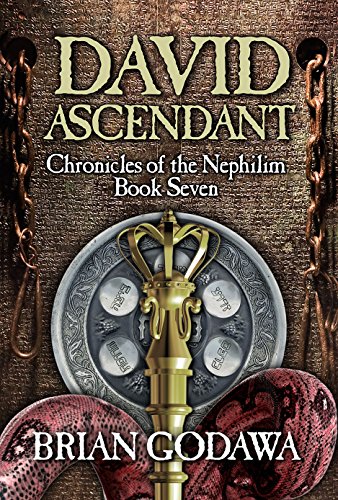

‘David Ascendant’ Faces Giant Flaws and Thrills

Only three years separate the publication of Enoch Primordial — chronologically the first novel and publication-wise the second in Brian Godawa’s Chronicles of the Nephilim series — from that of David Ascendant, the latest installment, but those years have wrought a notable improvement in both the structure and style of Godawa’s storytelling. SpecFaith readers may remember my harsh review of the former novel several months ago, and thus it is with a measure of relief that I may now report, with significant caveats, that things appear to have changed for the better in Godawa’s ongoing “Biblical Cosmic War of the Seed.”

The first such improvement manifests in characterization. While the heroes and villains of Enoch struck me as one-dimensional plot-slaves, those of David Ascendant are — as a general rule — well-motivated, empathetic, and often at odds with their apparent destinies. This level of nuance is immediately apparent in Godawa’s bold decision to begin the narrative from the perspective of the Philistines, thereby introducing his Israelite protagonists through a lens which views them as brutal, unsophisticated barbarians. The default narrator bias found throughout Enoch is here notably absent. Though the novel follows the ascent of King David of Israel — the “man after God’s own heart” — rarely does it ensconce its titular hero on a pedestal of any kind. If ever David’s faults aren’t apparent to his own eyes or those of his fellows, they certainly won’t escape the notice of those enemies made to suffer by his successes. Through straightforward point-of-view storytelling, the reader is forced to relate to pagans dedicated not only to the destruction of God’s chosen people, but to the desecration of His created order. I found this a refreshing approach.

Not so refreshing, of course, was what I was forced to relate to. David Ascendant is not for the faint of heart. The story opens with a violent act of sodomy and doesn’t let up from there. In terms of content, the novel reads like a Christianized Game of Thrones: explicit nudity, pervasive sexuality, graphic gore, and strong language are found throughout. If the intent of all this visceral, passionate depravity was to de-sanitize a narrative all-too-often bowdlerized on the altar of Family Values, then it certainly achieved that objective in my mind. Indeed, during the blood-soaked second act it became difficult for me to keep slogging onward. I know every reader has a different emotional threshold for such things, but I just want people to be aware of what they’re getting into if they decide to enter this story-world.

As a series, The Chronicles of the Nephilim inhabits the genre of “secret history”: it purports to read between the lines of scripture in order to relate to us what was really happening behind the scenes in Israel ten centuries prior to Christ. According to David Ascendant, the greatest challenge faced by the second king of Israel and Judah was that posed by the remnant of the Nephilim — giant offspring of humans and fallen angels. No Sunday School tale this: here there be demigods and literal cat-women and glowing Urim and Thummim. (The fact that Brian Godawa appears to actually believe his secret history — holding court in an appendix peppered with the phrase “though it is not stated explicitly” in order to explain the purported plausibility of his version of events — is a discussion for another day.) It may be unrecognizable, but, as an exercise in revisionist history, David Ascendant is masterful. Godawa manages to impute new motives to old heroes and villains with an ease that belies its intricacy. If you haven’t read the books of Samuel, Kings, or Chronicles recently, you may find yourself struggling to perceive the seams between fiction and reality.

Second on the list of intra-series improvements is the structure of the plot itself. Whether due to a matured sense of pacing or a relative wealth of source-material, Godawa’s Saul and David, unlike his Enoch and Methuselah, rarely lapse into pedestrian predictability. Instead they behave — as I’ve mentioned — like real people. Thus it is that, rather than functioning as a predetermined paradigm for action, the plot seems to flow directly from the decisions, the mistakes, and the triumphs of those involved.

Here, Godawa has his finger on the pulse of his characters. It’s the little things — things like Ittai pouring himself a drink to settle his nerves after a genuinely tense confrontation, or Joab’s laughter after he pranks a suspicious sentry, or Saul’s heavy breathing as an evil spirit tempts him in the darkness of his chambers. These people feel real, moment-to-moment, because they react to their circumstances in relatable, well-motivated ways. Unlike the plot-driven railroad that was Enoch, this story provides the members of its cast the room to breathe, to doubt, to wrestle with the implications of their and others’ actions. Instead of accepting the world at face value, these people question their own motives and those of their neighbors, thus imbuing a story that might otherwise have been stale with a sense of present-tense dynamism. And all this is achieved without sacrificing the appropriately-epic loose-end tie-party at the climax. Very nice.

What allows for this kind of realism is the absence of narrator bias. Unfortunately, opinions from on high do eventually start reappearing. During the second and third acts especially, moments of genuine terror or disgust are diminished by the author’s compulsion to comment thereon. For instance, when a Philistine army uses Israelite captives as human shields in a thinly-veiled reference to the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the narrator’s superfluous description of the tactic as “a barbaric act of unusual cruelty” does nothing but distract from what could’ve been authentic, unprompted horror in the mind of the reader. Instead of allowing us to simply reflect on the fact that the Israelite archers feel guilt-pangs when they realize they’ve mown down ranks of their own, Godawa feels the need to remind us that “of course, [the Israelites] did not kill them, the Philistines killed them by using them as shields.” Authentic emotion = gone. Now I just feel preached at.

In any fantasy involving giants, a sense of relative scale is essential. There’s a lot of fighting in this book, and, while the Nephilim-vs-human action isn’t comparable to that of, say, Peretti’s Tombs of Anak, it is taut, dramatic, and approachable. No vague twirling and spinning here; when giants must be confronted by those half their size, the battles unfold in a manner that makes physiological sense and can be followed with the mind’s eye. I’d even go so far as to describe certain scenes — such as a particularly vivid dungeon escape featuring a lot of weapon-swapping and chains ripped from walls — as “cinematic,” an overused adjective if ever there was one.

But despite the novel’s successes in blocking, plotting, and characterization, chronic problems do persist. As the book lengthens, Godawa’s prose lapses into verbosity. Adjectives proliferate unchecked, routinely stacking up two or even three layers deep. “Gibborim” [lit. “mighty warrior”] is always accompanied by “warrior.” Beauty is always “radiant” or “stunning,” strength always “mighty” or “muscular.” This is a book in which phrases like “love’s amorous desire” and “luscious pulpy lips” are allowed to exist unironically. Here, superlatives are commonplace, redundant exposition omnipresent, and descriptive reiteration ubiquitous. It’s dense for all the wrong reasons.

And while the verbiage may labor beneath its own weight, at least the romance through which it must slog is never more than ankle-deep. Ugh; sorry about that, gang. But really bad similes aside, there’s about as much sexual chemistry in this book as in a seventh-grade class discussion of the periodic table.

Alright; I lied. Now I’m gonna stop.

Seriously, though. Every single main character — from Ba’al to Michel to David himself — is sexually ravenous. Sex is literally the only level at which they relate. The men are rapacious; the women nymphomaniacal. I gave up counting the instances in which people meeting for the very first time start fantasizing about bedding each other. When young David first arrives at Saul’s palace in the hope his musicianship may soothe the king’s fits, Saul’s daughters “swoon” over the commoner nobody. They are “entranced by the young man’s handsomeness,” feel a “throbbing desire for the young lion,” and “[want] to surrender their bodies to the comely virile musician.” I, too, felt something powerful take hold of me in this magic moment, but I believe that particular sensation was known as “dry heaves.”

Even Abigail, David’s second wife, who had endured years of abuse at the hands of her pig of a first husband, is won over to ecstasy by Mr. Bond, James Bo— … er, David the Psalmist after only a few hours’ worth of wooing on her wedding night. It’s as though David, and pretty much the rest of the cast, walk around in a cloud of pheromones — as though this entire tale is some kind of ancient near-east Axe deodorant ad. Sex is easy when women think like men. Of course, Abigail later finds out about David’s first wife Michel, and about his third wife Ahinoam, and what then ensues is a deliciously frigid scene of something approaching sexual realism. It’s the best female-heavy scene in the book. Sadly, there are no others like it.

But issues aside, and taken as a whole, David Ascendant is one rip-roarin’ roller coaster of sword-and-sandal war and scandal. It’s an outsized ride: giant in flaw and thrill. If you like your blood warm, your women hot, your angels corporeal, and your Old Testament laced with fantastical flourishes, this may be the book for you.

The account of David certainly gives a reteller more to work with and a better sense of narrative structure than Enoch does. And this reteller certainly isn’t the first one who tried to sound archaically epic and missed (at least I’m guessing “epic” in the Homerian sense is what he was aiming for).

And “pulpy” is the grossest descriptor of lips I have ever seen. “Luscious” is bad enough, being cliched crap, but pulpy is so viscerally as well as intellectually repulsive. I don’t even understand how he arrived at that word; “pulp” has such a gross mouth-feel.

What can I say? It’s biblical pulp fiction.