For some years, I avidly followed a certain political/cultural writer until finally – you know how it can be, between authors and readers – we drifted apart. I thought her commentary was simply declining. One symptom of this decline was an overabundance of the word serious. It wasn’t right or left or even right or wrong anymore: The new word – the only word – was serious. Our national diagnosis was a lack of seriousness and our national prescription was to get serious. Our leaders weren’t serious and they didn’t know how serious things were, but if everybody would just get serious we would all be serious and then things could finally stop being so serious.

I lost interest, but I had a thought: To be serious is not enough. And can’t a serious person be just as wrong as an unserious person and, in certain situations, even more disastrous?

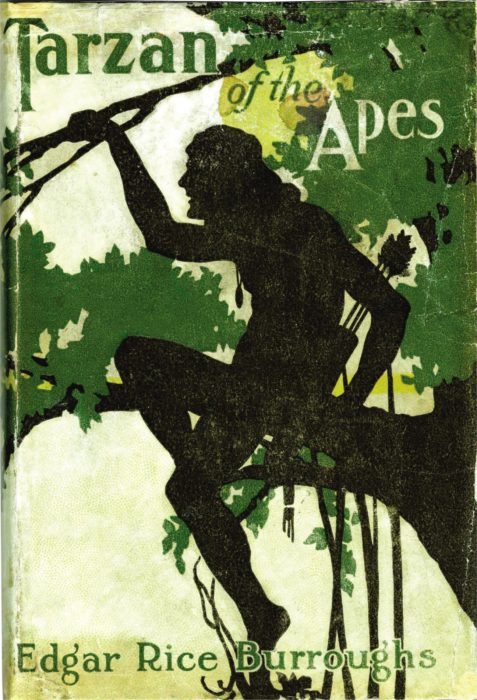

This principle can be applied to art as well as people. You may hear much of serious art or a serious work, but the phrase tells little of the real quality or worth of the work. My favorite example of this disconnect between seriousness  and worthiness is Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes. The most shocking thing about Tarzan of the Apes is that it is a genuinely serious book, a story written around ideas. The second most shocking thing is the book’s level of racism. Given the period in which Tarzan of the Apes was written, a certain degree of racism would not have been surprising; when racism is dominant in society, it is inevitably reflected in (some of) that society’s art. But even with that forewarning, the racism of Tarzan is surprising in its pervasiveness, in how deeply and how elaborately it is woven into the story.

and worthiness is Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes. The most shocking thing about Tarzan of the Apes is that it is a genuinely serious book, a story written around ideas. The second most shocking thing is the book’s level of racism. Given the period in which Tarzan of the Apes was written, a certain degree of racism would not have been surprising; when racism is dominant in society, it is inevitably reflected in (some of) that society’s art. But even with that forewarning, the racism of Tarzan is surprising in its pervasiveness, in how deeply and how elaborately it is woven into the story.

These two elements – the book’s seriousness and its racism – are not at all in contradiction. Indeed, if Tarzan of the Apes had been less serious, it would probably have been less racist. Burroughs might have still, in the appearance of a minor black character, invoked cheap, false stereotypes, but he would not have taken such pains to present thoroughbred English aristocrats as the highest human type. That was Burroughs’ elucidation of the theory of eugenics. Tarzan of the Apes revolves around nature v. nurture, the effect of environment and the effect of genetics; it is also wrong about nearly everything, from the truth of eugenics to the likely consequences of a childhood totally without human interaction. But books, like people, are not any less serious for being wrong, nor less wrong for being serious.

All of this emphasizes the essential ambivalence of what we call seriousness. Serious is more a description than a judgment, more an attribute than a virtue or a vice. To be serious is not to be good, or even to be deep, but the ambivalence is greater than that. Serious ideas, cogently presented, are as likely to be false as to be true, and some of the most serious works are also among the most malignant.

So if anyone, or anything, is commended to you as being serious, remember that this could mean seriously wrong.

There was a YA writer that I liked except for his tendency to describe everyone as “young.” Granted, as a YA writer, most of his subjects were young, but it was very annoying that that was all he had to say about them.