‘Hero, Second Class’ Haves At Hackneyed Fantasies

You don’t see a lot of parody in Christian publishing. Or Christian fiction publishing. Or Christian fiction fantasy publishing. Leave it, then, to Marcher Lord Press to find the niche within the niche within the niche, and fill it with style and entertainment: ergo, the first of debut novelist Mitchell Bonds’ comic fantasy series, Hero, Second Class.

Author Mitchell Bonds.

First, a word about the author. I don’t know him. But I’m guessing that for attempting authors, Bonds will likely make you jealous, just because his picture on the back makes him look all of barely-into-high-school. Looks like a fun dude. He also wears a gray hat like Matt Drudge, in that photo; you might almost expect an old-movie-stereotypical little white tag reading PRESS sticking out the top. But of course, it’s the imagination in the comic story-world — it’s derived from fake roleplaying games with his friends, Bonds explains — that makes Hero, Second Class an extraordinarily amusing read.

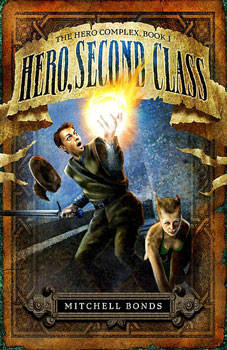

The fun really starts with the presentation. Its cover is comical. The back description makes me chuckle — the same text we have at the book’s page on the Speculative Faith Library. Bonds knows his fantasy conventions well and can spoof/tribute them just as well, especially from popular fantasy, science fiction and space-opera movies. Those familiar with The Princess Bride, Monty Python (I am darn sure he included a Holy Grail copy/tribute) and even the hilarious cartoon superhero spoof The Tick will note some similarities. But he makes the comic style his own — in fact, sometimes to the point of not being sure what he exactly he is trying to spoof. Almost everything is up for grabs.

Yet for fantasy book conventions, the jokes seemed less prevalent. For example, I was sorely disappointed to find no jokes embedded in the requisite Fantasy World Map. That is a convention of fantasy-world books that is just crying out for parody. Maybe someone else has already done that. But you’d have my louder applause of you gave me a fantasy-world map that carries bizarrely unpronounceable names and descriptions of its population — such as a land made up entirely of Forlorn Underdog Orphans who turn out to be Long-Lost Children of Royalty about whom are made Mystical Prophecies.

Yet for fantasy book conventions, the jokes seemed less prevalent. For example, I was sorely disappointed to find no jokes embedded in the requisite Fantasy World Map. That is a convention of fantasy-world books that is just crying out for parody. Maybe someone else has already done that. But you’d have my louder applause of you gave me a fantasy-world map that carries bizarrely unpronounceable names and descriptions of its population — such as a land made up entirely of Forlorn Underdog Orphans who turn out to be Long-Lost Children of Royalty about whom are made Mystical Prophecies.

But even without that, the book is already applaud-able. Even the bad jokes are so bad, they’re good. (“Destiny has decreed …” Groan/grin …) Bonds knows how to hit that sweet spot: he can crack wise with cleverness, or cliches, but either way with hilarity.

Here I must include my favorite part. This is from page 559:

Clad in full Villain gear, including black shirt and rose-red cape, stood Lydia Weatherblade — formerly the White Tiger. She stepped inside the tent. Her armor was an oddity. Though she wore normal greaves, no metal protected her torso, save for a shaped piece of metal across her bosom.

[Cutaway to an author explanation paragraph, prevalent throughout the story.]

Originating in the Eastern Islands, the Breastsplate is a singularly useless piece of armor. Indeed, it is good for nothing more than putting a female warrior’s décolletage on display. Despite its impracticality, it remains popular among Villains for its fashionable appearance and usefulness in distracting male Heroes.

This alone has convinced me to recommend HSC, and forever refer to ridiculous female “armor” on the front of pulp fantasy book covers, video games, etc., with that name.

By the way, for parents and leaders: that’s as edgy as the content gets. Bonds knows how to pull back from the tricky parts, even involving a (slight spoiler) love story between a human young man and a young cat-woman. His intentional pull-away from an intimate scene, for example, winks not at something prurient, but at those authors who do so wink.

At first, I spent time looking for any Overt Christian Messages to kick in. They arrived later in the story: standard fantasy allegory, really, with one Creator and an eternal plan somewhere above all the wackiness. But they almost seemed — to this lover of organic overt messages — to be foreign additives. Oddly enough in this case, I would not have been bothered if the serious more-direct-Christian stuff wasn’t there, but I can understand the need for it.

As an oft-attempted humorous-fiction writer myself, I could have a few suggestions for punching up the hilarity here and there. (Example: at least one character must be the serious Straight Man in a comedy story. Here I would have recommended the narrator fulfill this role, for I find dry narration of hilarious events even more hilarious.)

But that’s where my critiques must end. For me, it’s far too difficult to kid a kidder.

Hero, Second Class is ultimately an amusing and different read. It’s also blessedly thick.