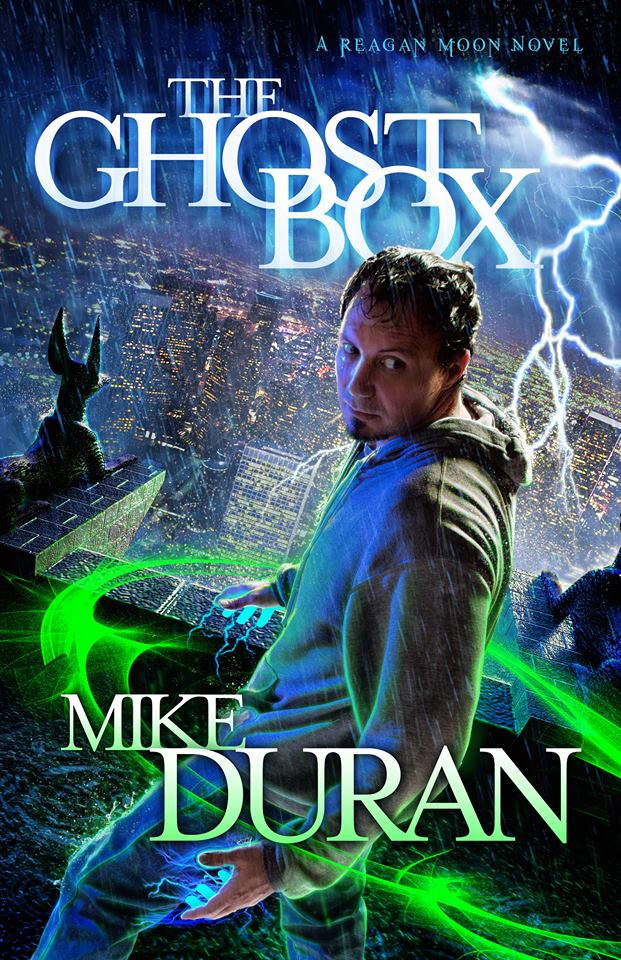

‘The Ghost Box’ and The Spirit Sea

“As much as people want to blow off the paranormal, part of us simply cannot peel our eyes away.”

It is this sentiment, burning at the heart of The Ghost Box by Mike Duran, that unifies a narrative at once gripping, unsettling, and uneven. It’s a theme only stoked by in-world skepticism, a thought fanned into flame by rising gusts of the supernatural: that all human beings harbor a hunger for the unseen. It’s this hunger that’s kept our protagonist fed: as a reporter for a paranormal tabloid, the man named Reagan Moon is financially dependent upon an invisible world, though he himself doesn’t believe it exists beyond people’s heads. But the time has come when looking on will no longer be enough.

The Ghost Box is a paranormal thriller in the vein of That Hideous Strength and The Apocalypse Door. Like those novels, it starts out small — a rumor here, an industrial accident there — and slowly ramps up until the world itself hangs in the balance. But, despite its religious imagery and eschatological overtones, this novel is about as “Christian” as Hellboy. As a kind of stylistically-superior version of Ted Dekker’s Saint, Duran’s story ignores the major players one expects to meet on the spiritual plane: here, God, Jesus, and Satan are notably absent. And yet the vacuum they leave teems with a menagerie of minions — angelic mimes, vampiric aliens, shapeshifting action girls, and transdimensional Eldritch Horrors. And in the midst of it all is Reagan Moon, a jaded journalist nursing doubts over his girlfriend’s death and sneering at the credulity of his own reader-base. As a child he dreamt of fighting evil, of throwing in with the side of light in a field of cosmic conflict, but not anymore. Not since loss dimmed the light in his eyes. Not since he became a rationalist.

Little does he realize the conflict is about to find him.

The tale begins in true hard-boiled fashion, with the arrival of a mysterious client on the doorstep of Reagan’s shabby LA apartment. Our hero’s breezy sardonicism is immediately appealing and deftly dispensed in unbroken first-person by Duran, who manages to keep his protagonist’s angst just this side of irritating. Following a series of strange encounters and truly cringe-worthy metaphors (“the chasm it left inside me made the Mariana Trench look like a puddle”; “he was … barreling down on all of us like a runaway semi with a cargo of nukes”), along with a few really good ones (“flashing 100 dollar bills in this neighborhood was like chumming for sharks with a side of beef”), Reagan Moon is confronted with the disturbing possibility that Ellie, his allegedly deceased girlfriend, may not be quite so deceased as all that.

But now that you’re imagining a standard-issue ghost story, let me assure you that’s not what this is. For one thing, there are no hauntings, disembodied voices, or things going bump in the night. For another, the intel Reagan receives indicates that Ellie’s being “harvested” somehow.

Oh, it is so on.

Over the next seventy-two hours, Reagan plunges headfirst into a reality wilder and more chaotic than any he’s heretofore known. Aided by a powerful talisman, a cryptic mentor, and a pair of goggles that allow their wearer, Elisha-like, to pierce the veil between this realm and the next, Reagan must reevaluate all that he’s summarily dismissed. A spiritual sea — preexistent, pervasive — floods in upon his senses as though he’s a submariner who’s spent a lifetime avoiding portholes.

Having taken his first steps into a larger world, Reagan now finds it impossible to reenter the status quo. But what pumps life into LA’s grimy alleyways and sun-baked subdivisions, newly alive with the spirit-world flora that presses upon them unseen, isn’t some overwrought sense of grandiosity or flair, but simple specificity in description. The world of Reagan Moon, unlike the spiritual realm into which he’s been thrust, is easily visualizable.

Duran never misses a chance to leverage his settings for sensory immersion and emotional impact. His writing has the kind of immediacy found only in the reek of oil and radiator fluid as combatants roll on a rain-slick curb and dodge oncoming traffic, or in the tinkling of a water fountain as a man creeps through late-afternoon shade toward a freshly-skewered corpse. No matter where Reagan Moon ventures, we are fully there.

Unfortunately, Reagan himself has a tendency to be a bit of a homebody when it comes to his cognitive life. He retreads the same plot of mental turf ad nauseam: constantly reestablishing his grievances, retelling his personal history, and re-reflecting on his state of being. Perhaps it’s the fact that the first-person perspective just doesn’t allow us to escape from his head, but there were times — especially toward the end, ironically — where I, perhaps unfairly, found myself despising Reagan for his passivity in the same way I despise Fitzgerald’s narrator in The Great Gatsby: because his thoughts so outnumbered his actions.

Equally annoying was Reagan’s madly-monologuing adversary. During the climactic showdown I thought the Big Bad was trying to talk him to death. I mean, don’t get me wrong: it was all very fascinating — what with the large-scale strategic revelations, the introspective reflections on history recent and ancient, and the “oh, didn’t you know?” psychological heckling — but for each verbal threat leveled against our hero, a spring popped in my disbelief-suspension. We know you want Reagan dead or worse, I kept thinking, so just attack already! It was the sole scene in the story where I felt the plot had enslaved the characters, but man, was it a doozy.

Alright, enough with the negativity. Despite the hiccups, I really did love this novel. Its visual substance and imaginative scope will, together with the reluctant pluck of its protagonist, transport you to a world horrifyingly alien, yet even more horrifyingly familiar. Reagan Moon may start out as a washed-up cynic who talks to himself too much, but he has the vulnerability to admit when he’s been wrong about the world, and also the love to fight for it with everything he has left, though that’s likely insufficient. Faith has never been easy for him, and no more so than when he at last believes.

It’s easy to say “I’ll believe it when I see it,” but of those to whom such grace is given, much is in turn required. That’s the catch to perceiving the invisible: there’s simply no room for nominal belief. Duran knows this. In the end, it’s not the opening of Reagan Moon’s eyes that matters most, but the movement of his feet.

Could it be said of you or I that we move in light of what’s invisible?

I really enjoyed the book, too. It falls a bit short of the Dresden files–Reagan is kind of whiny–but then I started thinking of it as an origin story. All heroes are whiny brats when they first get their powers–they don’t become awesome until later. Dresden starts out awesome, and you don’t get his origin story until flashbacks in book 12. So I think book 2 of Reagan Moon, when he is using his powers to fight evil, will be properly awesome.

I’ve heard criticisms such as “whiny” and “passive” used for really intellectual, over-thinking heroes/heroines. I find it interesting. I don’t tend to have the same criticisms (generally) because I think it’s good characterization. But, then, there are spot-on characters I don’t like being in the heads of for entire books–usually self-centered narcissists. So maybe it’s a personal tolerance level for certain personality types. I mean, yeah, a character should grow throughout the story, but not in a way that is at odds with his personality.

Kessie, I got the same impression. Reagan’s confidence is a derivative of his sense of purpose, and he doesn’t really internalize the latter until the last possible moment. That’s a huge internal journey for anyone, but it’s one with which I, able to see the result coming ten miles out, tend to grow swiftly impatient.

Like Unbreakable or Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood, this story ends just as it starts to get interesting. But, unlike with those films, here I get the sense that sequels are forthcoming. So I’m okay with that.

Jill, I think the factor that determines whether or not I find a character’s introspection “whiny” is whether said character has the ability do anything about that which occupies his or her thoughts. So if a man is courting a woman and constantly second-guessing his strategy, I don’t consider it whiny (I’d probably consider it humorous). But if he’s obsessing over the woman without ever making a move, it won’t take me long to start despising him. Real life has enough timidity and indecision; I find it annoying enough there as it is.

Which is why some of the best writing advice I’ve ever received was, “Never let your character do nothing. Always have him doing something, even if it’s the wrong thing.” And I think Reagan Moon’s pretty good at adhering to this rule, so I can’t fault him too badly.