arrangement. So this story essentially gives us two kinds of people. One group knows about the child and may pity it. They may even wish they could do something about its condition. But in the end they do nothing to help that child directly. The second group, for reasons left unstated, walks alone through the streets of Omelas. They pass through the beautiful gates, the farmland outside the city gates, and head toward the mountains, never to return.

Le Guin tells the story in such a way as to make the reader feel sympathy for the city’s people. They are not unfeeling, uncaring monsters who rejoice in this child’s sufferings. But the truth is still that they accept the terms of this mysterious agreement, they enjoy their good lives while accepting that they do so only because of the one being left alone to suffer in misery. And so it seems that it is those who walk away from Omelas who are the better, more noble people.

A few years ago, I did a small bit of research into North Korea. I read books and online materials about people who have escaped that place. They told stories of starvation and oppression, and the dangers they faced trying to find a better life in another place. It was very eye-opening. Though I had some small knowledge, mostly only that North Korea was a bad place, my research gave me a stronger idea of what those people suffered and what the people still there are suffering.

When it comes to a place like North Korea, I feel no need to blame someone for wanting to leave. This nation’s problems cannot be solved by one common person. I want to make that point, because when I look from that real-life place to the imagined utopia of Omelas, I find myself less sympathetic to those who walk away. That’s because they merely walk away. I think that way because of two reasons given in the story itself.

The first is simply that there are not just two kinds of people in Omelas. There is a third: the child itself.

Those who walk away from Omelas may consider themselves noble for leaving behind that place and setting off on their own, though they may not know where they are going. But the truth is, they are not really any better than those who stay. Those who stay in Omelas enjoy the good things of the city, and those who walk away decide they cannot enjoy them any more. The truth. however, is that nothing has really changed. Omelas is still Omelas. It’s still a corruption, still a lie, still a place based on lies.

This brings me to the second reason. The author reveals several important facts about this city. She describes the religious practices of the people of Omelas—practices that avoid graphic details but are clearly shown to be sensual and sexual. “One thing I know there is none of in Omelas is guilt.”4 Later, when telling us about why this one child is isolated and made to suffer and why no one can do anything about it, she adds:

“If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms. To exchange all the goodness and grace of every life in Omelas for that single, small improvement: to throw away the happiness of thousands for the chance of the happiness of one: that would be to let guilt within the walls indeed.”5

These are the lies: that there is no guilt in Omelas, and helping this child would let guilt into the city.

Because the truth is much the opposite. Even if one wants to disregard the obvious and gross immorality the author describes when talking about the religious practices of this city, the people of this city are still guilty of this one child’s wretched condition. They are guilty of being selfish and valuing their own pleasures over the good of this child. Instead of loving their neighbor, this child, they love themselves. They are guilty of blinding themselves to their own guilt, for while they may think themselves without guilt, they are simply believing a lie.

And those who walk away from Omelas have not escaped their own guilt, for while they may walk away from Omelas, they also walk away from the child, leaving it in the same miserable condition. Their leaving has no affect at all on that child, and would be cold comfort indeed if it could somehow know about their actions. Their cold nobility is as selfish as the others’ acceptance of the conditions.

Omelas isn’t a utopia. It is a place filled with guilt.

Where, then, is the fourth kind of person? Who will offer this child the forbidden kind word? And who will take that child from its filthy prison and take it to the sunlight? Will this hero clean and feed and comfort the victim while all the lies of Omelas burn down all around them?

Or, to ask the question another way, where is the true church of Christ doing what it should be doing, preaching the law to destroy our illusions of our own goodness, then preaching the gospel to show us where our sins may truly be washed away?

Good thoughts. As I read I got angrier and angrier at the people who left. “Why aren’t you helping this child! Go rescue him! Show people what they are doing to him!” The people of God should always be the fourth type.

Exactly my thoughts when I read it back in college. Safe to say, I didn’t want to read any more of Legs Guin if this was to be the only options for those people.

I wonder if Le Guin was trying to grapple with the idea of “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

In any case, I’m pretty sure she was aware of the change in thought around Omelas and agreed with it. I find her a particularly hoopy frood of an author because she was aware of the conversations around her work and never seemed to act as though they were a challenge to her authority as creator or whatever. She acknowledged how she changed as a person and an author.

Um… hoopy frood? Definition, please. Cuz I’m lost.

Stolen from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — which I still need to get around to actually reading. The most common definition is “someone who knows where their towel is at,” but which I generally grok to mean a term of approval.

I don’t know whether I’d describe the people who leave Omelas as guiltless, but at minimum I completely understand them.

Perhaps they did not rescue the child because they were utterly powerless to do so — if they took the child from his/her prison into the sunlight, the other citizens of Omelas would simply punish them and return the child to the basement. Perhaps they did not rescue the child because doing so would necessitate violence, and they could not guarantee that provoking a civil war was morally superior to letting the child suffer. Perhaps they felt they did not have the right to break the laws of their homeland, even though they acknowledged these laws as unjust.

If I were to “rescue the child” in real life, it would involve doing things that society at large tends to describe as terrorism: burning down abortion clinics, stealing animals from fur farms. Is that really what you want of me? Or do you prefer my current style of resistance, which focuses on mere non-participation in the evil?

In regards to your third paragraph, couldn’t one argue that the Civil War was fought to literally “save the child?” In England, Wilberforce was able to change hearts and make slavery illegal without violence, but that wasn’t the case here in the U.S. I don’t think every fight for freedom and justice involves violence. MLK and Gandhi would say there was another way.

Ultimately, we can’t walk away from Omelas because sin permeates every atom of our existence. You can buy fair trade coffee, conflict-free diamonds, and clothing that wasn’t made in a sweatshop, but there will always be something else that you own or participate in that comes at the expense of another (seriously, the simplest things. Google Chinese garlic). That’s why we have to be the fourth type as the people of God. We are to seek justice, even as we acknowledge that it will never truly happen here in this world.

This is all very thought-provoking. I’m going to find this story and read it in full.

When you read it, maybe try reading the last paragraph aloud and noticing that the meaning changes subtly depending on what word in the last sentence you put the emphasis on

From what I understand of the story, (or at least, how I see it used) is to comment on society’s ills. Consider cases where human trafficking or child slavery might be used in the manufacturing of certain goods, and then sold overseas to countries like ours. In that way, we would be profiting off of people’s suffering, even if we don’t know, and sometimes even the people that know don’t do anything about it. Part of the solution, in that case, would be to ‘walk away’ by only buying products from companies that ensure no human trafficking or child slavery is involved in their manufacturing process.

That was the parallel presented to me when I first heard of this story, anyway.

I actually think Jesus’s response is to join the child in suffering and call his followers to do the same. We’d rather be rescuers, though; or revolutionaries, overthrowing an unjust system.

Also, although I haven’t read the story (though I’ve heard a lot about it), I wonder if it should be read not so much as suggesting that we should choose one option over another, but as a critique of how societies function: that whether we want to admit it or not, we always go with one of these two choices (be complicit or walk away). We’re incapable of doing anything else. Maybe I’m just interpreting this in the light of my own beliefs about universal sinfulness; but from my reading of LeGuin’s other work, she often seems closer to the Christian perspective on this than many other secular authors.

Thank you for writing this! I’m glad to see more engagement on Speculative Faith with secular SF/F writing, especially the stories that are most deeply concerned with questions of morality and ethics.

If a person is drowning, then other people joining that person in drowning does not help that person one bit. God the Son did come to earth, born of a virgin, and lived as a man, and also suffered and was tempted as we are, but not so that he could drown and die in sin like us, but to rescue us from the sin that had us dead and by his own sacrificial death wash away our sins and make us alive.

” I wonder if it should be read not so much as suggesting that we should choose one option over another, but as a critique of how societies function”

Your comment, in my opinion, shows a much better understanding of the story than the review does, Kristin. Le Guin lays on each of us the burden of selecting an option for what to do about the symbolic child’s misery, no matter what anyone else says. At the end of the story, the narrator admits to having has no idea where the ones who walk away from Omelas are going, or even if it exists.

“But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.”

A Christian might take that as hearing the voice of God.

And by the way, if you still haven’t read it, it’s on line. You can google it.

This review, like a lot of them, makes the mistake of treating the story as conventional fiction, i.e. counter factual history. In fact, Le Guin tells us clearly in her introduction that it is a psych myth.

Walking away from Omelas, in this psycho myth, doesn’t imply physically leaving any real or imagined place or otherwise giving up. It implies a mental freeing from the lies told by the narrator (who clearly isn’t Le Guin but a psycho mythical figure like the child). And it implies taking action. The narrator has no clue what the action is, but is aware that they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.

Google tells me that the concept of “psychomyth” is referring to a specific idea, but in a sense, doesn’t most fiction function as psychomyth? “In such a situation, people would behave thus,” with flavors assembled by our cultural/individual ideas of how people do/are supposed to behave?

Replying three years later.

Yes it is possible that most fiction can function as psychomyth in addition to its counterfactural history role. But The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas is nothing but psychomyth.

Replying to myself five years later.

Dear Greg,

You’re wrong about at least one thing. She doesn’t even imply taking action.

Other than in the introduction where she calls it a “psychopath” (whatever that means) and refers to the concept of the scapegoat, the only time to my knowledge she ever said anything about its meaning was in 2016 in a note to me. I wrote her saying that, when I read it aloud, the meaning changes depending on which word in the first cause of the last sentence (“But they seem to know where they are going”) I put the emphasis on and asking her which one she intended.

I’ve got her note back to me hanging on my wall. She said, “the point is you CAN keep reading it in different ways.”

You should try reading the last two sentences aloud 10 times with an emphasis on a different word in that clause. You might learn something.

Greg

I meant “psychomyth,” not “psychopath.”

What people are missing here is that the short story is actually a satire on our Pharisee-level power to look gift horses in the mouth. Le Guin occasionally pauses her description of the utopia to let the audience know that she’s not setting you for a twist, or delusional, or even drunk: the place really is that good. It is only near the end when she relents and gives that tragic twist you were clamouring for this whole, complete with a “There! You happy now!?!” moment. Kinda like how Jesus came to save the Jews, only to be branded a heretic.

Interesting interpretation, but taken that way it’s a super weird departure from her style in the rest of her work. She’s done unreliable narrators, like in The Left Hand of Darkness or Daughter of Odrin (I did at one point pull through on my good intentions to read more Le Guin). I would say her style involves irony, but not really satire.