The Decision of Meaning

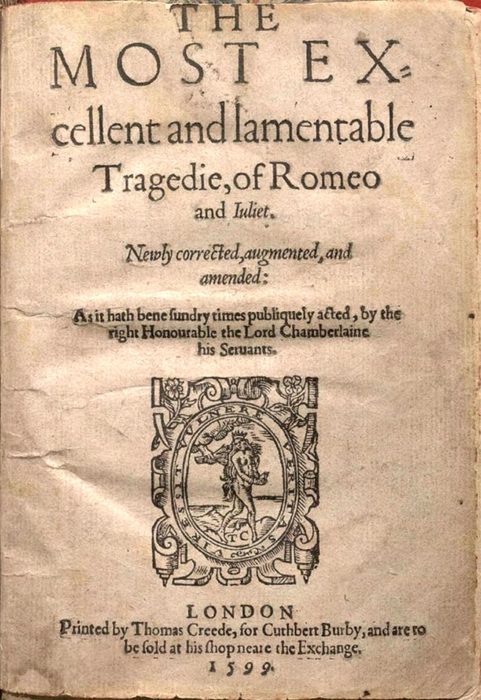

The happiest person in Romeo and Juliet is Rosaline, who had the good sense to be uninvolved. Romeo spent his initial scenes declaring her matchless beauty, his undying love, that there would never be another woman for him, etc., up until he met Juliet and immediately began saying all those things about her instead. Romeo needed some sort of productive occupation. I would like to think that Shakespeare presaged Juliet with Rosaline as an ironic comment on the transitory nature of even passionate feeling. More likely he included Rosaline simply because the 1562 poem Romeus and Juliet did.

I take Rosaline to be the inheritance of an older source, thoughtlessly carried over, because she is out of place within the new work. Romeo and Juliet is not ironic in its tone. It takes itself and its lovers seriously. That Romeo replaces Rosaline as casually as people replace light bulbs undermines the love story. None of his dramatic declarations of undying love were true. He believed them, but they weren’t true. That they become true when he starts spouting them about Juliet can only be taken on faith, and some of us are skeptics. Yet I don’t think, given the tenor of the play, that we are meant to doubt.

I take Rosaline to be the inheritance of an older source, thoughtlessly carried over, because she is out of place within the new work. Romeo and Juliet is not ironic in its tone. It takes itself and its lovers seriously. That Romeo replaces Rosaline as casually as people replace light bulbs undermines the love story. None of his dramatic declarations of undying love were true. He believed them, but they weren’t true. That they become true when he starts spouting them about Juliet can only be taken on faith, and some of us are skeptics. Yet I don’t think, given the tenor of the play, that we are meant to doubt.

I also think that, whether Shakespeare intended it or not, Romeo’s histrionics over Rosaline add a grain of salt to his histrionics over Juliet. The war over authorial intent has been waged and, for the moment, decided. A story’s interpretation is not presumed to be dictated by the author’s intentions. As much as I approve, I willingly admit the merits of the defeated idea. There is a kind of fairness in giving the creator the decision in the meaning of the work. And literary interpretation could do with more objectivity. That is the inescapable conclusion of sitting in college literature courses, listening to people give suspiciously faddish interpretations of books you suspect they merely skimmed.

But although it would be the well-deserved death of a thousand lazy essays, I can’t give the decision of meaning to creators. They’re interpreting, too. The literary evolution of Romeo and Juliet proves the point. Shakespeare based his play on Arthur Brooke’s Romeus and Juliet. The story is essentially the same in both works; Shakespeare repeated Brooke in every event of importance. Yet if Shakespeare took it for a love story, Brooke took it for a morality tale. Brooke, who probably did not suffer fools, advised his readers that the “most unhappy death” of Romeus and Juliet stood as an example to them of what comes of “unhonest desire”, neglecting the authority of parents, and getting your advice from drunken gossips and superstitious friars (“the naturally fit instruments of unchastity”). (Perhaps Brooke was harsh toward superstitious friars. Nevertheless, I give him credit for hating Friar Lawrence.)

We are all interpreters of stories, the storytellers as much as the rest of us. The special power of creators is in deciding what will be interpreted, not how it should be. Readers sometimes work out a story to its implications farther and more clearly than the author himself. A story stands as it was created. It is not, in the end, what the author meant but what he said, and that anyone can know.

That requires, however, reading the book. It’s only fair.

Even Shakespeare knew that Romeo and Juliet was not a romance though — it was a tragedy (it’s in the name). The entire story is about people making stupid decisions (adults waging a foolish war, children ignoring it in favor of short-lived peace, near-sighted solutions to larger problems, etc.) It’s only been in the last hundred and fifty years or so that people have largely seen R&J as a romantic drama, and not the tragedy of errors that it was written as — Rosaline was included as a deliberate foil for Romeo’s affections, making the entire thing more tragic because the audience knows from the start that Romeo is a bit of a flake and that (if given the right distraction) the entire mess with Juliet and thus the deaths of both could have been avoided. Every main character in a classically-written tragedy has their fatal flaw, and Romeo’s is that his infatuations run too strongly and rule him rather than the other way around.

To get all postmodern, it could be that Romeo’s declarations of undying love were true until they weren’t. Perhaps his love for Rosalind could have been undying if he had never met Juliet.

Or while he may say what he means, what he means isn’t terribly precious.

We’re made in God’s image, and God is the ultimate Author, who determines not just the content of reality but also the meaning of everything. It doesn’t matter what I say about something; if it goes against what God says about it, I’m wrong. Period. Granted, there may be some gray areas when you step onto the lower plane of human existence (the image is not the exact essence; and how exactly does free will play out in all this?) but we still need to be careful not to fall into Stan Fish’s rather slippery method of interpretation.

There’s nothing wrong with expressing different viewpoints (I actually semi-defended reader response theory in a paper once, which my Bible college prof approved…mainly, that fanfiction is a form of RRT, and it’s okay to play and have some fun with it, as long as we don’t call it canon). It’s a matter of stating an opinion vs. being dogmatic. Fortunately, at least in the Bible, “The main things are the plain things, and the plain things are the main things” (Alistair Begg).

I’m not saying you’re being dogmatic or calling anything canon. Just felt the above needed to be stated for clarity, which you may agree with but isn’t readily apparent in your article.

I guess it makes sense that Bible college profs aren’t supposed to approve of reader response, but that just kinda baffles me all the same. Authoritarians, man.