95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation, part 3

Here’s the article of this series voted least likely to become clickbait. That’s because, unlike the first two articles in this series about reforming Christian fiction, this article emphasizes what’s right about Christian fiction. Yes, by that, I mean today’s industry, today’s beliefs, today’s books right there on those cheesy Christian bookstore shelves right now.

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther didn’t set out to split the Church. He wanted to reform it. And reformation proper means to keep what works while throwing out what doesn’t. In Luther’s case, it wasn’t just abuse he wanted gone, but unbiblical teaching.

However, if we don’t affirm what’s right with some thing, we can’t expect people to listen when we criticize what’s wrong with some thing. This applies whether the thing is the capital-C Church (all of God’s people organized to glorify Him), or a local church, or the fiction-making industries run by Christians.

Be sure to read the complete series, 95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation:

- The purpose of Christian-made stories,

- What’s wrong with Christian-made stories,

- What’s right with Christian-made stories,

- How Christian readers can reform these stories in the future.

Part 3: What’s right with Christian-made stories

Part 3: What’s right with Christian-made stories

- Christian-made stories are often labeled as being made by Christians. In a world with popular culture shared by all people, yet in which every cultural “group” has its own cultural works to enjoy, having uniquely labeled “Christian” works can be very helpful.

- Many Christian novels affirm that God, not man, is Creator of our world and morality.

- Many Christian novels specifically and naturally affirm the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

- Many Christian novels assume the basic necessity of God’s people, the Church, made of local churches whose members preach and live according to the Gospel in the world.

- By having fiction at all, Christians prove we don’t believe man can live by dutiful work or spiritual activities alone. Deep down, we all rightly suspect that God has made us not only to labor six days every week, but to “rest” creatively for Sabbaths of recreation.

Christian novels span a variety of common genres—including some fantasy and science fiction—and have created new genres, such as Amish romance and end-times thrillers.

Christian novels span a variety of common genres—including some fantasy and science fiction—and have created new genres, such as Amish romance and end-times thrillers.- Even secular culture has caught up to modern Christian tropes, such as the Rapture.

- Christian fiction may include great characters, original plots, and unique style.

- Christian fiction may show the world truthfully. Many novels explore topics that secular creators declare “unclean,” such as sin’s results. Even “clean” stories remind us that people do exist who don’t swear or fornicate, either out of tradition or love for Jesus.

- Really great Christian novels inherit a tradition of showing the absolute victory of God over evil—making evil look very powerful so that we can rightly see God as superior.

- Some Christian stories explore the fact that “moral relativism” is comically absurd.

- Some novels explicitly test moralistic or prosperity “gospels” and show how they fail.

- Quite a few Christian novels have intentionally explored issues relating to social justice, including not only abortion but racism and discrimination. Others overtly challenge the myths Christians may have in the west, such as confusing their nation with the Church.

- Some Christian novels don’t make their highest purpose to evangelize the non-Christian reader.

- In fact, these novels can be made by Christians, for Christians, with lesser appeal for the casual reader—again, like any ethnic or cultural group has “their own” creative works.

- The Christian obsession with prophecy or “end times” novel series has, for now, ended.

- Some Christian novels, even if they are not in speculative or “fantastical” genres, affirm a supernatural worldview, that is, a realistic worldview. Even in small ways these novels assume God exists and works providentially, or even miraculously, in the world.

- Modern Christian fantasy may struggle to find its audience, but Christians can still boast “our people’s” legacy of popular fantasy authors, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis.

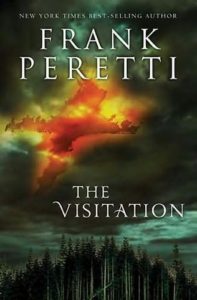

We also have Frank Peretti, who succeeded by writing explicitly about Christian ideas.

We also have Frank Peretti, who succeeded by writing explicitly about Christian ideas.- The most popular authors, past and present, aren’t pastors or spiritual leaders who try to “write” novels (often with help) in their spare time; they’re actual Christian novelists.

- Bless their hearts, but many Christian novels do try to explore cultures and individuals who are different from modern American Christians. For example, some novels really like exploring Amish culture, or a reasonable facsimile of it. But seriously, it’s a start.

-

For example, this work of Christian fiction was popular last Christmas.

Christian romance may outsell Christian fantasy. But we do have other popular fiction genres, such as mysteries. (We also have prophetic speculation and Heaven speculation. Yes, that’s a backhanded compliment. Evangelical imagination is alive and well, often to an unbiblical fault. Our secondary problem there is the mislabeling of genres.)

- By now we may reasonably suspect that even older Christians, who support the above-mentioned genres, aren’t really that opposed to fantasy. They just don’t like it as much themselves. Or they may be like younger Christians, and get their fantasy fix elsewhere.

- Growing numbers of young Christians don’t want traditional genres. We want fantasy!

- The decline of traditional Christian bookstores reveals a potential shakeup in Christian fiction, perhaps one to build on today’s publishing structure for a Christian Fiction 2.0.

We’ll wrap this series next week with part 4: How can readers reform Christian fiction?