Safe Fiction And The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz

Some time ago I was talking with a group of friends, and the topic of “safe” fiction came up. Since two of these Christians are moms and the other is a school teacher, they had a vested interest in the topic. At one point, we began discussing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, primarily the film version so well-known today.

Some time ago I was talking with a group of friends, and the topic of “safe” fiction came up. Since two of these Christians are moms and the other is a school teacher, they had a vested interest in the topic. At one point, we began discussing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, primarily the film version so well-known today.

In most circles, this book and movie would be an illustration of safe fiction, the kind we want our children to read. After all, the story upholds the importance of home, the value of courage, heart, wisdom and honesty.

From Wikipedia:

Regarding the original Baum storybook, it has been said: “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is America’s greatest and best-loved home grown fairytale. The first totally American fantasy for children, it is one of the most-read children’s books . . . and despite its many particularly American attributes, including a wizard from Omaha, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has universal appeal.” The film itself is widely considered to be one of the most well known, beloved films of all time, and was one of the earliest films to be deemed “culturally significant” by the United States Library of Congress.

“Culturally significant” is an apt description, I think. The movie and book, in my opinion, prepared several generations to accept secular humanism in place of Christianity. A bold statement, perhaps, but not without grounds.

First, the author himself, L. Frank Baum, was a theosophist. From “What Is Theosophy”:

Theosophy teaches that all religions contain elements of the “Ancient Wisdom” and that wise men throughout history have held the secret of spiritual power. Those who have been enlightened by the divine wisdom can access a transcendent spiritual reality through mystical experience.

No wonder, then, Dorothy and friends arrive in Oz only to discover that the wizard, as the supposedly all powerful ruler (and therefore a God figure), is a fraud. No wonder in the end, good witch Gilda tells Dorothy she’s had the ability to go home all along, she just had to find it inside her. No wonder the Tin Man discovered he had heart all along, the Lion learned he had courage, and the Scarecrow, brains. Throughout the story, there is this strong thread—You can do it, you can do it, you can.

No wonder, then, Dorothy and friends arrive in Oz only to discover that the wizard, as the supposedly all powerful ruler (and therefore a God figure), is a fraud. No wonder in the end, good witch Gilda tells Dorothy she’s had the ability to go home all along, she just had to find it inside her. No wonder the Tin Man discovered he had heart all along, the Lion learned he had courage, and the Scarecrow, brains. Throughout the story, there is this strong thread—You can do it, you can do it, you can.

And what a popular message that is today. Self-help seminars, books, infomercials, all proclaiming this belief in the human spirit. How many athletes say something similar in wrap-up interviews! We just had to believe in ourselves.

So now in western culture we have Man, clawing up behind Satan, trying to replace God. In part because of a piece of “safe” fiction.

There were, I’ve heard, some objections to the movie when it came out—because it had witches in it, I was told. So if the good and bad witches had been replaced by good and bad shoe salesmen, the problems would be taken care of?

The search for safe fiction can be a dangerous, dangerous pursuit. Too often those engaged in the quest are looking for whitewashed walls, all the while oblivious to the fact that behind them may lie a tomb.

This article first appeared, minus some editorial changes, at A Christian Worldview of Fiction in June 2008.

– – – – –

For those in the US celebrating Memorial Day, may you enjoy your holiday in whatever manner you choose.

I’m sorry, but I have to call you on this. You’re really reading into the Wizard of Oz motives and connections that aren’t there.

I don’t think Oz had much of an effect on self-reliance as a substitute for God or as promoting secular humanism. Self-reliance has been a part of American culture before Oz, and is hard to isolate the sources of. You have the Protestant work ethic, you have the Transcendentalists, you have Horatio Alger Jr, and probably many more influences than any of us can think of. I don’t think Oz particularly pushed that enough to blame it specifically or view it as unsafe. It’s just an American fairy-tale; one that uses the old models of the Grimm works and sets it in cornfields and other odd locations.

The theosophy I don’t know. There are books that state theosophy explicitly or use it heavily in its themes; Lord Dunsany’s faerie tales come to mind. Charles Williams ironically is a heavily theosophic writer, albeit a redeemed one; he was a former theosophist, and his novels are full of that imagery. I’m not sure though reading Oz you can make the claim its influenced by it in any way, any more than Edith Nesbits works were.

I think again you are using an example that overstates the threat the work has. A better example would be Gregory Maguire’s Oz retellings, like Wicked. That has serious, harmful issues about sexuality and is often consumed by teens in the same manner that they now consume Frozen. I think that its better to make the case about popular works that deserve critical readings; overselling the threat of other books works against your argument.

What???

This interpretation is ridiculous, and shows the dangers of looking for demons everywhere – you’re sure to find some that don’t exist.

The meaning of the Wizard of Oz is well known. It is an allegory on monetary policy and satire about the political environment of the time. Baum was a supporter of bimetallism (a currency based on both gold and silver), a monetary policy that would cause mild inflation, and so help debtors. The primary champion of this policy was William Jennings Bryan, who gave the famous “cross of gold” speech.

The golden road represents the gold standard that leads to the Emerald city (Washington DC) which in the book is not actually emerald, but rather everyone is required to wear green goggles to make everything appear green (this was commentary on how politicians believe that if everyone pretends things are a certain way, then they are that way – possibly a reference to fiat money). The Wizard of Oz represents the President of the United States, who appears all powerful, but actually is just a conman. Which is why the mighty wizard with a man behind the curtain has been cartoonist short hand for puppet politicians ever since.

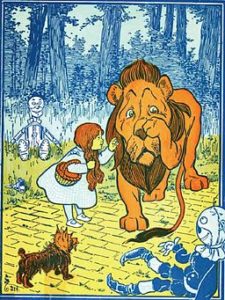

Dorthy herself represents America (who is traditionally depicted as a young girl), while her companions represent the coalition Bryan tried to put together. The farmer (the Scarecrow) who is told he’s stupid and uneducated, and the urban working man (the Tinman) who is treated like an unfeeling machine. Baum through his story suggests that the opposite is true, the Scarecrow comes up with all the ideas, while the Tinman is the most emotive of the group.

The Lion is William Bryan himself, and is Baum’s way of encouraging him to find his courage and run boldly on the bimetallism platform instead of threading a more moderate path.

The Wicked Witch of the East represents the business interests of the east coast imposing their will on “the little people” (the Munchkins). The Wicked Witch of the West is the drought afflicting the farmers (and driving them into debt, which is why they supported an inflationary policy). Hence the Wicked Witch of the West being vulnerable to water.

Dorthy’s silver slippers (changed to ruby in the movie) provide the true method of her getting home, and not the fake Wizard’s power, nor the gold road.

This is the overwhelming accepted hidden meaning of the Wizard of Oz.

Dan, as I noted below, literary interpretation is not even as stable as science, so it’s surprising to read that you think this understanding of the story is set in stone. Not everyone agrees:

I’ll add, for the sake of my point in this article, the question to ask is, Where is God? Even if this was a political allegory, clearly there’s no place in it for the Church or for God. All things religious would, in essence, have nothing to do with the economics of society.

It is this kind of thinking that I believe slips into our psyche unchallenged because it is unnoticed. Mostly what I’m advocating is, Start noticing.

As long as we think something passes the “no harm” police, we let our guards down and no longer think what the piece might be saying or what example the characters might be modeling. It’s then that we’re vulnerable.

When we’re on the alert and see even the absence of God, we can counter it—not by going on crusades to have the book removed, but by having discussions like this one that call attention to the worldview of the book in opposition to the worldview of Scripture.

Becky

The point of the Scarecrow, the Tin man, and the Lion’s search for the things they wanted was not that ‘it was inside them all along’, or ‘they had to believe in themselves’, it was that they were looking for the wrong things (and they didn’t even realize their error in the end, either, they went on thinking it). The scarecrow thought he was stupid because ‘he knew nothing’, but he was really quite intelligent, and the ignorance that comes from being very new can easily be mended by learning things. The tin woodman thought he was ‘heartless’ because he literally was, but it had no effect on whether he felt and showed compassion and tenderness. The lion thought he was a ‘coward’ because he always felt afraid, but the important thing isn’t really to feel not afraid, it’s to do what you need to do anyway, which he always did.

And all of those things are _good_ lessons.

And seriously, the way people pick on the wizard makes me feel sad. He doesn’t have to ‘represent God’ if you don’t say he has to. If you wanted to make it a political theory, you could say he represents a bad government (a tyrant, or some such thing), and that the point of the story is that evil men only hold sway through a lot of politicking smoke and mirrors, and that the way to get to the heart of things is to stop playing along with it all. And another point could be that the government can’t fix everything, and even when it says it does it often isn’t actually a fix.

There are something like seven perfectly plausible and perfectly independent theories about what this book ‘represents’, and somehow I doubt that Baum stuck all of them in. I doubt he put any of them in. It’s just a story with imagery that is very easy to match to things, with a little creativity.

Juliet, certainly there is nothing wrong with home or courage or compassion or brains. That’s really the point, though. “Safe fiction” is that which isn’t offensive on the surface.

The only offense, in my view, is that these characters could find all they needed apart from God.

That theme has captured Western society. It’s an anti-God philosophy and a gateway to all kinds of false ideas—Buddhism and Eastern Mysticism, for example. The whole concept of becoming enlightened by looking within is played out right here in this story.

Do we have to run screaming from the library or start a campaign to burn the books? That would be horrible and completely miss the point. It’s not this book or that book or any other book that I’m opposing. In fact, I’m not opposing anything. I’m challenging readers to think about what we read instead of letting ideas slip past our awareness because someone has told us this book is safe.

People can disagree with my interpretation of this book if they want, but I hope they don’t disagree with the central point I’m trying to make.

Becky

This is the problem with your analysis. Most fiction does not mention God. Most fiction leaves an empty hole in the place were God and religion should go. Not because authors think God unnecessary, but because authors fear to talk about a subject that might lose them readers if they promote a view of God that disagrees with their reader’s view.

This is one of the reasons I enjoy books by authors such as C.S. Lewis or Brandon Sanderson. Their books are filled with religion. If you had decided to point out the absence of God from The Wizard of Oz and presented it as a missed opportunity, I would have been fine with it. Except to wonder why The Wizard of Oz was singled out.

Instead you take the absence of God and accuse poor Baum of trying to tell people that God is unnecessary when there is no evidence that he believed such a thing. (There is evidence he thought correct religious doctrine to be unimportant, but that’s not the same thing. He was an Episcopalian who joined the Theosophy movement, suggesting that he thought non-Christians such as Buddha had valuable spiritual insights. That’s not the same as “you don’t need God, you can do it yourself.”)

I see no evil in the story of the Wizard of Oz and I am confused as to how the absence of one good in this specific story means that we cannot enjoy the other goodness in it.

Then perhaps your analysis is actually just another discussion of the old problem of ‘Can a book be good at all without God in it?’ Which is a really big, really old discussion. 😛 And like Dan said, a lot of books and other forms of story media do the same thing you are objecting to in ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’, it isn’t really an exception of any sort.

You’re possibly being even more exclusive of what safe books are than ‘A book can’t be good without God’, by saying that a book cannot be really safe and good unless it makes it clear that the good things people do and are originate from God and not themselves. So that means even more media doesn’t fit, like, Peanuts, LotR, Anne of Green gables, Wrinkle in Time, The Sound of Music, Little Women, etcetera.

Is that what you’re driving at, or have I got it wrong again?

I do agree that you should examine the things books say, regardless of whether people tell you the book is ‘safe’ or not, yes. That is a fair and good point.

But I don’t really think that in order to be discerning you have to assume that an untruth is meant even when a story could be interpreted another way.

There is a big difference between the book and the movie on this point.

In the book, the Scarecrow thinks he’s not smart, but is always coming up with the brilliant plans. The Tinman doesn’t think he can feel, but is the most sensitive of the bunch (feeling sorry for a bug he stepped on, for instance). The Lion thinks he is a coward, but constantly faces the dangers with bravery.

The movie loses this aspect. The Scarecrow really is stupid. The Tinman doesn’t act with feeling. The lion actually acts scared. It isn’t until they get to the Wizard that they are told they already have it. It is then they begin acting like they’ve got it.

In the book, I don’t recall that being stated, but the Wizard gives them something to make them believe they now have it, when to the reader it is obvious they’ve had it all along through the whole story.

The movie has more of the feel of the “Power of Positive Thinking” concept. The book, not as much, though one could interpret it.

That said, despite the various interpretations, yours is a valid way of looking at it. However, I’d suggest at best the book and the movie supported a secular culture in that regards, rather than single-handedly influencing a generation of kids into that philosophy that otherwise wouldn’t.

Indeed, one could posit that a core teaching about writing supports a secular view of man. Writers are told that a satisfying story is when the protagonist is active in resolving the conflict and climax. No duex ex machina endings. No passive victories for the hero. The resolution has to come from within the protagonist.

So are modern stories by default, based in secular philosophy because the protagonist at some point has to rise to the occasion?

Agree, Rick. This book is not alone responsible for humanism. I don’t think it should be downplayed, however, as a tool by which ideas are disseminated.

Becky

Looks like my comment was eaten, so I’ll try again.

I’m wondering why we’re supposed to be so scared of theosophy. It sounds pretty much the same as CS Lewis’s Tao. And why are we making such a bogeyman of secular humanism? Most of it aligns with the Lewisian Tao, being mostly about helping other people or at least not being a turdbucket. Yes, it’s framed in terms of willpower rather than God looming over you, but I don’t find much wrong with that.

Yet if God is real and active and the supreme Best in the universe, it would be rather offensive to Him to leave Him out of the whole “helping people” thing.

Also without Him, “helping people” ultimately becomes a rather vague and confusing activity. After all, you can “help” a man by giving him money. You may also help him by taking him to court and locking him in a small room.

Sure, you can be “helping people” while disbelieving in God. But you must steal from certain ideas about God and what He wants in order to go about “helping people.”

So? Let ’em steal it. “He who is not against us is for us” and that jazz, and most of the opposition comes from way and means and not intentions.

Notleia, I don’t think we’re supposed to be scared of any idea, Theosophy included. That this philosophy looks to Man and not God is clear, though, which makes it false. I don’t know about you, but I’m not scared by something I know isn’t true. If someone says, There’s a lion in the street, and I know there is no lion in the street, I’m not scared at all. On the other hand, if I think the only lions that exist are caged in the zoo and stroll out my front door only to confront a lion, well, that is a problem.

I suggest that’s what happens when we declare fiction, any fiction, to be “safe.”

But I suspect you’re thinking there’s nothing wrong with looking inside for enlightenment. Whether Theosophy is similar to Lewis’s Tao, I couldn’t say without more study, but I’m fairly certain Theosophy stands in opposition to Scripture. The idea of Humankind reaching to the heavens by reliance on his own abilities is precisely why God confounded language and scattered those who were teamed up to bypass Him.

God is the Source of all things and to pretend Humankind is, simply sets us up as the idol of our own hearts.

Becky

Okay, I am exaggerating, but the tone just comes off as mildly paranoid, or why should we be so cautious around something as harmless as humanism? If the only problem is not in sucking up to God enough (and I need some citation where God is petty enough to be offended when people do good stuff without Tebowing about it), then I can live with that, partially because the Calvinist tone of needing God looming over you to make you be good just grates on my free-will nerves.

That’s the thing about false teaching, notleia. It looks harmless—the whole wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing thing. Looks innocent but will cost you your eternal lives.

But you want citation. I’d say pretty much the whole Old Testament is about God insisting that people listen to Him, obey Him, know Him, and worship Him—and Him only.

I’ll start with the Ten Commandments, though:

And here’s what’s behind this command:

So in reality, when we bypass God and say things like, The courage is mine, The compassion is mine, The ability to think is mine, The ability to save myself is mine, we are bowing down (Tebowing, in your terms 😉 ) to ourselves. We are giving to ourselves what God alone deserves.

Becky

Nah, man, if the major terrifying thing about humanism is that it’s not exactly Christianity, then it’s pretty harmless. Fewer turdbuckets in the world, even if they’re not specifically Christian = everybody wins.

But to my thinking, God doesn’t need us to maintain His dignity and/or awesomeness. It’s a nice thought, but I can’t really believe that Tebowing makes a person more moral, because it’s easy as heck to make humble mouth-sounds your head no longer believes.

We may be confusing issues here.

Humanism is of itself not anti-Christian. There are Christian humanist.

Secular humanism is humanism based upon secular values. Instead of God’s values being the basis for humanitarian efforts and motivation, man’s own relative and communal values become the basis. Secularism is opposed to Christianity because it puts man in God’s position: providing the moral and values basis for our existence. The humanism between the two can differ as well due to the different values of the two systems as well as Christianity is more absolute values based upon God’s revelation, while man’s is relative and in flux.

Theosophy is a philosophy based upon the idea that being and existence can best be understood through revelation. In the Early Church, the term was the equivalent of a theologian. So early on it was restricted to God’s revelation through Jesus Christ.

The more modern version gained a foothold in philosophy in reaction to Aristotelian philosophy, and the basis of revelation used widened to include various religions including more gnostic sources. It isn’t secular in the sense that man becomes the measure of all things, but definitely left the realm of Christianity in what revelation to use as a basis. Some of it became more esoteric, where meditation on something could reveal its true being. But in theory you can have a Christian theosophist if they stick to Christian revelation (Bible) as their source. But even then, it is a philosophy, not a theology. Properly speaking, it is a philosophy based upon a theology, or plural theologies.

Theosophy has little to do with humanism, though a person could hold to both. Not really secular, though usually not Christian either.

The book, as I mentioned, differs from the movie. In the book, those qualities are there all along. There is no explanation that I recall of how they got there (man’s goodness or God’s infusion?) So, really, one could interpret this in many ways. For instance:

The Wizard of Oz is a popular pastor. Church members come to hear him preach and do miracles in hopes of gaining a quality they hope to have. A good pastor will direct them to realize they already have it through the Spirit that lives in them, for they have no power within themselves to impart such qualities. Our time here is in preparation for when we are ready to “go home” to heaven, though unlike Dorothy, we generally don’t have control over that, though we could through suicide. But Christianity says to wait until God clicks those heels for you.

Point being, who knows what he intended, if anything, to say. Disney’s movie is more secular based since they don’t have those qualities until the Wizard tricks them into believing they do. It is the belief they now have it that creates the qualities in them. More of a secular basis, where as the book could be interpreted secularly, but not necessarily.

Anywho, more food for the discernment mill.

I found myself nodding in agreement while reading much of this article. The politics/history went over my head, but even as a child I could detect the harmful humanist overtones of the book and movie. It’s one of the reasons I’ve never felt an affinity for Oz. That said, the Wicked Witch on the TV series Once Upon A Time is deliciously creepy.

Sharp replies. I’m glad to see each of us putting thought into this.

My first idea was, “If you were to rewrite the plot with Oz clearly representing the Father, and their interwoven lives as a wonder journey to Him, what would that look like?”

I’m not familiar enough with the book to be as definite as I’d like to, but I wondered if the text really forces Oz to be a God figure. I can see how if you read it that way it would be at the very least insulting toward Him and blasphemous.

It might not be the tidiest and most broadly accepted, but why couldn’t Oz be simply a specific king (for the sake of argument, say, King David), if what you are responding to is Oz’s rulership? Another try: could Dorothy be a Christ figure?

Lots of possibilities.

I think it would look a lot like Pilgrim’s Progress.

As for the Wizard of Oz, he is first describe like this:

The language, in my thinking, is very God-like. Not to mention that Dorothy is directed to him as the one who can help her get home.

Later in the descriptions, one of the people living near the Emerald City responds to the Scarecrow:

Later, when the Lion answers the Wizard’s question about why he should give him courage, he says

These are all descriptions that fit God.

But in thinking about the story, another way of looking at it would be to ask, Where is God? In not the Wizard, then where is God? Where does He come into the story? In fact, it’s unlikely anyone could find another God figure or any indication of God moving behind the scenes unseen. He isn’t credited with bringing Dorothy’s house down on the Wicked Witch of the East. Rather, as she says, It just happened.

Clearly, literary interpretation is not science. It has a great deal to do with the reader and interpreter as well as with the writer.

But for the sake of this article, I’d say The Wonderful Wizard of Oz does not point to a Christian worldview. Dorothy, as it turns out, doesn’t need anyone else to find her way home, and her companions don’t need anyone else either. In other words, they aren’t dependent upon God. They can get what they need apart from any “higher power.” That’s not an interpretation. That’s a summary of the resolution.

Did L. Frank Baum write this ending—in fact, this beginning and this middle—with the intent to belittle God and elevate the human capacity to reach perfection? I think it’s only fair to say, no one knows for sure. We do know he became a member of the Theosophical Society in 1902, two years after publishing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Theosophy is, essentially, a religious philosophy seeking “hidden knowledge or wisdom that offers the individual enlightenment and salvation.”

It’s not a stretch to see Dorothy being guided to do exactly that same thing.

Becky