Shields Among Us

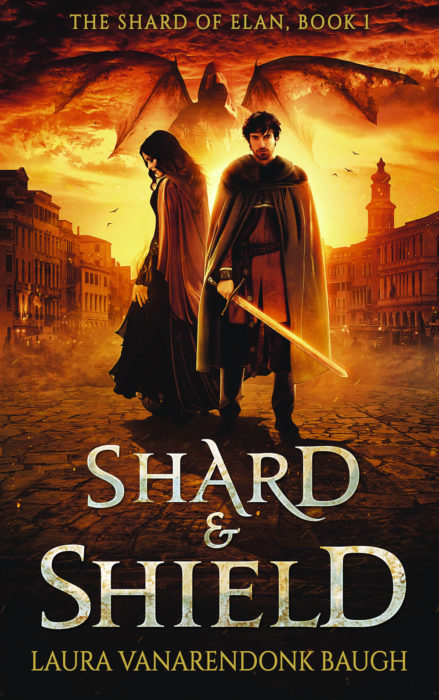

I’ve been working off and on with the story that is now the Shard of Elan series for fifteen years, and it wasn’t until I sat down to write this post that I realized Shard & Shield is misnamed.

In the novel, a natural artifact is needed to power a shielding spell to protect a land ravaged by magical raids. This arcane shield blocks an interdimensional magical race from entering the human world. The shield is key to the humans’ safety. (This is a problem when it’s then broken, but that’s how stories go.)

But this titular shield is far from the only shield in the story. I realized that most of the character interaction (and hence plot) hinges on the many, many shields they have each erected.

Shields are for protection, and that’s generally a good thing. When inhuman magical monsters attack to take the food you need to survive, defending yourself is the right action.

Sometimes shields are a result of trauma. Someone who has experienced abuse or betrayal will be cautious about exposing himself for further abuse. This is a natural defense, but it can also make emotional healing more difficult.

But sometimes we protect what we don’t need to protect, or what shouldn’t be protected, such as social status or a more flattering view of oneself. It can be hard to tell at a glance such a shield’s true purpose or effect—is a barrier to the immoral a protection for the vulnerable moral, or a refusal of redemption?—or even hard to identify shields so common and so assumed that they become invisible, given the same immutable rule as gravity, and thus often even more impenetrable than a visible wall.

Barriers are the opposite of bonds, and in a fractured society with many invisible shields, there are as many fissures to exploit. Someone who cannot work with a group finds it easier to work against that group. Someone who is excluded is an easy target for abuse or exploitation. It becomes more difficult to see the motivations, needs, and fears of others—or to obscure them in the name of defending one’s own needs or wants.

In this way, shields become offensive weapons. They’re like the AT Fields of Evangelion, which are considered purely defensive until they are used to take down satellites and tanks.

Activating a defensive shield inherently blurs one’s perception, here illustrated by Eva-01. (Evangelion)

(Evangelion spoiler: the AT stands for “absolute terror” and is literally a manifestation of the distrust and fear of connection which separates souls. AT Fields are then used for destruction in the name of protecting humanity. Nearly twenty-five years later, it’s still possibly one of the most concise illustrations of today’s politics.)

It’s been said there aren’t traditional villains in Shard & Shield, despite it being an epic fantasy. The war is terrible, but the reader is sympathetic to both sides. People do terrible things, but they are often motivated by what seems to them good reason. I would say there are definitely villains! but they are not necessarily characters. The evils in the story are not people, but the concepts people choose and then wield against one another, creating conflict which spreads and generates greater conflict. Even the most-hated character is acting in self-defense, with awful effects on those around him.

I feel this is a more realistic depiction of conflict. Not that evil doesn’t exist; it certainly does, and we can observe that. But as Good Omens (Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett) succinctly and snarkily puts it:

“…most of the great triumphs and tragedies of history are caused, not by people being fundamentally good or fundamentally bad, but by people being fundamentally people.”

Evil doesn’t have to work as hard when we already prefer to fracture ourselves with distrust or resource-guarding, making fear-aggression and neighbor-exclusion our default behaviors.

And when a situation truly is evil, our exclusionary barriers and defenses may actually make it easier for that evil to gain a foothold. As playwright Steven Dietz noted in the classic tale of an incarnate evil, Dracula:

Most of the characters in Bram Stoker’s Dracula spend the better part of the book trying desperately—with the absolute best of intentions—to keep secrets from one another. Their reasons have to do with safety, honor, respectability, and science. But every secret buys the vampire more time. Every evasion increases the impossibility of anyone assembling the totality of the facts, the cumulative force of the information. Secrecy breeds invasion. Darkness begets darkness.

In Shard & Shield, every advancement, every achievement happens when a character is bold enough to break through an established barrier, to push past a social or personal hurdle to do something that should not, by traditional wisdom, have been done. Of course, pushing past barriers and inhibitions can also trigger awful events, because sometimes those barriers and inhibitions are shields to protect from real consequences. Discernment is important. But without the willingness to try, and to take risks in opening to others, nothing good would happen, either.

Whew—even as an author I’d never thought of my story this way, much less written it all out like this, and I hope it does not sound ridiculously pretentious now! But I believe fantasy allows us to explore reality more realistically, if you will, by letting us view real issues from a different and safely distant angle. Thinking about the shields we all carry, and which are necessary and which are harmful, might help us in real life, both when we are called to answer the question of, “Who is my neighbor?” or when we are tempted to shield against help or friendship or other good things in the name of defense.

Shard & Shield is available now. Lorehaven magazine says:

“Laura VanArendonk Baugh’s Shard & Shield pursues classic fantasy visions of magic, alien creatures, and troublesome royalty. Its alien Ryuven are well-crafted, and similar enough to humans for empathy and dissimilar enough to be interesting. . . . Shard & Shield will intrigue readers with its world-building and complex relationships.”

Read the complete review in Lorehaven magazine’s fall 2019 issue.

Zettai ryouiki! I feel obligated to post the Evangelion opening. The show’s now on Netflix, but I don’t recommend it to noobs, partially because it helps to have context for the mecha-genre tropes they’re deconstructing, but mostly because it’s super WEIRD. Maybe bring a senpai with you.

Part of it is developing discretion over time. With social status for example, it is often a bad thing to chase, especially when people seek it in the form of fame and whatnot. But social status is also linked to reputation. Basically, what other people think and even feel about a person. When someone’s reputation, social status, etc is bad, it’s actually threatening because people will get treated poorly according to what everyone thinks of them. So if someone cares about social status, it isn’t necessarily about self importance, fame or riches. It can be because they innately sense the dangers of having a bad social status.

But exactly how to handle that is a skill developed over time. Instead of solely guarding one’s reputation, people also need to explore ways to survive and be happy even without that good reputation. A person could also over react whenever they feel their reputation is in danger, inadvertently ruining their reputation in the process.

Kinda agree with the idea of things happening because people are people, rather than ‘people are innately good or bad’. And ‘people do things because they are people’ does tend to be the perspective I write from. Even the chars most might point to as mainly good or evil at least have a semblance of cause and effect to them. But even though I don’t mind stories that represent the fight between good and evil, that seems way less actionable than stories that show people and situations for what they are. If a story shows people for what they are, then it can give people ideas for how to navigate difficult situations, or even invite the reader to put themselves in that situation and figure out better ways to handle it.

But a simple ‘we must fight the darkness’ story is not always going to be as useful. Most people will agree that we ‘must fight the evil!’ The more complicated part are the hows and whys and to a degree what people even consider evil in the first place. Like, one person reading a ‘fight the darkness!’ story could be motivated to get out there and fight on the pro choice battlefront, while another person would be psyched up to argue the pro life perspective. And many from both sides really think lowly of each other and consider each other ‘the darkness’…

The article you wrote draws some general life lessons from shields–though you wind up transitioning from shields into barriers. Is that appropriate? In part, sure, but a real shield of the sort used by the Vikings (let’s say), while it’s bulky and could maybe get in the way a little, it literally moves out of the way as soon as its owner drops his or her arm.

Likewise science fiction shields a-la Star Trek. Sure, “shields up” comes with disadvantages (no transporter use) but you can drop them in a second if you need to. Not raising shields in moments of doubt is considerably worse, if any strategic lessons at all can be drawn from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

I haven’t read Shard and Shield, but I presume that in your story, the magical shields can be dropped as easily as the science fiction shields in Star Trek. So they don’t form permanent barriers.

A barrier is a different kind of thing. A barrier, like a shield, can be intended for protection (like a medieval city wall) but barriers aren’t always as clearly for protection as a shield…well, at least not in the same way when talk about traffic barriers, etc. And barriers are ALWAYS up, with no easy way to bring them down. They’re quite different from shields in that respect.

In an analogy, having barriers up clearly can be destructive…but shields up isn’t quite the same thing as barriers up. The biggest difference of course, as already said, is one drops instantly and the other doesn’t.

This topic reminds me of something that doesn’t use the analogy of shields, but isn’t as far removed as you might think: Seat belts.

The lowly seat belt you strap across your body is there for those “just in case” moments when something goes wrong. A person hardly ever needs a seat belt, but if you do, you’ll be glad you took the precaution of putting it on. (Maybe like how the USS Enterprise would have felt if they had raised shields when the USS Reliant approached… 🙂 )

In Medieval times people rarely carried a full-size shield for “just in case” moments, but they might carry a small shield (a.k.a. a buckler) along with a sword. Which would a bit like a Middle Ages version of a seat belt–you don’t want to get ambushed along the road, but if you do, having your sword and buckler is much, much better than being totally unprepared.

It’s odd but true that some people used to argue in the days before seat belt laws became mandatory that having a seat belt is bad, that it can trap you inside a burning vehicle, or that being thrown from a vehicle might save your life. Well, actually, yes, it is possible for a seat belt to trap someone in a burning vehicle (which is why seat belt cutters were part of the Army-issued equipment I carried in Iraq and Afghanistan) and it is possible that not wearing a seat belt can throw you out of a vehicle in a way that saves your life (the latter happened to my mother, who rolled a Jeep with a fiberglass top–which became deadly shards that would have killed her–but she wasn’t wearing a seat belt and was thrown from the car, so that didn’t happen). But in fact, that’s exceedingly rare. Most of the time, the protective measure is far, far safer than not having it.

So really we go through a kind of calculus–is the protective measure worth having or not? In the case of seat belts, the answer is clearly “yes.” In the case of shields, ones that can be instantly dropped, the answer would mostly be “yes,” too. With barriers, when we realize we are talking about permanently changing something, we should be more cautious…and barriers not serving a positive purpose clearly should be removed. But even certain barriers are good…

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44266/mending-wall

I enjoyed reading that.