Death is the great universal fact of life, as universal as birth. It rings down the curtain on every human play, sends everyone home in the end. We all know this; we are all overshadowed by what G.K. Chesterton called the last impossibility. It’s curious that we don’t take death more seriously than we do. Our popular culture overflows with glib platitudes, all catalogued in our books and movies.

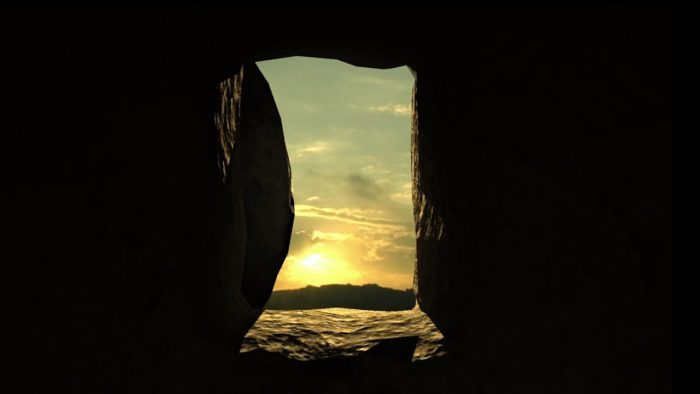

You know the platitudes. He lives in your heart. She lives in your memory. The departed is – well, take your pick:  inside you, inside all of us, around us, in the love or legacy or memory she left behind. The dead are anywhere but gone. Our culture, as manifested in popular books and movies, does not look to the blazing dawn of the first Easter, but usually it is equally unwilling to look at the cold finality and ultimate aloneness of the body in the tomb. What we end with is a popular culture that will face neither the darkness nor the light.

inside you, inside all of us, around us, in the love or legacy or memory she left behind. The dead are anywhere but gone. Our culture, as manifested in popular books and movies, does not look to the blazing dawn of the first Easter, but usually it is equally unwilling to look at the cold finality and ultimate aloneness of the body in the tomb. What we end with is a popular culture that will face neither the darkness nor the light.

I would not recommend, as a curative, that every instance of death in our fiction be expanded to contain the fullness of Christian doctrine on the subject. There is certainly no reason to constantly elide the Resurrection; its riches are too rarely mined, even among Christians. But not every story has space for the doctrine or the riches, and such things are not to be forced. I wouldn’t ask that every story with death be a story about Easter. But I would like to see more books and movies get beyond the standard Hollywood cant.

It is possible to catch some rays of light, to hint at hope or even just mystery. J.R.R. Tolkien hinted at hope when Aragorn, in the face of death, offered this consolation: “In sorrow we must go, but not in despair.” Not that we need such exalted contexts as Lord of the Rings to find the hope and the mystery; they are possible everywhere. Emily Blunt’s “Where the Lost Things Go” dreams of an unknown place, maybe behind the moon, where lost things might be found. Gone, yes, the song concedes, but gone where? – and that hard question is more comforting than the glib answers.

If a story is not to have the light, I would take even a measure of darkness over artificiality. Honest sadness is better than false comfort. I’ve heard the cliches so many times that all I can think, when a book or movie trots them out again, is that nobody wants the people they love to be Inside Of Them. The greatness of love is that it gets you outside of yourself, that it brings you into contact with another soul in this huge universe. No one wants a memory, an image, an echo. It’s not the same and it’s not enough. We want a real, living person.

We don’t need courage to face the darkness. We need hope. Christ’s Resurrection teaches us that death is not to be accepted or dreaded. As we absorb that reality into our hearts, so may it be reflected in our stories. We are not to be driven to the pale ghosts that haunt our hearts for comfort, nor must we pretend that death is not hideous. For Death is an enemy, but a conquered enemy.

Interesting. There’s a little bit of truth in the ‘he lives in you/your memories’ part, as I’m starting to realize. Not in a literal way, but sometimes reminiscing about a parson can almost make it feel like they’re still there. That said, people use that saying so much that it feels shallow, annoying and fake much of the time.

I don’t usually like using that saying myself, in or out of a story. But I do have chars delve into their memories and reminisce over the dead, both for better and for worse. Like…in my Naruto fanfic, one char will use genjutsus (illusions) to reminisce about his dead ex girlfriend, which kind of helps him cope day to day, especially since he doesn’t want to forget her, but it also makes it harder for him to move on in some ways.

Other than that…I dunno. Death is depicted as upsetting, and something that people try to prevent with everything in them. And part of the reason it upsets them is because that person is gone and inaccessible regardless of any afterlife.

Yes. At least for a while they are no more.

We have no idea where, when or how we’ll meet again.

That’s why even faithful Christians mourn the dead.

Thanks for sharing Shannon. For years I’ve built a lens for viewing the world in two general camps: those who believe in life after death, and those who do not. If you believe there is a greater power at the wheel of the universe and that there is more than our temporal, physical body’s life on the planet, then you can live and operate from a place of hope. Things will go wrong, but there is a restoration that will come. If, however, you believe that this life is all there is, flip the switch, lights out, worms and such, then this life literally is all there is, so everything that happens here matters (because after you die, it doesn’t).

Maybe I need to start broadening that into “Those worldviews that believe death matters” and “Those who gloss it away”. At least in the above case, death matters. For one group, it’s the turning the page on the Great Story. For the other, it represents finality and gives the rest of one’s life meaning. In the gray area you describe, there’s really little of either.

One of my pet peeves about pop culture stories is that so few people grieve. A person dies and the rest of the cast moves on as if nothing monumental happened or has changed for the people left behind. So, I really appreciate this post, Shannon. Christian writers should have a different approach!

Becky

That’s sort of what I like about anime. A lot of times, at least with the well made ones, the characters have strong bonds and it’s actually a big deal when one of them dies. There’s grief and mourning that often has major plot implications later on.

I think this is why the “grimdark” genre is gaining a following. At least it’s honest about the ugliness we see around us.