Speculative Fiction Writers Guide to War, part 16: The Costs of War

Travis P here. Since our last post of our Guide to War covered Combat Support Training, it seemed natural to segue into another type of support for combat–those things a nation needs to do in order to support and field an army. That is, the costs of war, as Travis Chapman is about to explain in general terms (future posts will provide some guidance on how to compute war costs):

Travis C here with a continuation of our post series The Speculative Writers’ Guide to War. As Travis P and I discussed where we wanted to head next, we knew that we needed to address the cost of war. We’ve discussed why a nation (or other entity) might chose to go to war, where their military forces might come from and how cultural and social factors might influence how they experience combat and how they might train for it. Lingering in the background is cost. War costs us something. We’ll spend some time dissecting how those nations will consider the cost of war before we move on to how planning and operations work.

We could go to several sources to frame a dialogue on the costs of war. I propose the Bible. Not surprising at all, Jesus gave an expert analysis of the cost of war. His statement in and of itself is worth our analysis:

“The Return of the Ten Thousand,” Public Domain image by Herman Vogel

“For which of you, desiring to build a tower, does not first sit down and count the cost, whether he has enough to complete it? Otherwise, when he has laid a foundation and is not able to finish, all who see it begin to mock him, saying, ‘This man began to build and was not able to finish.’ Or what king, going out to encounter another king in war, will not sit don first and deliberate whether he is able with ten thousand to meet him who comes against him with twenty thousand? And if not, while the other is yet a great way off, he sends a delegation and asks for terms of peace.” Luke 14:28-32 ESV

Travis P used this verse earlier in our series, but I think it’s worth returning to. In no particular order, a few things stand out to me looking through this lens of “costs of war”:

- Offensive (going out) and defensive (build a tower) actions may require different analysis

- The time to count costs is while sitting down, not after the foundation is laid

- When it comes to towers, a finished product matters

- Better to make terms before the war begins

- Numbers mean things

- Costs may be material, human capital, and even pride

Those last two strike me as a author. It’s not that ten thousand can’t defeat twenty; we’ll spend some time discussing force ratios in future posts. It’s that disparities like that should strike us as odd, and the emotions of those involved should reflect that. Our king who sends the smaller force, and the soldiers in that force, should recognize the dire circumstances leading to the decision to march, or the ace in the hole they are relying on to overcome the numerical deficiency, or the ineptitude or lack of foresight on the part of commanders to order forces into such a situation without knowing the enemy strength ahead of time. The leaders of the superior numbers should display confidence, even bravado, or maybe disdain for the smaller forces.

That’s when you can turn things on their head.

Or let things play out as expected.

The other point of note is in the types of costs that Jesus identifies:

Material costs

It’s no surprise that going to war costs money. As authors, we get to decide what exactly that means. Many of the material costs of war can be categorized as sunk costs (made one time, but never again thereafter), recurring costs (on some periodicity), and emergent costs. A nation may pay for those out of existing materials, purchase them from the coffers, capture them, or take them by other means. Consider the following examples:

Sunk costs

- The king re-purposes a frontier lodge into a watch tower, rather than pay for new construction (existing stock)

- The king raises taxes and drains the treasury to fund construction of a new wall

- The warlord captures key castles along a river to build a defense network

Recurring costs

- The king’s soldiers require food and spare leather for a campaign. Every village is required to provide a levy of grain each month and a grown cow per year.

- The king purchases weapons from a guild of craftsmen through taxes

- Soldiers forage for food and glean off the fields of conquered lands

Emergent costs

- After losing many battles and being driven to the sea, a lord must bargain for passage on merchant ships to return home

- After losing many battles and being driven to the sea, a lord lays claim to a merchant fleet and takes the ships by force, treachery, or charming good looks

- The imperiled lord, frustrated by his attempts to get ships and desperate,… you get the idea.

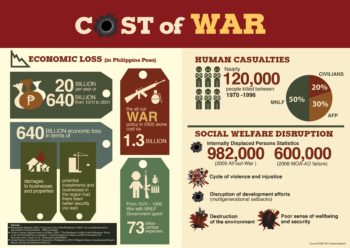

This chart analyzes the cost of a specific war: The civil war in the Philippines between the government and MNLF rebels

You certainly don’t need to micromanage every grain of corn, every silver buckle, each force grenade holster in black leather, and the annual fuel supply for your hyperlight drives. That may be interesting and help with your worldbuilding and plot. It might be a way to introduce tension or uncertainty into the plot (our supply of hyperlight drive fuel was waylaid, now we’re stuck on this planet). At least a tacit acknowledgement that everything came from somewhere, at sometime, even if miraculously, will keep the realism going.

Human costs

If you are writing about war, then you probably have an existing point of view on the human costs. We’ve discussed some of the psychological and physiological impacts on a soldier in combat, but this lens looks at things little differently. Generally, we expect people, soldiers and/or civilians, to die in war. That covers a wide spectrum: non-combatants, participating combatants, combatants drawn into the fight but not aligned either way, innocents, collateral damage, etc. The following thoughts may stir up other possible human costs of war:

- Those maimed in war but not killed

- Those disenchanted and disenfranchised, who change sides or work against their initial cause

- Family relationships wrecked by war: divorce, separation, emotional distancing, trouble reintegrating

- Lost future opportunities. Since the soldier is off doing “war,”they aren’t pursuing something else, like art or commerce

There’s many more, and each of the ones given here could be expanded into thousands of possibilities. Some of those possibilities might actually be positive ones (ex. I’m glad Boramir went off to war because he was a jerk and we didn’t like him around here anyways). Many will be viewed as negative of course. Whether acknowledged or not, there is always a cost.

Pride or Belief in a Cause

I’ve added this one in from my interpretation of sending delegations for peace terms. A wise ruler would recognize when to fold and find a non-combat solution that saves his or her people. We’d identify a ruler who fights in spite of that recognition as pursuing war out of pride, spite, or hubris. A familiar trope is showing us the haughty ruler pursuing victory through combat at the expense of soldiers, as if from the soldier’s vantage the war is purely for vanity and no material purpose.

Credit: Crop of original artwork by Darrell K. Sweet for A Statistical Analysis of Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time

Of course, some causes are worth fighting for, no matter what the human or material costs. Existential evil tropes rely on this belief. Sauron must be defeated. Thanos must be stopped. The seals holding back Shai’tan must never be broken. Of course, each of these adversaries have their own justification for bringing war upon their world, which must be considered. In the Wheel of Time series we see many nations ally together when past experiences of war among each other must be overcome for a greater good. Those rulers must submit themselves at the cost of their pride to a greater authority.

My fellow Travis, thanks for supplying the content for this week’s post. I appreciate your hard work!

No worries at all! This week is was shoveling snow, solving neutron transport equations, the Brayton thermodynamic cycle, and more snow. So costs of war was a welcome relief!

The new Voltron series kind of has an interesting take on the supplies for war thing. We have the Galra Empire enslaving planets and stuff to obtain quintessence and crystals. What’s also interesting is that they seem to need those things in order for their society to run as they’re used to, which is part of why they go to war in the first place.

Something I’ve noticed with the cost of war seems to be the difficulty of balancing the welfare of fighters, etc. with the mission the war is trying to accomplish. In my current WIP, this becomes a dilemma for the leader of the faction the main char joins. The faction leader knows the main char joined because he planned on using the misery of war to force himself to be grateful for the peaceful life he has with his family.

That intention was revealed to the faction leader when she first interviewed the main char for a position in her faction, but she immediately criticized his motives. She lets him join, but says his reasons are ridiculous, considering the high death rate of war. She lets him join because he could be useful to her faction, but she bluntly says that she hopes he’ll resolve his personal issues quickly and return home before he dies.

But then eventually she realizes that he probably won’t ever decide to return home on his own, for various reasons. So then she has to choose between furthering the welfare of her faction(which means keeping as many decent fighters as possible) or what she sees as the welfare of the main char and his family(forcing him to return to his family).

I guess in real life one such dilemma could be in terms of where someone is stationed? I dunno. One youtuber I listen to was saying that one reason she married her boyfriend quickly was partly to increase the likelihood of her being stationed in Japan where she could actually see him and spend time with him. I can try to find the video and link it if you like. But, yeah, weighing out cost/effect/impact seems to be one of the most interesting but also the saddest part about war.

Thanks Autumn! I’m trying to recall where else I’ve seen it, but the trope of “Well, things have always been this way and we’ll do anything to keep it so” has always interested me. How far will someone go to maintain the status quo? I feel it’s easy to imagine getting stuck in a pattern and numb to ones actions after a period of time. I guess kind of Jupiter Ascending-ish.

I hadn’t thought of it in those terms before, but my wife and I had an early life experience similar to your example. As a submariner I was on patrol for months at a time, then in homeport for a month or three, then back out again. We dated through a patrol, were engaged together through a patrol, but actually had two weddings in the off-time before my next patrol. She finished an internship at Campus Crusade (Cru) and moved to Florida earlier than we planned so we could get married in time to start healthcare and other benefits ahead of my next deployment. Just our pastor and two witnesses for #1, then later on we had a full ceremony #2 with family & friends. And a much delayed honeymoon. Had we waited, it would have been even harder for our next assignment overseas to have worked. We laugh about it now, but it was a huge decision for us when all that uncertainty was in the air. Not surprisingly, many military relationship events occur in the periods surrounding deployments (Oh, I’m deploying? We better get hitched then)

Hm…now that I think about it, I think dealing with deserters could be another place where the welfare of the troops vs. the mission and ‘this is how we’ve always done things’ tropes could manifest. I remember watching part of the newer Lonesome Dove series with my Dad, and there was something with deserters there. The main char was having a bit of a dilemma since he was hired by the military as a tracker, but part of his job was tracking down deserters so they could be brought back and executed. The main char was interacting with another member of the army for a lot of that episode, and that member was determined to execute deserters almost no matter what. Even maybe after he he came back to camp and saw his regiment or whatever destroyed by the enemy.

When I first went to college I heard someone telling the story of their grandparents or something, and in that particular case, the grandparents got married, thinking that the guy wouldn’t get deployed soon. But he did get deployed and died before he could return home, though I’m pretty sure they were glad they got married regardless of what happened.

Marriages around the time of someone’s deployment seem like a good way to add romance and maybe tragedy, though the trick might be figuring out how to approach it without being too cliche.

The whole thing does sound romantic in a way(lol, part of me cringes at saying something so blatantly sentimental). But then maybe it could also be fuel for rushed decisions(which are a bit of an anathema for people like me).

Good lord. Longest running series ever.

True. And not ready to finish yet.

What can I say? Some subjects take more time than others. And number of people have expressed interest in the book that will eventually be put together from all these posts.