Speculative Death: Life and Death Among The Immortals

Who doesn’t?

Immortality would be paradise, right? The Bible is chock-full of the joys and wonders that await those who achieve eternal life. No more aging, suffering, illness, or death, though it seems like it’s cheating a little because all that comes after death, and You Only Live Twice, Mr. Bond.

What about eternal life minus the whole death thing? Wouldn’t that be cool? (I’m not getting into the Rapture question here, pre-, mid-, post-, or whatever—that may come up next time, but not today) Can it happen? Hmm. It could have. There’s this odd little passage in Genesis:

And the LORD God said, “The man has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil. He must not be allowed to reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever.” – Gen 3:22

Doesn’t sound very sporting. First, we’re not allowed to possess the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and then, to add insult to injury, immortality is off-limits. Seems like that would fix a lot of our most vexing difficulties with life on Earth. Too bad we can’t rewind history and create a world where immortality isn’t just a pipe dream.

But wait! We can! Speculative fiction to the rescue!

Last week, I talked about some of the different ways our desire to cheat death plays out in spec fic. So, what happens to those fortunate few who manage to outwit, outplay, outlast, or otherwise thumb their noses at the Grim Reaper and gain immortality?

Let’s spend some time among the immortals and find out.

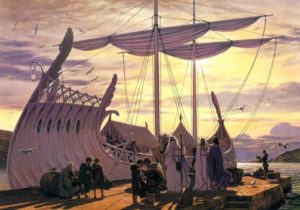

Starting once again with classic literature, some of you helpfully pointed out last week that Tolkien’s Elves were essentially immortal, save from death in war or other violent mishap. They were also subject to a sort of fading away, whether through grief or fatigue of their long lives, and they all eventually set sail from the Grey Havens for a journey into the unknown West, beyond the knowledge of Middle Earth.

Starting once again with classic literature, some of you helpfully pointed out last week that Tolkien’s Elves were essentially immortal, save from death in war or other violent mishap. They were also subject to a sort of fading away, whether through grief or fatigue of their long lives, and they all eventually set sail from the Grey Havens for a journey into the unknown West, beyond the knowledge of Middle Earth.

And as I noted last week, that immortal rake, Dorian Gray, despaired of his debauched existence and ended up destroying the portrait that sustained his youth and vigor, killing himself in the process.

No, I still won’t spoil the end of Tuck Everlasting for you, but I will note that the good-hearted Tucks find their immortality a kind of stasis, in which they remain fixed in time, despite the changes in the world around them.

A similar theme plays out among the immortal vampires of Twilight and Anne Rice’s novels. Life is change and growth. Un-death is a sterile existence without development or progress, where the immortals parasitize the mortals and inexorably lose touch with whatever humanity remains to them.

How are we doing so far? Don’t lose heart…literature is always so grim and pessimistic. Maybe some more modern examples from the world of popular culture, springing from our social enlightenment and advanced scientific knowledge. Yes, that must paint a rosier picture.

In the bizarre 1974 motion picture, Zardoz, Sean Connery portrays a barbarian transported…in a flying stone head…to a land of immortals. Their eternal life has become a torture to them, and their most profound hope is to somehow rediscover death.

In the bizarre 1974 motion picture, Zardoz, Sean Connery portrays a barbarian transported…in a flying stone head…to a land of immortals. Their eternal life has become a torture to them, and their most profound hope is to somehow rediscover death.

Did I mention there’s a flying stone head?

Mr. Connery makes another appearance in the movie Highlander, about a race of immortals locked into a never-ending tournament. Behead your opponent, gain his power and abilities, and live to fight the next challenger until only one remains. The victor wins the ability to guide the course of human history, for better or worse, but eventually, the whole thing starts all over again. On television.

Maybe something higher-brow…Isaac Asimov’s Hugo Award-winning novella, The Bicentennial Man (not to be confused with its pale translation to the big screen starring Robin Williams), concerns a self-aware robot who desires to become human, and after years of modification is indistinguishable from the genuine article, with one glaring difference that prevents society from accepting him: he’s not subject to natural death. Rather than give up his dream, he surrenders his immortality and engineers a way to make his robot body age and die at a human rate. He gains legal recognition as a human being, and then he dies.

This isn’t helping, is it?

Okay, back to the movies. Ron Howard’s Cocoon brings a downhearted collection of senior citizens together with a crew of immortal aliens who are trying to recover some of their comrades marooned on Earth in hibernation vessels. Contact with the alien cocoons rejuvenates the oldsters, but unfortunately drains the life force from one of the aliens inside, killing him. The rescue team doesn’t seem to hold a grudge, and they whisk everybody off to their homeworld, where the seniors will presumably live forever and teach the aliens about the Charleston, needlepoint, and Spam. Wait, wait…there’s a sequel! Some of the immortal geriatrics return in Cocoon: The Return to visit their loved ones and must decide whether to stay on Earth and die, or go back to the alien planet and not die.

Sigh.

In summary, immortality in spec fic is most often boring, futile, dismal, empty, or all of the above.*** It has less in common with life eternal than with death everlasting. Maybe God knew what He was doing when He fenced off that Tree of Life. It appears that making a sinful, messed-up, broken human being immortal would condemn them to an eternity of sinful, messed-up, brokenness. Perhaps immortality is best experienced after death. More about that next week.

***No, I didn’t forget The Doctor, who leads a rather jolly semi-immortality, and there are some other immortal or nearly-immortal characters in his universe that aren’t totally miserable, but I would maintain he’s the exception that proves the rule. Besides, he owns a TARDIS, and that would keep almost anyone amused for several millenia. I now respectfully yield the floor to the Whovians.

Oi! Just because I was thinking of the Doctor throughout the whole article doesn’t mean I wasn’t paying attention so I’m only going to comment… about… Well… fair enough.

*snatches the floor so fast everyone falls over*

First of all, I have to disagree that the Doctor is fine with his near-immortality. Even near the end of the classic series, hints of self-pity begin to creep in:

Well, look at me. I’m old, lacking in vigour, my mind’s in turmoil. I no longer know if I’m coming, have gone, or even been. I’m falling to pieces. I no longer even have any clothes sense… Self-pity is all I have left.

–Six

Think about me when you’re living your life one day after another, all in a neat pattern. Think about the homeless traveller in his old police box, his days like crazy paving.

–Seven

And then in the new series, it becomes full-blown, complicated by his guilt over the Time War:

“I don’t age. I regenerate. But humans decay. You wither and you die. Imagine watching that happen to someone you–…you can spend the rest of your life with me. But I can’t spend the rest of mine with you.”

Ten

Even the time traveling isn’t much of a conselation.

“I look at a star and it’s just a big ball of burning gas, and I know how it began, I know how it ends…and I was probably there both times. You know, after a while, everything is just stuff. That’s the problem. You make all of space and time your backyard what do you have? A backyard. But you can see it. And when you see it, I see it.”

Eleven

And you look at other immortal characters–Jack Harkness, and Ten’s punishment on the Family of Blood is summed up in one line: “We wanted to live forever. So the Doctor made sure we did.” He’s not exactly an exception.

Which episode is the Eleven quote from?

Not technically an episode, it’s from one of the season five bonus clips “Meanwhile in the TARDIS.” Amy asks why he brought her along, and that’s his answer.

Thanks for that clarification, Galadriel. I haven’t watched enough of this series, particularly the recent episodes, to pull out nuances like that. So, it’s not all stardust and jelly babies for the Doctor either. This is why I leave all things Who to the experts. 🙂

I kinda think, especially for Eleven, humor and silliness are coping mechanisms for him. I’ve only seen Nine, Ten, and Eleven, but that’s my understanding. Get him to stop the jokes and games, and he’s a very battered, broken, jaded individual. Eleven is just *really* good at hiding it (at least in season 5….season 6 rips the mask back off). So in a weird way, Eleven’s the most ridiculous of those three, but ultimately only to conceal being by far the darkest.

Agree, 100%. To quote myself from “The Doctor’s Doctrines” post

And what I kept noticing over the course of this season is how helpless the Doctor is, how he is reduced to saying “sorry” so many times, because he can’t do anything else. I thought Ten was the apologizer, but Eleven is having just as much trouble. Even his companions’ faith in him is being twisted–and because he’s my Doctor and Amy’s my first companion, I’m recognizing it along with them. And, Rassilion, it hurts.

He clowns because if he really acknowledged how he feels…I don’t even want to think about what he might do then.

I find it a bit curious because at least two people are recorded as not dying: Enoch (he walked with God, and then he was no more, because God took him) and Elijah (gets taken up into Heaven by a chariot of fire).

I’m a little weird in that I’d choose the ability to heal over immortality. That explanation is one I had explained to me as the reason for Adam & Eve being kicked out of the Garden, and I think it fits. It goes along with God’s marking Cain being an act of mercy at Cain’s pleading rather than judgment. In a broken, corroding world that fades like grass and changes like clothing, immortality would be destructive. Plus, it seemed necessary in the face of redemption somehow, but I haven’t thought that one through yet.

But I also think it’s partly a matter of perspective. Funny enough, some friends and I have between us a series of characters who are essentially immortal (they will not die of natural causes, but they can be killed). One sees it as constantly losing everyone you love. Another sees himself as a kind of guardian & avenger of the innocent. The world’s kinsman-redeemer, in a sense, I suppose, now that I’m thinking about it. Both are true, at least in that storyworld, but the former paints a bleak, eternal death while the other is a new life of itself.

But now we’re back to that “with great power comes great responsibility” bit…

And I kinda think, realistically, even characters who don’t age physically have to continue to be able to learn, develop, and change, because [be happy, Whovians, I’m going to say it] not even an 1100-year-old man knows everything or has exhausted all knowledge & wisdom. In fact, he’s more likely to discover the world was wrong all that time than anything else. Can you imagine thinking the world was only as big as your hometown, only to watch the world grow until we’ve populated it all and jumped into the stars? Can you imagine thinking the empire would never die only to watch it fall and another rise in its place? Imagine watching from a distance Adam to Noah, Noah to Abraham, Abraham to David, David to Christ, and Christ to whenever? Imagine watching technology transform from ancient to the 21stC? I dunno. Immortality might be worth it just to watch the dramas unfold.

Then, I swear, I’m going to live to be 100, then disappear into the woods and become an urban legend. You watch.

Enoch in particular is very cryptic. This is all we know about him. There are several anecdotes in that part of Genesis that leave us waiting for the other shoe to drop, and it never does.

It’s like sitting on the sofa with Grandpa, and he says something like, “Did I ever tell you about your ancestor, Bilious the Pirate?”

“My ancestor? A real pirate? No! Tell me! Tell me!”

“He was the most fearsome buccaneer to ever sail the Spanish Main. Shivers my timbers just thinking about him. Back in eighteen…eighteen twenty sev…zzzzz.”

Hahaha. Yeah, Genesis can be a bit episodic, because it’s a series of “firsts” and such. The other thing I think is interesting is that you have sacrifices to God in Genesis 4, but not until the birth of Seth is it said that “men began to call on the name of the Lord.” By chapter 6 you’ve already got cities, polygamy, arts, textiles, and a million other things. Far cry from the mindless “cave man” depictions.

But that is another rant entirely…

Tiny correction: Asimov’s book is the Positronic Man. They retitled it to the Bicentennial Man for the movie. (And the book is so wonderful and the movie is … Robin Williams.)

One thing I always wondered about was what would have happened had Eve denied the snake. What if Cain or Abel or someone else, hanging out in the garden, got introduced to the forbidden fruit? And the curse descended, not on the entire human race, but on only part of it?

You think our wars have been bad. Imagine being a fallen human and interacting with perfect humanity. We’d hate them with a deathless passion and stop at nothing to exterminate them. Except perfect humanity might very well have powers like teleportation and telepathy, making them very hard to kill. Not to mention they talk to God face to face and we couldn’t do that.

Kessie: Actually, we’re both right. The novella “The Bicentennial Man” came first, winning Hugo and Nebula Awards in 1976. It was later expanded into the novel “The Positronic Man” in collaboration with Robert Silverberg, and the movie came after that.

I read part of an online series once that dealt with this topic, Kessie – it is sort of a blend of Tolkien and Old Testament. The author hasn’t finished it, and I don’t think they update it very often, but here’s the link: http://apricotpie.com/james

Bethany, I read that one too!

Very true. It’s fascinating how even secular SF authors end up circling back to this truth.

I believe, though, that making immortality miserable for nonhuman races is simply authors reading the human condition into all sentient species. We invent these races, and we give them what, at bottom, separates us from the animals – including our corrupt, yet redeemable nature. And it is our sin, as you say, that makes immortality unhappy.

But if God created other races, He created them good. In their natural state they are (like mankind was) sinless. There’s no reason to assume that every other sentient race would fall like ours did. They could fall like the demons did, and be submerged in evil without hope of grace. They could stand like the angels did, and remain in unstained holiness. The immortality of a race like that would be glorious and joyful.

I know: A righteous, immortal, joyful race is a hard thing for a sinful, mortal writer to handle well. But biblically speaking, it’s as supportable as unhappily immortal races.

Thank you for the article, Fred. I enjoyed it.

And C.S. Lewis gives us a hint of that in Perelandra.

Certainly, and something (or more precisely, Someone) is missing from the eternity of those jaded, discontented immortals that makes all the difference.