Tips For Good Allegory

Is allegory dead? Are people still writing it? Okay, never mind, I know people are writing it, but are there any good ones anymore? Good allegories only seem to come out once a generation, but why are there so many pretenders scratching out half-baked stories that flop in a flash?

Is allegory dead? Are people still writing it? Okay, never mind, I know people are writing it, but are there any good ones anymore? Good allegories only seem to come out once a generation, but why are there so many pretenders scratching out half-baked stories that flop in a flash?

I’ll wager a guess: it’s a good allegory, but a bad book. Many Christian writers think a good message will stand on its own, and maybe it used to, but that won’t fly today. Readers don’t want to buy sermons—or if they do, they won’t go to the fiction section! Fiction readers want to read books. Stories, tales, yarns that you’ve spun.

But stories have rules. So if you’ve ever even entertained the idea of writing an allegory, consider the following suggestions.

- Throw out the Bible

Stay with me, put down that pitchfork. I mean in a narrative sense. Themes, topics, characters, all these Bible facets are welcome in allegory, so long as you keep them far, far away.

By this, I mean don’t cut and paste, or do so as little as possible. I once edited a story where the scene follows a non-Jesus character who is totally Jesus because he’s literally saying and doing every single thing Jesus said and did in the order he did it. That’s not allegory. That’s a lawsuit from Zondervan!

Allegory takes things and expounds upon them in a new way, or arranged in a new order. They don’t just give us what the Bible has already said—there’d be no point. If you want people to read the Bible word-for-word continuously, just give them a Bible.

Fiction is about creating.

- Forget about Jesus (as you know him)

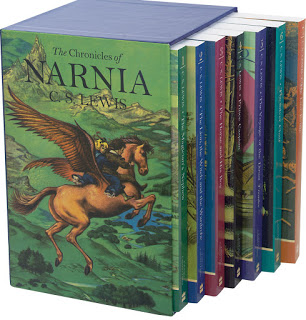

Do you know why Aslan worked so well? Because C.S. Lewis didn’t see him as allegorical. In A Life Observed, biographer Devin Brown reports that Lewis didn’t say, “This is Jesus;” he said, “This is what Jesus would say and do if he were Aslan.” He made Aslan a character that existed in his own world.

Do you know why Aslan worked so well? Because C.S. Lewis didn’t see him as allegorical. In A Life Observed, biographer Devin Brown reports that Lewis didn’t say, “This is Jesus;” he said, “This is what Jesus would say and do if he were Aslan.” He made Aslan a character that existed in his own world.

If you’re dropping Jesus in your story, he’d better literally be Jesus, not some representation, but Jesus himself. If it’s a representation, then it has to act like a representation.

If your Jesus figure (or whomever) wasn’t merely an allegorical element, how would he act?

- Subtlety, even in Overt-ness

I don’t like coffee at all, but douse it in enough sugar and flavoring, and I might drink it. The same goes for allegories. To most, it’s a bit hard to swallow, but drown it in another flavor, and they won’t even realize they’re taking their medicine.

Take another leaf from Narnia’s book. When Aslan died and rose again, it was an extremely obvious parallel to the cross. But you know what the book never said? That it was an extremely obvious parallel to the cross. It let the moment be and rest on the laurels of its own world.

The book never turned to the reader and said, “This is for you! It’s the same in real life!” Lewis kept the act about Edmund and Aslan. It didn’t even preach a salvation message to its own inhabitants. One might say that nobody is really “saved” by Aslan’s death except Edmund. But it’s okay.

Why? Because the readers got it.

- Give your readers credit

When you’re writing to adults, remember this: adults can feed themselves. Just give them the food and they can take it from there.

Don’t fret over the message of your allegory, fret over the writing. Messages are easy to make, but hard to deliver. The more it’s a story and the less it’s a message, the better the odds are your readers will love it.

Writers must be excellent actors when they write allegory. This isn’t church; it’s a novel. There’s no place for an alter call or a desperate plea for salvation thinly veiled as narrative. Even Christian readers get sick of poor pretenders. So you must sell your allegory under the guise of a planned, logical, meaningful story, even if that “story” is thin.

For example, Hind’s Feet on High Places isn’t fooling anybody, not when the main character’s name is Much-Afraid. But though it’s overt as can be, it never looks at the reader and says, “Get it?” It just tells the story of how Much-Afraid grows and changes on her journey, and trusts the reader to bridge the gap from book to life.

Subtlety is an art. Writing is an art. If you want to write allegory, you must be, or become, an artist yourself. This takes a lot of work and a lot of failure, but those things make you a more successful writer, one whose messages are more likely to be heard by the masses.

In short, try to forget what you’re writing is an allegory. Think of it as a story and weave the tale around the allegory so tight that your readers won’t know what hit them.

– – – – –

Michael A. Blaylock is a writer, editor, Christian, gamer, reader, film buff, and anime nerd living in Southern Idaho. Passionate about art in all forms, he creates to show God as artist and promote Christian freedom. He’s the author of Ferryman and several shorter projects. Find him on Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, and his website.

Great tips! Thanks Mike

No Prob!

Thank you. I will admit that thinly-veiled allegory is one of the reasons Christian fantasy so often makes me cringe. And it’s not only Jesus as an allegorical figure – how about the fantasy religious system which is basically the Christian church (as the “good” religion) or the Catholic Church (the “bad” guys – all that legalism and idol worship, bad priests, etc). Ugh. I get that this is tricky for us Christians who write fantasy, and it’s one of the reasons why my own fantasy is set in a actual historical period so I didn’t have to make up my own religious system.

Yes I love allegory