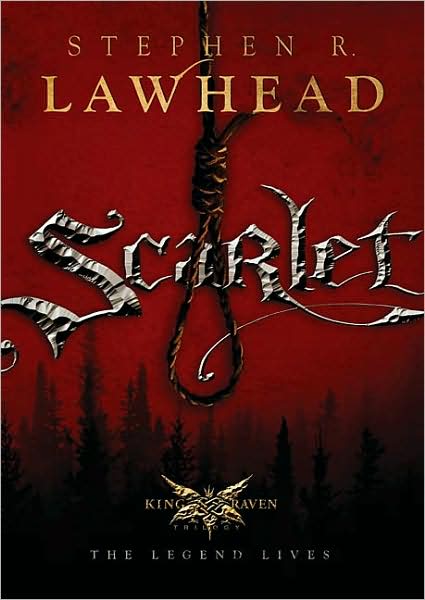

‘Scarlet’ Makes Legend Merry Again

When Will Scarlet’s thane was exiled to Daneland, the king took his land. Deprived of his home, and his living, and his community, Will sought refuge in the forest. But the English crown laid claim to the forests, too. After being left hungry when the king destroyed his old home, Will was forbidden under penalty of death to satisfy his hunger with the king’s deer.

When Will Scarlet’s thane was exiled to Daneland, the king took his land. Deprived of his home, and his living, and his community, Will sought refuge in the forest. But the English crown laid claim to the forests, too. After being left hungry when the king destroyed his old home, Will was forbidden under penalty of death to satisfy his hunger with the king’s deer.

This is what is called being “between a rock and a hard place.”

Hearing rumors of the Raven Hood, Will traveled to Wales to find him. And there, in the ancient forest, Will Scarlet joined the band of outcasts who lived by capital offenses against the crown.

This is what is called “out of the frying pan and into the fire.”

Scarlet is the second book of the King Raven Trilogy, following Hood and upping the overall quality of the series. Despite my disappointment with Hood, I was interested enough to open the second book. It began in the first person, as Will Scarlet gave his confession to a priest in a dungeon. By the end of the first chapter, I was ready to read the book all 450 pages through.

Scarlet is divided into three general styles. The dungeon scenes are written in first person and the present tense. When Will relates his story to the priest, it remains first-person, but the tense becomes past. In addition, Will’s account is interspersed with chapters written from Lawhead’s usual omniscient viewpoint. This is not an ideal story structure, with a little too much complexity and not quite enough consistency. But ultimately it works.

And it gives us Will’s narrative. The first-person style is remarkably well-done, with a distinct and appropriate tone. Will Scarlet shines brightly through, a sympathetic and charming character. He is at once cheerful and fatalistic, once saying, “Well, that’s Will Scarlet for you – doomed beginning and end. Oh, but shed him no tears – he had himself a grand time between.”

Through Will Scarlet the King Raven Trilogy gets, at last, a measure of the merriness of the Robin Hood legend. Bran himself is more likable than in the book called after his name. This is partially because he is seen, for much of the book, from Will’s viewpoint – with that perspective and that distance. But it is also because Bran, having finally taken up his responsibility, shows a better side. A flawed hero he may be – but a hero.

The villains, too, come into their own. Count Falkes, who never had the heart to be a truly great villain, is increasingly supplanted by worse men. The sheriff, here introduced, is a far more vicious and more dangerous enemy.

The deep historical milieu remains the same. Scarlet’s pace is quicker and its plot more interesting than Hood’s. The story droops a little in the third act, but it ends in a powerfully-done cliffhanger.

Religion is a very present element of Scarlet, as it was of that time and place. In the King Raven Trilogy, as in old Robin Hood ballads, God is invoked by villains and heroes alike. Stephen Lawhead is, I think, realistic in writing a bishop concerned only with worldly wealth and power. Yet there is genuine religion in the book, and help as well as harm in the church.

Scarlet is more history than myth. At the same time, a mystical element roosts in unexpected corners of the story. This is not so much a re-telling of the Robin Hood story as a transformation of it. Complex, beautifully written, and filled to the brim, Scarlet is a worthwhile read.

I agree, it was definitely the best book of the series! 🙂

One of the reasons Scarlet is better is, I think, Will’s first-person narrative. For a writer who loves the old-fashioned, omniscient style, Stephen Lawhead can do first-person surprisingly well.