Zootopia: Fantasy Salvations For Creatures Of Fear

Disney’s Zootopia feels like two movies blended into one movie.

Both movies are about Judy Hopps, the oldest daughter in a (necessarily large) family of carrot-raising rabbits. Her Disney dream: to become the first bunny police officer in her all-animals world, despite all the other animals insisting a bunny could never become a cop.

The first movie is about Judy’s struggles against bigotry, both her own against others and others’ against herself, and her “salvation” through repentance and forgiveness.

The second movie is about an all-animals society struggling with collective prejudice, most of it by former prey against former predators. This society discovers a shared and secular “salvation,” thanks to the priestly influence of its own righteous popular culture.

That first movie was great. That second movie was full of oh-heck-no.

So Zootopia reflects an excellent microcosm of popular culture in general: moments of awesome God-granted grace, mixed with nearly equal amounts of oh-heck-no.

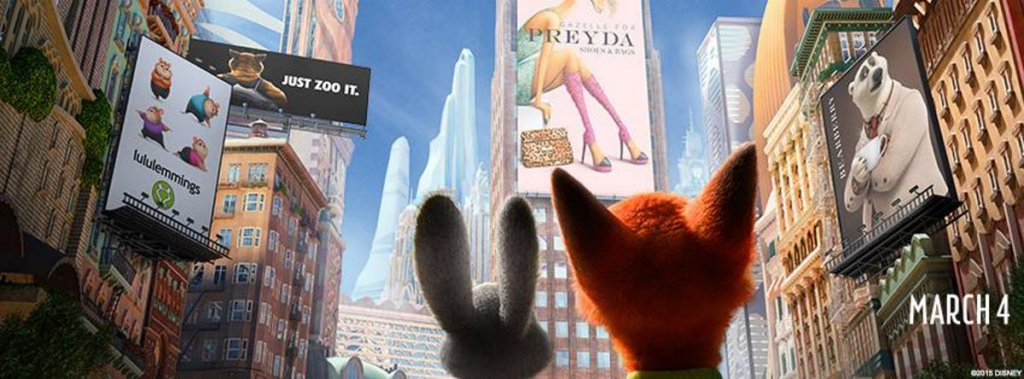

Zootopia is visually splendorous. In this unnamed land, only walking, talking mammals1 live and work. Animals have their own culture, history, education, government, families, technologies, and comical(?) addictions to their smartphone apps.2

Zootopia is visually splendorous. In this unnamed land, only walking, talking mammals1 live and work. Animals have their own culture, history, education, government, families, technologies, and comical(?) addictions to their smartphone apps.2

Judy Hopps, our perky bunny star, wants to be a police officer, a job naturally reserved for larger animals. This is a Disney movie, so Judy works to follow her dream. But this time she achieves her dream in 15 minutes of story-time. Then she learns what sorts of challenges come after achieving her dream—a theme other Disney films don’t often explore.

For a supposedly light animated film, Zootopia’s makers aim higher. They want the film to respond and subvert not only animated film narratives, but to racism fears themselves.

This is why several friends of mine, including Christ and Pop Culture colleagues, praised the film’s approach. They found its themes uplifting, perhaps even healing amidst ongoing racial wounds. That is why I can also aspire to review this engaging film on these terms.

Secular ‘sin’: non-evolved fears

I was doubly engaged to find that some animals have prejudices against other animals. This is especially true of animals who were once prey and those who were once predators.

“We evolved!” a child explains in the opening act.

This is fine for fantasy world-building. But it’s unrealistic if the story aims to confront real-world racism (and it does). Here is the Christian’s first objection: no, we haven’t evolved beyond anything. In fact, deep down we are all predators at heart. Moral law written on our hearts condemns us.3 Civil law restrains and punishes us.4. Only Jesus can save us. “Evolution” of this nature is not realistic. It is an escapist, shallow fantasy.

If Zootopia’s world is meant to resemble ours (and it is), this breaks the analogy within the first five minutes. This “we evolved” bit—and the story assumptions that follow—frames the world in the colors and language of secularism. But then it attempts to explore things like racism with honesty. You can’t do that. Racism, and the associated evils of humans hating other humans, is an evil. It is a spiritual problem. Evolution-language will not help us deal with it honestly. In fact, calling this evil “non-evolved” minimizes the great evil we face.

But Zootopia is a story. And very few stories can resist showing an actual, absolute evil to defeat. After all, in this world, we see genuine evil and fears. Peaceful animals who were once predators are actually going insane and attacking other animals. What’s the cause?

I must give a spoiler. In Zootopia, the only reason for predators going insane is: poison flowers. That’s it. Remove the poison flower, find a cure with science, and you remove the sin. Then you can present people with an objective Fact: that only an accident made them crazy. At this point they can defeat the true villain of the story: fear itself.

Given its own aspirations, Zootopia suggests very few real people are actually evil. Most people are simply confused and fall prey to fear. And isn’t fear the only evil to worry about?

Well, that’s a popular idea. But it’s a sentimental one, in fantasy and in reality.

Secular salvation: popular culture as messiah

Now our problem of racist evil has been redefined. It’s not “evil.” It’s reactionary fears that are so last-stage-of-evolution. Who will rescue us from this body of cultural backwardness?

Unfortunately the story’s first answer seems to be: popular culture. Really. In the form of the Shakira-like gazelle-pop-star voiced by Shakira. 5 Shakira does very little. She sings during a montage and is seen on one character’s smartphone app. I wondered if this figure might play into the plot? And she does—ever so briefly. She appears in a news interview urging animals to reject fear and embrace the harmony that Zootopia is all about.

So: legalism and moral instruction—through popular culture. Try harder. Don’t fail, ever.

Then at the film’s end credits, all our heroes end up at a big Shakira concert. In this rather Shrek-sequel-like staging, everyone has a happy ending and parties hard to the tune of an absurdly catchy yet also absurdly lyricked pop song, “Try Everything.”6

So: final redemption, “glorification,” and vision of paradise—also through popular culture.

I love the idea of popular culture. It was God’s idea, after all. He wanted humans to work to create culture, and rest (even party!) with popular culture. But we must be honest about what popular culture now is and is not. Popular culture will not save us. It’s not a paradise for “evolved” creatures. It’s certainly not a priestly influence. And even a real priest isn’t subject to such fawning hagiography as Zootopia gives to the idea of popular culture.

Spiritual salvation: repentance, forgiveness, reconciliation

All of that counts for a false gospel of “salvation.” This is a salvation not from sin but from non-evolved fear. It’s not by a good sacrificial hero, but by sacramental popular culture.

This themes clash with Zootopia’s better “salvation”: Judy’s journey from her own dreams, to disillusionment, renewed ambition, and victory. Meanwhile she is also struggling with her own prejudices, especially given her sad memory of being bullied by a boy fox. Are her parents right that predators are, if not bad people, just not the best people to be around? Maybe she should be extra careful. Maybe she should carry this anti-fox spray, just in case.

One day Judy, stuck on the meter-maid beat, meets an adult fox, Nick. He behaves just as craftily as she’s been taught to assume. But when an otter disappears and Judy is assigned to the case, she and Nick are forced to work together. Spoilers: They soon become friends.

Then Judy is put in a position to assume the worst about predators in general. She’s winning—realizing her dream! She shares her viewpoint with the city. Then returns to her friend Nick, who can’t believe what he’s just heard her say about all predators. Like him.

More spoilers: By the end Judy confesses her sin and gives Nick an unqualified, tearful repentance—not just an apology, but repentance. And Nick forgives her. And this is the story’s best solution to actual prejudice: not vague notions such as being “evolved” or only fearing fear itself, but confessing the sin of prejudice and seeking Nick’s forgiveness.

Zootopia is the top animated film of 2016. It’s bound to have a sequel, and I would love to explore more of this animal world. But if the next story wants to draw parallels to reality, it must explore more of what makes these animals—well, more like real humans.

- Zootopia does not show us lands of reptiles, fish, birds, or insects. Perhaps we will meet these societies in a (rightly expected) Zootopia 2? ↩

- If I had the chance, I would like to ban two elements from all animated films: smartphone “jokes,” and so-surprised-a-character-just-poops “jokes.” ↩

- Romans 1. ↩

- Romans 13 ↩

- Shakira is in this movie, Zootopia, which stars Shakira as herself (Shakira). Songs by Shakira. ↩

- Presumably this means “try everything except acting like a predator and chasing prey.” ↩

Ah, you nailed down what vaguely unsettled me about that movie. I just couldn’t figure out what it was. That gazelle chick is the high priest of acceptance and tolerance. That was the meta narrative–tolerance–even for prey and predators. Intolerance of different animals was a horrible evil.

Now that we’ve tackled racism, I suspect ZOOTOPIA 2 will be about the evils of opposing inter-species romance.

Good points — I hadn’t noticed that second, negative aspect of the movie either of the two times I saw it, but you make a good point about the mixed message.

However, I would argue that there is real evil in the movie, in the form of the [no spoilers here] villain and their accomplices, and that their evil is not healed or redeemed by the “let’s keep trying and have no fear” message but is punished with arrest and imprisonment. So there is a final judgment, so to speak, even if it’s the kind of watered-down form of earthly justice that assumes a Law and a moral code without having any philosophical basis for it.

I also didn’t get the impression that Gazelle’s “why can’t we all just love each other” speech to the media and her hip-shaking pop tunes were actually affecting the outcome of the plot or suggesting that pop culture will save us. Nick and Judy saved the day by exposing the villain’s scheme; Gazelle’s appearances were just window dressing (and, thanks to the app, part of a running joke). That’s not to say that the movie offers any better solution to the problem of evil than “loving the same things will bring us all together,” but that’s by no means a specifically Zootopian problem….

I agree the Gazelle inspirational speech and “paradise” concert didn’t affect the outcome. But they did represent the untarnished ideal as contrasted with the “fear of the public” problem. In other words, the problem is limited to the news media and people in general. But popular culture songs and performers are Socially Conscious. I would dislike this simplicity if it were a pastor it spiritual leader playing a similar “icon” role.

Ah, I see. If Gazelle had been among the “prey” animals who expressed fear about their future, or if there were more than one pop culture icon represented in the film, the picture would look very different, agreed.