Speculative Fiction Writer’s Guide to War, Part 6: Psychology of Warfare: The Act of Killing

Travis C. here, filling in a bit for Travis P. We both contributed to this article, and you probably remember we’re both warfighters of the U.S. military. This is a sobering topic, but it’s also part of our mission (at least being prepared for such times as we may need to). We’re also writers and this discussion is in the context of writing speculative fiction, especially fantasy and science fiction. There’s no short shrift here, only humility and honesty. As the Micah prophesied, we’ll eventually turn swords to plowshares and spears to pruning hooks.

According to Dave Grossman’s book On Killing, the biggest stressor human beings face in combat is killing other human beings. The sequel to On Killing, On Combat, actually puts more emphasis on the danger of being killed, but both things haunt the human mind, largely based on the human ability to feel empathy. Feeling the suffering of the humans we kill on the one hand–and to witness friends and colleagues being killed on the other, empathetically feeling their pain as they pass on, worrying that we might be next. These particular fears are the primary causes of battlefield psychological trauma according to On Killing and On Combat. Natural human empathy does not like to be at war against other human beings.

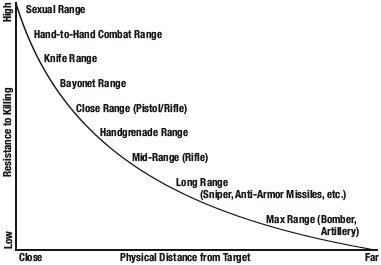

Grossman outlined several significant factors that influence the human response to killing another human being: the influence of authority, the influence of a group’s support for the warrior and perceived legitimacy of the act, the training, conditioning, experiences, and temperament of the warrior. But two key conclusions of Grossman’s research are that killing another human being is hardest when it’s face-to-face and when it involves stabbing into another person’s body. The first part of this involves the fact we humans read one another’s emotions primarily through facial cues. For almost all people, witnessing another human suffer causes at least a weak empathetic response. Like laughter or coughing becoming contagious, the normal human psyche feels a reflection of another human being’s suffering.

It’s about distance

If people are too far away for their faces to be seen, as in a combatant firing artillery or dropping bombs, killing bears a lesser psychological effect–unless the recipients of bombing or shelling are seen up close later. Hard, close combat causes psychological injury to human beings–submarine crews or bomber squadrons in WWII, who were in fact in as much or more danger as infantrymen, were usually less traumatized by their experiences. (Note that while snipers fire from far off, their use of optics brings their targets pretty close visually.)

Note also how this factor relates to the “chase” instinct mentioned in last week’s post. When an enemy turns and runs away, it is easier to kill them by stabbing them in the back than it is to stab them while facing them. Let’s compare that to an old cultural prohibition from the Wild West: only a coward would shoot a man in the back. It might be considered more honorable to shoot someone while facing them and wrestling with the emotional consequences of one’s’ actions. It is also significantly safer to shoot someone who can’t see you, making it more likely someone might choose to pull the trigger who otherwise would have chickened out. Our ancestors judged this act to be villainous and our sense of righteousness in combat tends to recoil in response.

It’s about method

It’s about method

The “stabbing into another body” concept from above is perhaps a particular issue because it seems to strike people instinctively as being interlinked with sexual intimacy and therefore especially wrong (and for certain criminally disturbed minds, especially exciting). It happens to be true that stabbing into the body is a very effective way to kill people, generally superior to slashing or smashing. Yet human beings have often gravitated towards weapons that swing in order to slice or crush as a means of killing instead. It’s worth considering that one of the reasons why a person might use a sword to slash or hack instead of stab has nothing to do with weapon effectiveness, but rather with a psychological factor of avoiding putting a penetrative wound in another person, up close and personal.

Related to the revulsion against stabbing into other human beings is the terror that the thought of having someone else do that to us inspires. Humans are certainly afraid of being bombed or shelled, largely because the terrible noises the explosions make, but we’ll take our lives into our hands in automobiles in reckless ways without much fear at all. It’s different when someone is deliberately trying to kill you. And while the idea that another human would drop a bomb on you or target you with a sniper rifle certainly can inspire fear, most people are more afraid of an enemy who will stab them to death with a knife up close.

Popular media and killing in war

Fantasy and science fiction have described a range of emotional responses to the act of killing, and I would say that many in the military have been influenced by books, movies, TV, and comics as they consider the choice to join the armed forces. You, dear author, have a powerful tool in your hand as an influencer of future generations.

I have one specific example I want to end on, but to begin, let’s spitball a bunch of popular examples of killing with a note on realism:

Example 1: In Star Wars, we see several leaders within the Empire react to the power of the Death Star. They see it only as a tool to bend others to their will, and never react to the decimation it causes when leveled against a planet.

Example 1: In Star Wars, we see several leaders within the Empire react to the power of the Death Star. They see it only as a tool to bend others to their will, and never react to the decimation it causes when leveled against a planet.

Conclusion: Extremely unlikely, even so far removed from the target. You just destroyed a planet for goodness sake! Not even a tear?

Example 2: The helmeted-lackey who pulls down the priming lever for the Death Star’s weapon: no visible reaction (at least, Lucas never shows us that part of the story).

Conclusion: Not as unlikely, but still a little extreme. That soldier is acting under very powerful authority, likely highly trained to follow rote procedure, and is highly distant from the consequences of his/her action. (No one is looking at the planet, right?)

Example 3: It’s October, so the endless reruns of our most popular horror series should be on everyone’s radar. There’s a reason such franchises maintain their popularity: we’re all scared of being stabbed in the dark, alone, by a tall, scary being like Michael Myers.

Conclusion: While the concepts are usually over-the-top, the horror genre as a whole has done well at capitalizing on a core fear of ours, and our reaction to those characters (abomination) is reflective of that.

Example 4: The frequent use of phasers in the Star Trek universe.

Conclusion: It’s one thing to lay down cover fire, another to actively target and kill those enemies standing before you. We rarely see evidence of Kirk and his companions (forward through the rest of the franchise) wrestling with their emotions. There are some examples of the impact distance has (is firing a phaser at a being the same as launching photon torpedoes against a vessel, or bombarding a planet?) We do, however, see the disparity between races/species and how training makes a significant impact on certain groups. For example, take your average Federation human, Klingon, and Vulcan and you can discern differences in reactions and responses based on historical, cultural, and species-level differences.

I’m picking some low-hanging fruit, but look at your favorite series and you should find examples that either support the analysis Travis P gave, or seem over-the-top in comparison and therefore should strike us as awkward. It may be entertaining, but it isn’t an accurate portrayal of reality. In reality, killing is hard and it impacts the warfighter.

Finally, an example that gets it well, and one that gets close but not quite.

Many readers may be familiar with Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive. It follows a small cast of characters as they navigate a world on the brink of destruction from ancient powers, all while humanity is fighting amongst itself for power and supremacy. Enter Dalinar Kholin, brother of the king, Brightlord, and Highprince of War of the Alethi armies. He has received visions and knowledge of an ancient path known as The Way of Kings, a code of honor that he attempts to resurrect among the factious Alethi. His son, Adolin, doesn’t quite get it, but is strongly influenced by his father. This part of the plot is in stark contrast to Brightlord Sadeas, who basically represents everything we would ever hate about a person (selfish, backstabbing, conniving, spiteful, basically awful in every way).

Many readers may be familiar with Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive. It follows a small cast of characters as they navigate a world on the brink of destruction from ancient powers, all while humanity is fighting amongst itself for power and supremacy. Enter Dalinar Kholin, brother of the king, Brightlord, and Highprince of War of the Alethi armies. He has received visions and knowledge of an ancient path known as The Way of Kings, a code of honor that he attempts to resurrect among the factious Alethi. His son, Adolin, doesn’t quite get it, but is strongly influenced by his father. This part of the plot is in stark contrast to Brightlord Sadeas, who basically represents everything we would ever hate about a person (selfish, backstabbing, conniving, spiteful, basically awful in every way).

Spoiler alert……

When Adolin reacts to Sadeas at the conclusion of Words of Radiance, we all rejoice a little bit. Comeuppence is given. A wrong is righted. But Adolin immediately knows he’s in the wrong. He took the coward’s way. He reacted to the right circumstances, took the action he deemed necessary, but he killed a man kind of out-of-combat by stabbing him face-to-face in the eye. For one who gained notoriety through dueling, whose father is trying to bring about a seachange in the belief system of the entire army, Adolin knows this will be devastating. What a great place to begin the next book, Oathbringer, and watch him wrestle with the consequences of his actions, of his moral and ethical dilemma, and his reactions to those around him.

Contrast that with a childhood favorite of many. Let’s see if you can guess where I’m going.

“I will go up to the six-fingered man and say, ‘Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

“I will go up to the six-fingered man and say, ‘Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

Since he was eleven years old, Inigo has been preparing himself to do one deed: avenge his father, a master bladesmith who crafted a master blade, was refused payment, and was murdered by the six-fingered man. It’s hard not to feel satisfaction when his duel at the end of The Princess Bride comes to its inevitable conclusion. And let’s face it, would it be as popular if it ended with, “You killed my father. I forgive you”? Sigh… someday, we’ll have ploughshares.

Let’s take a look at the realism in this example though:

- Authority: Inigo is acting on moral authority to right the wrong of his father’s death and stop a murderer (take that in contrast to two combatants fighting one another in war… )

- Experience: Certainly the death of his father has galvanized Inigo into the hardened fighter he is today. It spurs him on against all odds. He has intentionally chosen to never forget what occurred and to actively pursue the training and opportunity to get revenge.

- Training: A lifetime of training has molded Inigo into a consummate swordsman (bested only by the Dread Pirate Roberts, right?) It’s probably accurate to say that he has trained out any emotional reaction to killing the six-fingered man. In his mind, Inigo isn’t taking a man’s life, he is stopping an evil.

All of that should support the idea of Inigo as an elite warrior (which we’ll get to next week) incapable of fear.. Which leaves me struggling with the likelihood that the six-fingered man just happened to kill the father of an eleven-year-old boy who happens to be in an extremely small category of people who can conduct an extremely intimate act of violence (stabbing, face-to-face, while in close proximity) and have no reaction afterwards. He just runs to Wesley’s aid and they escape like nothing’s happened. He solemnly nods his head, “Yes, the six fingered man is dead.” WHAT!!! YOU STABBED A DUDE!!! THAT’S CALLED MURDER!!! (Author Travis’s reaction.)

Admittedly, The Princess Bride leaves us behind before the victors can stop and really process their emotions. We don’t see Inigo struggle to overcome the consequences of achieving his revenge (Now what? Take up Sudoku?) We don’t see him wrestle with the question of whether he truly achieved an honorable outcome for his father’s memory. We don’t see him have trouble reintegrating into society as the unforgiving guy who stabs people and doesn’t ever let go of a grudge. Or the guy who pursues justice at whatever cost to himself.

As authors, we have the ability to help our audience wrestle with those realities. We can provide a glimpse of how our hero, or villains, actions may or may not impact them and open that up for discussion. Next week we’ll introduce one such example, the idea of the warrior elite, a very small percentage of humans that are capable of violent acts with seemingly no emotional impact. Till then, let’s close with a quote from On Killing to help you frame the challenge of killing others in your stories:

The basic aim of a nation at war is establishing an image of the enemy in order to distinguish as sharply as possible the act of killing from the act of murder.

— Glenn Gray, The Warriors

I wanted to personally thank you for this series – I have a character that has been through war and is trying to live on the other side -this insight into the soldier and warfare has been exceedingly helpful. I have been following them with great interest.

It’s absolutely our pleasure Lorraine. I remember a world-building resource called Eight Day Genesis that felt similar. It read like a series of articles (with different authors too, so very different voices). It wasn’t a recipe, but it at least reminded you of all the ingredients available and many you hadn’t thought of before. I hope we can do something similar. While reading all of the books available on warfare would be great, maybe we can give you enough to get started and make the story just that little bit better!

See also: quite a bit of post-WWI literature. Hemingway in particular. The style of warfare had shifted enough to the long-distance, modern approach that it was doing that new sort of psychological on the soldiers, that you could be killed by people you never saw and never saw you. (And the realization that you were doing the same to the other side.)

There is also a lot of work put into dehumanizing the enemy, whether by means of propaganda or less formal means like (raaaaaacist) nicknames like the jerries or the nips or what have you. It doesn’t always work to override natural empathy, but it’s probably more disturbing when it DOES.

Whether or not people have built empathy in the first place might be part of this as well. We hate the idea of killing because we live in a relatively decent society where fellow humans are often friends, family, or significant others. Someone that, as a child, wasn’t raised to have a close bond with others(had little to no affection from a caregiver, or, especially, lived with abuse and never had a context outside that) might not be bothered by killing as much, at least until they do have a chance to have a close bond with others(depending on their personality type. Some people develop things like NPD and become horrible people.)

People also are happy to kill people they see as inferior or evil. Nazis were happy to kill Jews, and many modern people talk as if they’d be happy to kill Nazis.

Gonna also talk about Fate Zero and Naruto/Naruto Shippuden again since there’s so many interesting examples of death/killing in there, too. There’s characters like Kiritsugu and Itachi who put aside their feelings and kill because they see it as necessary in the moment. Sasuke, Itachi’s little brother, is also an interesting example, since he’s sought revenge his whole life and there was a bit of a consequence to achieving it.

Kiritsugu is a very sad and tragic case, because early in his childhood he had an example where he hesitated to kill when it was necessary, and a large swath of people died as a result. So he’s a lot more willing to kill from then on, and becomes somewhat numb to it even if he hates it. His situation is a bit different than the average soldier because the first few time he had to kill, it was someone he cared about, but throughout his backstory he is still shown killing strangers and witnessing deaths of people he doesn’t know well, and from the way he ponders it, it obviously has an effect on him.

The thing in Star Wars you mentioned never really struck me as odd, considering how ruthless the Empire was supposed to be. They kind of seem like Nazis in the the way they indoctrinate their soldiers, and they would probably only put people in command if they seemed suitably brainwashed to Empire ideals. None of the other workers on the Deathstar would be able to show compassion for those they kill in the name of the Empire because that might cause them to get punished or killed. So any reaction they had would have to be on the inside. Novels written in the Star Wars universe tend to show more of that.

Travis C, thanks for adapting the material we started working on a couple of weeks ago for this week’s post. I appreciate it.

No worries at all partner. I’m just happy to be along for the ride with someone so skilled and experienced.

Wanted to share another example that came up for me this weekend. I’m a sucker for westerns, and really enjoyed the latest retelling of The Magnificent Seven. I think Antoine Fuqua did a great job, as discussed in the special features, of painting a diverse picture of the Seven and their motivations & experiences. I found Goodnight Beauregard a well-thought out character, as he’s shown to struggle with the misalignment of his reputation (skilled sharpshooter) and reality (not a killer). Antoine doesn’t delve into it, but I was left wondering if he ever really pulled the trigger as a Reb. It also raised the question of cultural differences, as the Comanche, mercenaries, homesteaders, warrant officer, hermit, and others collide.