‘The Maze Runner’ Chases A Hope Unseen

One of the strengths of post-apocalyptic fiction is that it provides villains with a playground in which nearly any curtailment of liberty can be reasonably justified. No longer a merely theoretical specter, the next End of the World (because the apocalypse never runs an effective mop-up operation) now looms as the ultimate bogyman — the de facto raison d’être for whichever institution manages to consolidate humanity’s remnant under a totalitarian thumb. As storytelling formulas go, it’s an efficient means by which societal tensions between liberty and security can be extrapolated into a spectacle stripped of mitigating factors and dislocated from the incrementalism that tends to gum up contemporary political thought.

The Maze Runner (2014), based on the 2007 YA novel by James Dashner, stands out from this genre in part because of its layering. The parameters of its setting and mechanics of its plot work to trap its characters inside a restrictive world-within-a-world, allowing them to play out their own petty doomsday politics in microcosm of whoever it was that marooned them in the Maze. Any community, no matter how small, will be tempted to squelch individual freedom for the sake of the greater good. And, as the heroes and villains within the film’s ensemble cast demonstrate, the battle between comfortable security and dangerous liberty is one waged within every human soul.

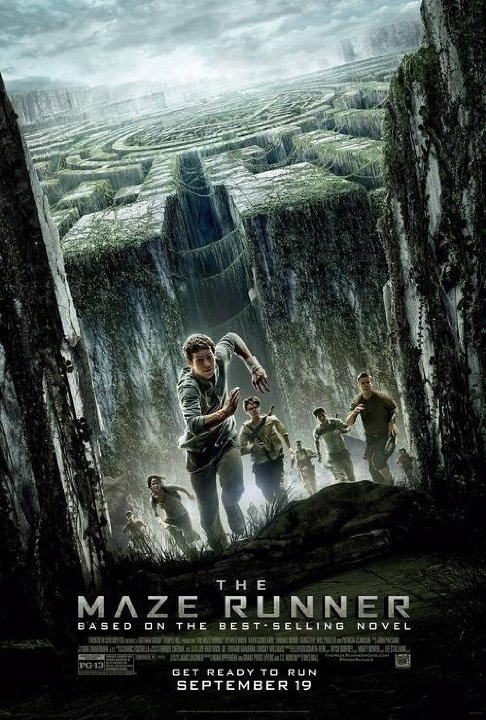

The Maze itself dominates this story. It’s a compelling milieu and a titanic feat of engineering: an ever-changing labyrinth of sheer, several-hundred-foot-high concrete walls which ring the Glade, an oasis of relative normalcy. No one trapped within the Maze knows who built it or why, or even what’s outside. Their memories have been wiped. All they know is that to remain in its shadowed canyons after its door shuts at nightfall means certain death in the jaws of its ravenous guardians, the Greavers. Inscrutable, omnipresent, ever-brooding — the Maze chews scenery from beginning to end. It functions like a character and gets treated like one by first-time feature director Wes Ball. You’ll find yourself eyeing it warily over characters’ shoulders, wondering whether you trust it enough to look away.

With that said, however, this film isn’t about the setting; it’s about a teenager named Thomas (Dylan O’Brien channelling a young Christian Bale) through whose eyes the story is told, and whose coming is “like the falling of a small stone that starts an avalanche in the mountains.” He awakens in a speeding elevator with no memory and no possessions beyond the shirt on his back. When the grate slams open onto the floor of the Glade, he’s welcomed as a “Greenie” into a self-sustaining community of young male survivors whose existence is defined by their boundaries and for whom curiosity constitutes a crime. No sheeple these: they’re intelligent, resourceful, industrious, and very afraid — likely due to natural selection more than anything else. Whatever escape plan you’re imagining at this moment, they’ve already tried. Whatever brilliant notion just occurred to you, they thought up and discarded long ago. And they’ll do whatever it takes to protect their community from repeating past mistakes.

Enter Thomas, a guy who wants out. He’s unimpressed with time-honored tradition, uninterested in playing by the rules, and unafraid of well-meant warnings. One of the great joys of this story is found in the competency of its characters: such a high baseline allows the focus to shift from mere personality-conflict to the ideas that drive characters to act. Thomas is just as competent as the others, but he’s far more compelled by the mental echo of a freedom he can’t quite remember than by the prospect of eking out a guaranteed survival within his new confines. He’s drawn by hope, not driven by fear. And it is this essential optimism, this irrepressible desire to apprehend an unseen expectation long since despaired of by others, that carries both him and his companions beyond the limitations imposed by conventional wisdom and into a perilous new world.

This film works on so many levels precisely because it feels so personal, so intimate. The cinematography, editing, and sound design force the viewer into Thomas’ headspace. We see what he sees, hear what he hears, feel what he feels. Every beat is played out for all it’s worth. At its heart, The Maze Runner is less special-effects extravaganza than tautly-constructed character study. The precipitous ramparts that circumscribe the world simply aren’t imposing enough to overshadow Thomas’ perseverance, Alby’s (Aml Ameen) solemnity, Newt’s (Thomas Brodie-Sangster) humility, Minho’s (Ki Hong Lee) courage, or Chuck’s (Blake Cooper) friendship. The plot is so solid that the characters, unneeded as devices, are freed up to breathe and behave like real people in defiance of Hollywood convention — from key moments of surprising-competency-that-really-shouldn’t-have-been-so-surprising, to subtle little expectation-subversions like timely communication between characters (gasp!), or a character’s abortive attempt to start a chant in an uptight crowd. As viewers, we’re given more than a destination; we’re given companions for our journey. And we’ll need them, for this journey’s no stroll in a glade. Together, these young men, along with a mysterious young woman — Teresa (Kaya Scodelario) — must confront both the inertial weight of tradition and those nightmares which stalk the unknown.

And they are nightmarish.

The Maze Runner pushes the limits of the PG-13 rating. Targeted at children it is not. The violence is brutal, unrelenting, and often freakish, the tension neigh unbearable. What begins as an intriguing amalgam of Lost, Lord of the Flies, and The Hunger Games has by the end become a terrifying cat-and-mouse struggle of man-versus-nature and man-versus-man. The convictions of its characters will be put to the ultimate test. The certainty of Thomas that there is more to life than walls may lead everyone he loves straight down a dead end. And, in the uncertainty of the Maze, those who choose to run its courses will come face-to-face with the kind of liberty that walks hand-in-hand with death.

Whether the risk is warranted depends entirely upon the nature of a world beyond their sight.

It sounds like a good film with bad timing. Just it’s luck to catch the far edge of the fading YA dystopia trend. I’ll check it out once it hits home video.

I definitely recommend it be seen on the big screen. I saw it in a Regal RPX theater with Dolby Atmos sound, and it was worth every additional penny. This is one of those times when it pays to abandon one’s hipster tendencies, pretend ignorance of prevailing fads, and slip in amongst the lemmings to see what all the fuss is about.