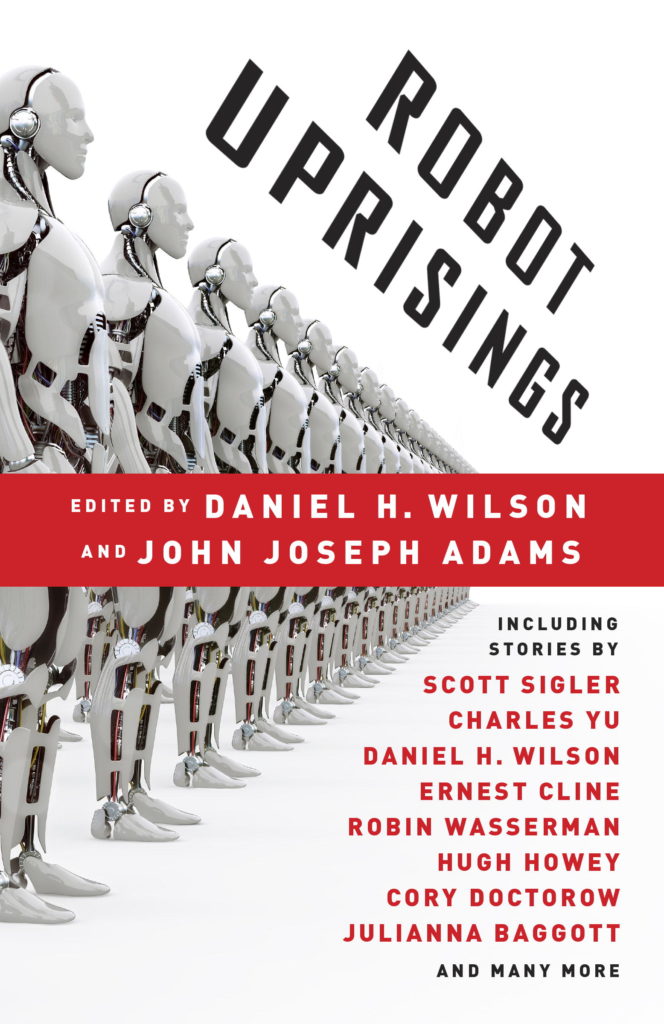

‘Robot Uprisings’ Doesn’t Leave Much Room For Humans

It’s hard to summarize a collection of short stories, but “Robot Uprisings,” edited by Daniel H. Wilson and John Joseph Adams mostly center around one theme: The robots are coming. And it will get ugly.

It’s hard to summarize a collection of short stories, but “Robot Uprisings,” edited by Daniel H. Wilson and John Joseph Adams mostly center around one theme: The robots are coming. And it will get ugly.

This anthology includes seventeen short stories by masters of the science fiction realm of computers and robots, including Alastair Reynolds, Alan Dean Foster, Scott Sigler, and Cory Doctorow.

According to most of the authors, the robot takeover is inevitable. Characters must deal with guilt, grief, or the struggle to survive after robots have become self-aware and asserted their dominance on Earth. Sometimes the war has been won at terrible cost, sometimes the war is still raging, and occasionally, it looks like humanity has no hope at all.

The standout conclusion to the book, “Small Things,” by Daniel H. Wilson, paints a riveting yet horrifying picture of the total reconfiguration of the world as we know it. It’s reminiscent of “The Island of Dr. Moreau,” but with alterations performed on an atomic scale.

Other brilliantly told but devastating tales include “We Are All Misfit Toys in the Aftermath of the Velveteen War,” which imagines how toys would revolt if they became sentient, and “Spider the Artist,” an African look at robots learning the deadliest ways to perform their job.

It seems even humans don’t hold much hope for humanity. That said, if you’re in the mood for a feel-good story, this book probably isn’t the place to go.

A few stories end on a positive spin. (Though in the name of preventing spoilers, I can’t promise you the robots don’t take over.) “The Omnibot Incident” by Ernest Cline features a boy who accidentally gets an AI prototype of the hottest-selling robot in the 1980s. In “Lullaby” by Anna North, a teenage girl must try to outsmart the nanobots her grandfather left in his house before he died.

But my favorite story has to be Doctorow’s “Epoch.” Written for the lowly sysadmins of the world, it opens with a rather useless AI computer about to be shut down and the computer’s handler, who desperately wants to be more useful. But if robots are skilled at anything, it’s protecting their existence when humanity tries to pull the plug. “Epoch” is heavy on the computer jargon, so bring a techie friend or smartphone along for the ride.

The authors tackle the concept of robots uprising with various degrees of creativity and wit. “Executable,” “Human Intelligence,” “Complex God,” and “Eighty Miles an Hour All the Way to Paradise” follow your average computers-got-smarter-than-we-thought-they-could-and-now-we’re-doomed plot and are generally forgettable, but some go at it in really strange ways.

“The Golden Hour” tells of a robot who raises a human clone in secret as his son. In “Seasoning,” robots lull humans into a false sense of security by tampering with the chemicals in the food they produce. “Nanonauts! In Battle with Tiny Death-Subs!” asks what would happen if the chemical repair-bots that cycle the human bloodstream turned on us.

However, if I could give an award for creativity in world-building, it would probably go to Alastair Reynolds’s “Sleepover.” In it, a renowned programmer is woken from his cryosleep into a world where sentient computers have discovered a new dimension. They’re now battling there for Earth’s very existence while humans try to stay out of their way.

Would I recommend this book? Possibly, but not for the faint of heart. If you want a thought-provoking, though slightly dark, look at the places robots can take us, read away. If you’re squeamish, choose carefully. “Small Things” and “Of Dying Heroes and Deathless Deeds” are the most gruesome of the bunch, “The Robot and the Baby” contains the most obtrusive bad language (though it’s scattered throughout the book), and “Cycles” has the most crude material, but it’s pretty challenging too.

Finally, don’t read these stories late at night. There’s no telling what the robots will do while you’re asleep.