‘The Apocalypse Door’ Opens on Spiritual Thrills

The world around us contains more substance than is registered by our senses. The intangible spiritual realm is present and powerful. It teems with life … and with death. Christians know this better than most, and scriptural passages such as Ephesians 6 exhort us to never forget it.

So when the cosmic powers of this present darkness hatch diabolical plots, who on earth’s got humanity’s back? Who’ll stand up to Satan’s schemes? In evangelical fiction — as exemplified by the inimitable Frank Peretti — the spiritual SWAT teams tend to be headed by small-town pastors or recovering cynics who collaborate with martially-adept angels. In such stories, prayer is portrayed as the ultimate weapon, and the protagonist’s relationship with God becomes the primary determinant of his or her spiritual strength.

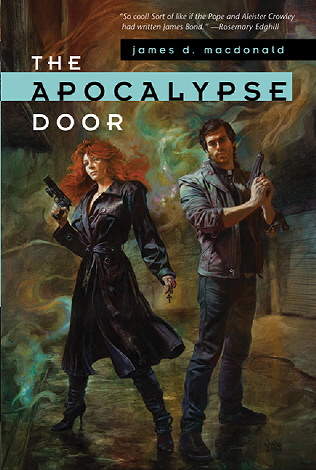

In Catholic fiction, things work a little differently. Enter Peter Crossman, modern-day Knight Templar and protag of James D. Macdonald’s The Apocalypse Door. This novel — along with several short stories coauthored by Macdonald and wife Debra Doyle and collected in The Confessions of Peter Crossman — is a cross between the James Bond, Indiana Jones, and Brother Cadfael franchises, set in the hardboiled detective genre, and seasoned with dashes of Hellboy and Constantine.

Who said it’s possible to have too much of a good thing?

As one of only thirty-three warrior-priests of the Inner Temple — that elite covey of Templar Knights unknown to even their secret-society compatriots — Peter Crossman is tasked with protecting holy places, the travelers therein, and artifacts of supernatural significance. To carry out this mandate he’s equipped with considerable resources, but none so effective as himself. Macdonald brings his extensive military experience to bear upon the verisimilitude of his plot, no hurdle of which is too-easily cleared. You will believe that Peter Crossman deserves the title with which he’s been endowed. You will believe it even when, by the end of the story, he slumps before you shaken, battered, fatigued, and desperate.

The breathless action begins in Newark, New Jersey, where Crossman’s been charged with infiltrating a suspicious warehouse by his superiors in Chatillon, France. Sounds mundane, you say? Not with the way Macdonald writes. The man is a magnificent wordsmith — his descriptions concise and punchy yet precisely evocative, his action scenes blocked and paced with expert care and ferocious energy, his dialog dancing with deft one-liners. Of course, the plot itself doesn’t depend on stylistic flourishes: its stakes swiftly swell to cataclysmic proportions, entangling our heroes in a labyrinthine conspiracy to fast-track the End of the Age.

Let me just get this out in the open: I loved this book. I could read it all day, every day. It’s immensely entertaining. From Crossman’s contraction-laced slang supposedly translated from the Latin, to his snappy banter with his assassin-nun comrade — Sister Mary Magdalene of the Special Action Executive of the Poor Clares (!) — the Rule of Cool is adhered to hard. And yet behind the novel’s escapism there lurks a spiritual sobriety that sets it apart from your run-of-the-mill urban fantasy. Only in a Peter Crossman novel could you read a sentence that said “I [sprinted across the ground] like lust through a teenaged heart” and not bust out laughing.

You see, Crossman is an actual priest. As in: he’s celibate, he gives and receives confession, and he administers absolution to his enemies after shooting them. This is not portrayed ironically. Twin epigraphs open the novel: the Catholic Act of Contrition and John 8:44. And throughout the duration of the story that follows, sin is presented as a serious problem. It’s real, pervasive, and dangerous. It can’t be ignored. It must be dealt with, confronted.

Of course, since this is Catholic fiction, the in-world means for confronting sin seem rote and disconnected to this Reformed reviewer. Crossman must always remain conscious of his state of grace, lest he perish with unconfessed sin and let slip his salvation. When opposed by demonic forces, he relies on the power invested in objects such as crucifixes and holy water instead of going directly to the Source of that power through prayer. This formulaic approach leaves little room for an exploration of Crossman’s actual relationship with his God.

His relationship with sin, however, gets a more thorough examination. The novel’s numbered chapters alternate with flashbacks chronicling Crossman’s dark past as a CIA operative in South America — an account which predates and sets up his conversion to the faith. Macdonald does something thematically gutsy with this account — something that may offend the sensibilities of those unconvinced that God works through all things for the good of those He’s called according to His purpose — but something that, in retrospect, I respect a lot. It demonstrates a level of confidence in the reader rarely equalled, in my opinion, by evangelical authors.

The Apocalypse Door flings open a rousing-yet-religiously-grounded entryway to the spiritual-thriller subgenre. If you love the idea of secret-agent priests and action-girl nuns battling Peretti-esque perils while respecting ecclesiastical dictates, then this is a knob you need to turn.

Wow. Reading this review was a series of smiles and what? and no way! moments.

This justifies the conviction that I’ve always had since childhood that Catholicism is simply way cooler than Evangelicalism.

You could always try something between those ends of the spectrum, like what I’m trying, something Protestant but more high-church like Methodists or Presbyterians. It’s different but interesting, especially if they’re musically inclined.

Nice review, Austin.

Perhaps. And yet, “Intrepid seminarian dispels intangible malign forces with dynamic prayer and three supporting Biblical references, then retires to local microbrewery for pint of stout and post-mortem review with faculty and classmates” doesn’t carry the same zing as “Warrior-priest bashes in heads, dispenses one-liners while battling demonic plot to fast-track end of world.” 🙂

I think Catholic lore, historical and otherwise, has a distinct physicality that lends itself to action-oriented stories, and it brings a wealth of symbol and metaphor largely discarded by the Protestant tradition.

You can certainly tell a rollicking tale with a Presbyterian protagonist, but you begin with a different tool box.

Oh, I wholeheartedly agree regarding the symbolic physicality of Catholicism. That’s the reason you almost never see Protestant clergy depicted as being useful in Hollywood films — when there’s a demon to be exorcised, a confession to be heard, or advise to be dispensed, the visual storytellers turn to those spiritual shepherds bedecked in robes and clerical collars, the ones who perform rituals and recite incantations, the ones who fit in a rigid hierarchy, the ones in uniform. Without such visual cues, spirituality would be so … you know, spiritual. And the medium of film is ill-suited for battles not against flesh and blood.

Or, from the Catholic perspective… “Show me your spirituality without physicality, and I will show you my spirituality by my physicality.” 😀

This book sounds perfectly suited to my tastes, and has been moved to the top of my wish-list. Thanks for reviewing it! Up until this post I wasn’t sure whether Speculative Faith avoided specifically-Catholic fiction.

Admittedly, I haven’t read the book, but this criticism sounds more like a theological criticism than a literary one. I’d love to hear the reactions of both a Catholic and a non-Christian to the same elements of the story. 🙂

SpecFaith is an equal-opportunity reviewer! We even review novels written from a *shudder* SECULAR perspective. And if we can manage that, Catholicism should be a cinch. 😉

Of course, by “we” I mean us. You and me. Anyone can submit fiction reviews to SpecFaith. And, as you’ve no doubt noticed, we need all the help we can get to comprehensively catalog every title that can reasonably fit under the heading of “speculative faith.” Personally, I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to Catholic fiction. The Peter Crossman series is the first of its kind I’ve stumbled across. Do you know of anything similar that you could recommend or even review? If so, I’d encourage you to do so.

Regarding my reaction to Peter Crossman’s formulaic approach to spirituality, it’s most definitely a theological criticism. 😉 The story itself isn’t diminished in the slightest by this “Catholic physicality”; on the contrary, it’s likely rendered more vivid thereby. But since the majority of SpecFaith’s readership is (as far as I’m aware) Protestant, and as the novel purports to unfold in this world, at this time, within this reality (aside from the obvious fantastical and secret-history elements), it’s important to me to point out that I don’t think it paints a picture of a healthy relationship with God, if only so that like-minded readers won’t be surprised when they arrive at the same conclusion.

Well, I don’t know of other works that are in the same adventure-fiction category, but Michael O’Brien has written several speculative books about the apocalypse from a Catholic perspective. The most notable of those is Father Elijah. While it has some adventure elements, it focuses very heavily on the invisible spiritual struggle between a Carmelite priest and the Antichrist for the fate of the world.

Along the same lines there is also Robert Hugh Benson’s 1907 SF novel Lord of the World, which pits a technologically advanced society devoted to the “Religion of Humanity” against the persecuted Church.

I’d be happy to contribute a review or two.

One question on that, though. As written, the Speculative Faith statement of faith isn’t compatible with Catholic theology. It appears that the statement of faith is only intended to apply to regular columnists, not occasional reviewers, though. Is that correct? As you’ve probably surmised, I’m Catholic. 🙂

Excellent. While I may not agree with the theological assumptions behind the criticism, I certainly approve of being direct in aiming theological criticism. 😀

Yes, the SpecFaith Faith Statement applies only to regular writers — who currently include Rebecca LuElla Miller, R.L. Copple, John Otte, Shannon McDermott, and myself.