The Answer To The Ultimate Question Of Life, Fiction Universes, and Everything

If I do it right, this column will address three topics — the meaning of “Christian” from last week’s discussion, why we can enjoy “unsafe” stories, and why stories need good theology as argued here — all in one column. And all for the sake of making us all happier.

Which, to spoil the ending, is exactly the answer for why I should want to do anything.

1. The Ultimate Answer of (Christian) Life

Yes, I’m “hitchhiking” for the title, yet also for this famous argument.

Lost in last week’s comment discussion, and particularly my defense of defining the term “Christian,” was this truth often unspoken, which must be spoken far more often:

I believe things like “the word Christian has certain meanings and non-meanings” and “God fully reveals Himself in His Word and in Christ out of love” not because I simply believe it’s obeying God (though it does obey Him), or to be clever, or to win friends.

I don’t even do this just because I believe it’s my God-given duty (yet this is also true).

Rather, I should want to do this solely because only in so doing can I approach everlasting, pure, unadulterated, blazing, color-shining, full-orbed, eternal, God-glorifying happiness.

2. The Ultimate Answer of Fiction Universes

Last week’s column also ended without a conclusion. I suppose I enjoyed it more that way.

Its unspoken question was: having confirmed that no genre of story is “safe” for Christian fans, why should we have anything do with stories in the first place?

You may be a hemline-measuring cultural fundamentalist or a grity-and-violence-loving art critic. Either way, you would likely answer according to one of these four reasons:

- Entertainment. “It’s just a story.” (My response: then why do we care to defend it?)

- Edification. “Stories show Good Moral Examples.” (Then read the Bible or a biography.)

- Education. “This helps me learn about X.” (Try a textbook; it offers far less confusion.)

- Evangelism. “By supporting this — select one: A) gritty and ‘realistic’ B) sentimental and ‘wholesome’ — story, I reach out to my non-Christian neighbors who otherwise think that Christianity is — select one: A) too sentimental and ‘wholesome’ B) too gritty and ‘realistic.’ (But fiction is useless and boring if only in service to Evangelism.)

Just like a Christian’s work for God is never less than a duty, but is more than that, my reasons for reading, enjoying, defending, and trying to write fiction are based in this:

Story’s chief end is to help me glorify God and enjoy Him forever.

In other words: I’m chasing eternal happiness in God. Stories help me do that. Therefore, stories have meaning — meanings that include all four of those E-words, but are far greater.

In other words: I’m chasing eternal happiness in God. Stories help me do that. Therefore, stories have meaning — meanings that include all four of those E-words, but are far greater.

I needn’t feel forced to enjoy or promote a story because it will be Wholesome or Gritty and impress the pagan neighbors who have whatever preconceptions about Christianity.

I also needn’t feel guilty if I read a story that other Christians wrongly condemn as “unsafe” or cannot themselves honestly enjoy. As long as I’m truly worshiping Christ (even subtly) in this enjoyment and not being personally tempted to sin, I’m free. It is a perfect freedom.

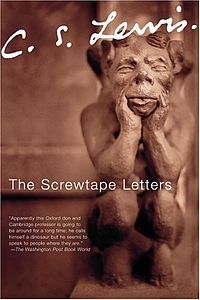

Without this view of freedom, I believe we’ll end up back in slavery. We’ll drift toward other, lesser reasons for excusing stories — reasons closely related to that worldliness or legalism that you thought you left far behind. We may become like the human patient in The Screwtape Letters whose demons tempt him not to read books for the simple pleasure of enjoying them, but for Hellishly “pragmatic” ends. Screwtape devilishly instructs:

Without this view of freedom, I believe we’ll end up back in slavery. We’ll drift toward other, lesser reasons for excusing stories — reasons closely related to that worldliness or legalism that you thought you left far behind. We may become like the human patient in The Screwtape Letters whose demons tempt him not to read books for the simple pleasure of enjoying them, but for Hellishly “pragmatic” ends. Screwtape devilishly instructs:

The man who truly and disinterestedly enjoys any one thing in the world, for its own sake, and without caring twopence what other people say about it, is by that very fact fore-armed against some of our subtlest modes of attack. You should always try to make the patient abandon the people or food or books he really likes in favour of the “best” people, the “right” food, the “important” books.

I don’t want to become that person. So I chase after “disinterested” enjoyment — which is really another way to say that I want to enjoy things the way I would if sin never existed.

3. The Ultimate Answer of Everything

Great stories not only become greater with theology, they require theology because of the definition of “theology.” Theology = God-ology. The study and knowledge of God, which always, always leads to head-over-heels adoration of God. To know Him is to love Him. To love Him is to know true pleasure and joy. To know true pleasure and joy is to be happy, truly happy, no matter what suffering or criticism or made-up moral rules may come.

The greatest stories make people happier. God makes people the happiest.

Therefore the truly greatest stories show us more of God.

Anything less can only bring self-hating, enslaved, joyless living.

A while ago, I was in an art museum and derping around the modern art section where I found an inexplicable blue square wooden pillar, about six feet tall, with a thin white painted line around the top. The piece was called “The Sea” and the plaque said it was supposed to be experiential art. I can kinda-sorta get what was meant because the sea is a literary symbol of the unconscious and the art piece was supposed to be about your individual reaction to it as you walked around it. However, my experience was one of bafflement, anticlimax, and general WTFery. It was a blue wood box.

That is pretty much how I feel about this rambly path of articles that leads to the conclusion of “like what you want to like.” I was gonna do that anyway, but thanks, I guess.

But kudos for this site trying something a little different, something more in the more subjective line with plenty of opinions bouncing off each other. And I would like to thank RL Copple in particular for giving me even a vaguely defensible opportunity to use moderate swearwords. I took much delight in that, juvenile as it was.

Thanks!

Just don’t miss that key clause happy in Jesus Christ and its derivatives. 🙂

Apart from Him, as He has revealed Himself and His will in His Word, true happiness does not, cannot exist. Such a notion itself is a blatant impossibility. One cannot be any kind of actual “hedonist” without the all-vital modifier in front: Christian.

I think this article say quite eloquently everything I’ve wanted to say about Christian fiction. Contrary to popular belief, Christian fiction is not “in trouble.” It is different than “secular” fiction or whatever that means. It has to be. Because we’re called to be different than everyone else in the world. And that’s what this article lays out nice and bluntly.

Well done!

I’ve always tentatively agreed with you on the whole holy joy thing — it’s a Lewisian idea, probably also a Biblical idea, after all. But my reason for loving storytelling is slightly different.

Life is small and disappointing. There must be greater truth and meaning than what we experience. So, we need stories to put our lives in the context of what really matters. For me, this is the most important reason to love great stories, because I’m dissatisfied with life and with my experience of Christianity. I’ll admit, though, that this line of reasoning has occasionally lead me to think that Tolkien (or insert-other-great-author-here) is a better worldbuilder than God. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that this world would be as glorious and meaningful and inclusive as all our most beloved stories and myths are, if only this world were not fallen.

One of my reasons for preferring speculative fiction to general or realistic fiction is similar to bainespal’s comment above– it reminds us that even though we feel like crawling hashmarks on a gritty chalkboard, there is more to life than we normally see.