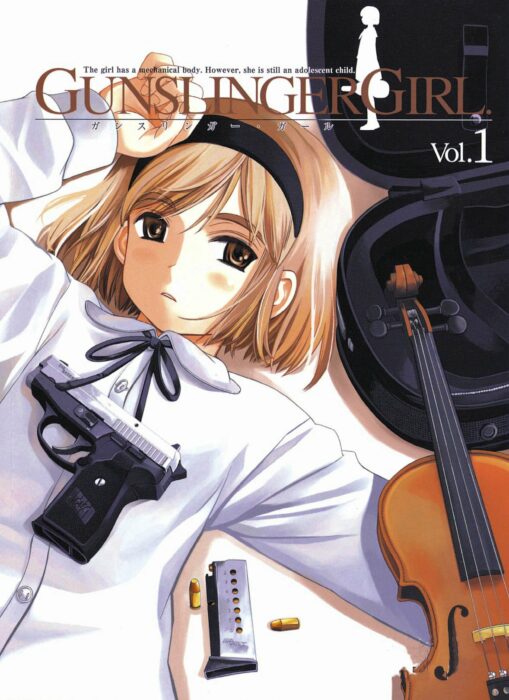

‘Gunslinger Girl’ Shows the Inevitable Tragedy When Man Tries to Play God

Previously I’ve written reviews for anime series, and even a couple of comic book stories, but here’s something different: I’m reviewing the manga series Gunslinger Girl. This may also be the densest story I’ve reviewed, or at least up there with FMA: Brotherhood. That’s because Gunslinger Girl is filled with well-developed characters as well as intriguing moral and ethical difficulties. I hope I can do it justice—apparently unlike the anime series.1

Enter the world of Gunslinger Girl

Italy: a place filled with rich culture, great art, and phenomenal food. It’s also a land of great unrest. Political and economic conflicts aren’t just confined to words and debates. They’re also expressed in violent terrorist attacks.

From the outside, the Social Welfare Agency (SWA) looks like a government charity, designed to help children who had experienced severe mental and physical traumas. On the inside, the SWA is taking many of these children, mostly young girls, and creating soldiers to fight the terrorists. The agency enhances these children’s bodies with cybernetics, and reshapes their minds with a conditioning process involving drugs and hypnotherapy.

For two brothers, Jean and Jose Croce, the SWA offers an avenue toward a more personal goal. Years before, their parents had been targeted and killed in a massive car bombing, an attack that also killed their beloved little sister and Jean’s fiance. They now want to find the man who planned and carried out the attack, and when the do, they intend to use the cyborg soldiers as tools to get their revenge on him.

The name Gunslinger Girl actually doesn’t fit well

Unfortunately, the series’ English name doesn’t work in the series’ favor. It’s a rather cartoonish name for a story that has very few cartoonish elements.

The word “gunslinger” usually connotes the American Old West, where two men face each other on the dusty street of a small town of clapboard buildings, their hands hovering over their holstered six-shooters, while townsfolk hide behind doorways and windows whilst peeking out to see which gunfighter will outdraw the other. It’s awkward to apply that word to this story.

Even the singular word “girl” is not very accurate. Six of the cyborg girls take turns in the story’s main focus, and three of them could be considered the story’s main character. If I understand it right, the Japanese language does not have plural nouns in the same way that English does, so maybe the problem was with someone not understanding the story all that well before they had to come up with a translation of the name.

Who are the good guys in Gunslinger Girl?

It’s easy, and not unjustified, to paint the Social Welfare Agency as bad guys. At least it’s beyond questionable that no one should use children as assassins and murderers. But while the story does critique the SWA, it even more sharply critiques the “real world” through the SWA.

Two of the girls came to SWA after being brutalized and tortured almost to death. Another girl has been paralyzed from birth and abandoned by her family. A fourth girl’s own parents tried to stage an accident so they could collect life insurance money from her death. Only one main character has a more normal backstory. She’s a Russian/Ukrainian girl who is close to fulfilling her dream of becoming a ballet dancer. Then she learns her bone cancer (linked to the events of Chernobyl) means she’ll need to have one of her legs amputated, and tries to take her own life.

Otherwise in the SWA, outside of paramilitary training and killing bad guys, their lives are almost disturbingly normal. One girl grows a garden. Another owns a teddy bear collection. One night they go out to see a meteor shower and end up singing Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

Even most of their handlers try to treat them well. Earlier I mentioned Jose, one of the Croce brothers. For most of the story, he seems to see his cyborg trainee, Henrietta, almost as if she were his little sister, perhaps as a replacement for the sister killed in the car bombing. He takes her stargazing, encourages her interest in photography, and even takes her to a performance of The Nutcracker. When Henrietta is not in take-down-bad-guys mode, he seems to want her to have as normal a life as possible. Yet her real value to him is revealed when the SWA learns information about the man who killed his family, and he must decide whether he wants to go into battle with a reliable weapon or an increasingly unreliable person.

Then there’s Hilshire and Triela. Their story goes back to even before they joined the SWA. They show humanity at its worst and most fallen. Hilshire helped rescue a young girl who began as a victim of child trafficking, and then was nearly murdered in a form of vile and depraved entertainment—but not before she had greatly suffered in mind and body. The SWA saved her life and restored her body with their cybernetics, but at the cost of dragging this girl into their crusade. Hilshire is the one handler most dedicated to his cyborg’s well-being.

Tell, don’t show

In fall 2020, the internet caught fire over the movie Cuties. Some articles explained how the movie set out with a good goal: to explore how our culture exploits young girls. But the movie failed in its message because the film ended up engaging in the same kinds of exploitation it sought to condemn, by exploiting its own child actors.

Gunslinger Girl looks at some very dark corners of humanity, but we can learn from how this story looks into these corners. As a manga, the story is told in visual format, but artist Yu Aida still doesn’t try to shock us with explicit details. For example, when Hilshire—as a Europol officer before he joins the SWA—wants to hunt down people involved in child trafficking, he is shown exactly what terrible things happen to these children and what he may encounter. The reader, however, is only told what he sees, and that is quite disturbing enough.

Aida usually shows just enough hints of evil, and does not revel or even wallow in the details like some shock-fest horror movie.

Gunslinger Girl’s tragic ending

Early on, Gunslinger Girl implies to readers that this story will not end well for the main characters. Perhaps it’s the references to Italian tragic opera, or the story’s jarring combination of childhood innocence with ruthless violence. Maybe readers just know that man cannot play God with people like this, reprogramming their minds and removing their memories, without such experiments coming back to harm them. At the risk of spoilers, that’s largely how Gunslinger Girl plays out, either loudly and discordantly, or with quieter and bittersweet tones.

We could explore more about Gunslinger Girl, such as the gut-wrenching storyline involving the Prince of Pasta. I could describe Pinocchio, who provides a kind of mirror image or photo negative of the cyborgs. We might find noteworthy the fact that an action/drama story set in Italy doesn’t focus much on that country’s two most famous (or infamous) institutions: the Catholic Church and the Mafia.

This is not a light, fun read, as is typical in some comic or manga fare. Instead, Gunslinger Girl shows that this graphic story form is capable of far more than another round of caped heroes bashing dastardly villains. This medium can add a pinch of sci-fi and give us a story that may rival classical literature by looking at the good and the bad in humanity. It’s not an easy read, but it’s a good read.

- You can find two anime series for Gunslinger Girl. The first anime series introduced me to the story. It was good, but it felt incomplete, as if the story was barely getting started by the time the last episode ended. The second series, Il Teatrino, was produced by a different animation company. I haven’t yet watched it. ↩

I only watched the first anime. Everybody in the second season looked constantly off-model and I couldn’t put up with it for more than, like, 5 minutes.

But basically the TL;DR version is that this is the pre-Violet Evergarden version of Violet Evergarden.

Also I would argue that the themes would be more about human nature than about playing God. But I have no bandwidth for that serious stuff anymore. I’m rewatching/rereading the comedy Sleepy Princess in the Demon Castle and it’s currently translated 13 volumes of manga.

I feel a bit dense for not having seen the similarities with Violet Evergarden. Oh, well.