Retelling Biblical Stories For A Modern Audience, Part 1

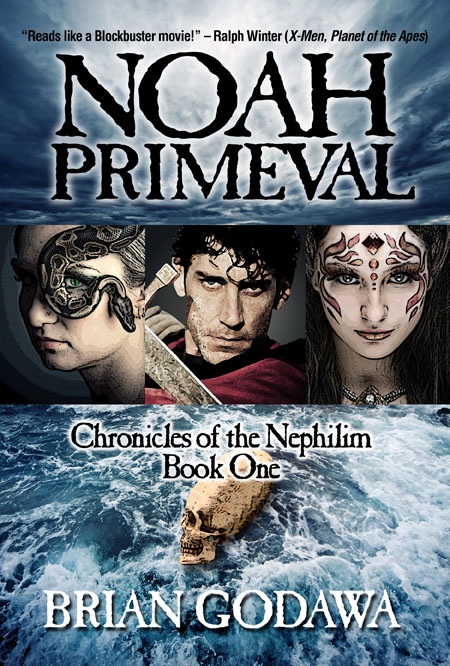

In my new novel, Noah Primeval, Book One of the Chronicles of the Nephilim, I retell the story of the Biblical Noah as a nomadic tribal warrior. He refuses to worship the divine council of gods in Mesopotamia and is subsequently hunted down by assassin giants, leading the chase through Sheol, and ending in a climactic battle involving Leviathan and other hybrid monsters.

In my new novel, Noah Primeval, Book One of the Chronicles of the Nephilim, I retell the story of the Biblical Noah as a nomadic tribal warrior. He refuses to worship the divine council of gods in Mesopotamia and is subsequently hunted down by assassin giants, leading the chase through Sheol, and ending in a climactic battle involving Leviathan and other hybrid monsters.

“What?” you may say. That’s not in the Bible! That sounds more like the non-canonical book of Enoch or the fantasy world of The Lord of the Rings than Holy Scripture. Isn’t that mythologizing the Bible?

It is hard enough to get some religious believers to appreciate the imagination of the fantasy genre. But when it comes to retelling a story from the Bible, their view is categorical: don’t even think of putting those two things together — Bible and fantasy. That borders on tampering with the Word of God worthy of the curse in Revelation 21 on those who “add or take away from the words of the book.”

I think this negative impulse comes from an essentially good intent: the desire to avoid denigrating their sacred stories or reducing them to the level of false pagan myths. But such good intent does not necessarily produce the good result of a well thought out Biblical understanding of story. 1

What would surprise many of these concerned believers is the fact that the same ancient Hebrews who championed the Scriptures as their sacred text containing the very words of God, were also the ones who wrote those Scriptures utilizing pagan imagination and motifs. And they were also the same ancient believers who wrote many other non-canonical texts that retold Biblical stories with fantastic embellishments worthy of mythopoeic masters.

Subverted Pagan Imagination

I have written elsewhere about the extensive use of Canaanite poetry and imagination by Bible authors to express God’s own imagination. 2 The Bible redeems pagan imagination by using its motifs and baptizing them with altered subversive definitions that support Yahweh, the God of the Jewish Scriptures against Baal, the god of Canaan, and other pagan deities in the ancient Near East.

Two examples of this redemptive subversion that show up in Noah Primeval are Leviathan and the Divine Council of the Sons of God. It appears that Yahweh was not only interested in dispossessing the Canaanite people from the Promised Land, he was interested in dispossessing their narrative, because the Bible embodies a subversion of Canaanite imagination within its own narrative.

Baal, the storm god, was the chief deity of the land of Canaan in the time of the Israelite conquest. Canaanite myths depict Baal as a “cloud rider” who defeats the River and the Sea, as well as the Sea Dragon called “Leviathan,” (a symbol of chaos) in order to claim his eternal dominion. 3

In polemical response to this mythology, the Biblical writers describe Yahweh as a “cloud rider” (Is. 19:1; Ps. 104:3-4), who defeats the River and Sea (Hab. 3:8), as well as the Sea Dragon, “Leviathan,” (Is. 89:6-12) in order to establish his eternal dominion (Ps. 89:19-29). It appears that Yahweh, in consort with the human authors of the Bible, is subversively using the pagan cultural motifs and thought-forms of the day to say, “Baal is not God, Yahweh is God.”

In Psalm 74, 89, Isaiah 27, and Isaiah 51 the story of the Exodus crossing of the Red Sea is described with the imaginative terms of creating the heavens and earth, crushing the head of Leviathan, and binding the chaos waters of the sea in order to establish Yahweh’s covenantal dominion on the earth in his people. This is history mixed in with mythopoetic imagination to describe the theological significance of what is taking place – just like other ancient Near Eastern religions did. 4

Another aspect of Canaanite pagan mythology that is redeemed in the Scriptures is the Divine Council of the Sons of God. In the sacred Baal texts we read about the “Sons of God” who act as an advisory council and judicial board to a Father deity called “El.” Baal is a vice regent who ascends to the throne of El and rules over the other gods of the council, who then do his bidding. 5

In the Bible, Yahweh (also called “El”) presides over a divine council of the “Sons of God”, (Ps. 89:5-7) who also give advice in judicial decisions of Yahweh (Ps. 82), and carry out his bidding as well (Job 1:6-12; 1 Kings 22:19-22). A deified figure called the Son of Man is a vice regent who ascends to God’s throne surrounded by those “holy ones” who do his bidding (Dan. 7:9-14).

Of course, there are significant differences that separate the monotheistic Biblical divine council and the polytheistic pagan Canaanite divine council. As one example illustrates, the Biblical divine council are not to be worshiped, but Yahweh alone; while the Canaanite divine council were worshiped. Big similarities, but bigger differences. Biblical imagination is not engaging in syncretism (blending opposing views), but in subversion (infiltrating and overthrowing an opposing view). The commonalities show a clear cultural connection that is subversively redeemed and redefined in the Biblical understanding of the concept. God incorporates pagan imagination and motifs into his own narrative and subverts them through redefinition and poetic usage.

So that’s what I did in Noah Primeval. I retold the story of Noah, utilizing mythopoeic notions of Leviathan as a personification of chaos, and the sons of God as the divine council around God, as well as the incorporation of other Mesopotamian imagery in order to give a theological explanation for the true origins and partial reality of pagan mythology.

Don’t worry, it’s not as head trippy as all this academicspeak may sound. This is just the deep stuff behind the exciting fantasy action adventure in the novel. But there are appendixes in the book for those who want to explore the Biblical and ANE research more in depth.

1 The curse of Revelation 21, is not a reference to the entire Bible, but the prophecy of the particular book of Revelation. Also, the context is not about taking away individual words but about taking away or adding to the content of the prophecy. If it were words, then we are all condemned because we do not have the original words, but only English translations based on many different copied manuscripts with lots of different textual variations. In other words our book of Revelation contains added words and taken away words.

2 See Wyatt, N. Religious Texts from Ugarit. 2nd ed. Biblical seminar, 53. (London; New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002). Also, Brian Godawa, “Old Testament Storytelling Apologetics,” at www.godawa.com.

3 See my article “Biblical Creation and Storytelling: Cosmogony, Combat and Covenant” for a detailed explanation of this ANE technique.

4 See Michael S. Heiser, The Divine Council In Late Canonical And Non-Canonical Second Temple Jewish Literature (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2004) 34-41; Patrick D. Miller, “Cosmology And World Order In The Old Testament The Divine Council As Cosmic-Political Symbol” Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays by Patrick D. Miller, (NY: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000).

5 For more differences explained, see Gerald Cooke, “The Sons of (the) God(s),” Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, n.s.:35:1 (1964), p 45-46.

– – – – –

Brian Godawa is the author of the new Biblical fantasy novel, Noah Primeval, now available for purchase on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To see a trailer, read an author interview, sign up for free chapters, and learn more information about the Chronicles of the Nephilim, visit the Noah Primeval web site.

Brian Godawa is the author of the new Biblical fantasy novel, Noah Primeval, now available for purchase on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To see a trailer, read an author interview, sign up for free chapters, and learn more information about the Chronicles of the Nephilim, visit the Noah Primeval web site.

Mr. Godawa is also the award-winning screenwriter of the feature film To End All Wars, starring Kiefer Sutherland. In addition, he authored the popular book Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment (IVP). Visit his web site for films and other books and free articles.

Brian, this is brilliant, and thank you so much for exploring this topic.

It’s something I’ve been meaning to look into for a while, to show how fearless God is — and His people have been — in not only avoiding false religions personally, but flagrantly subverting them. “Redeeming myth” is not original with the Inklings. Scripture itself does this (but, oddly enough, we hear little about the Inklings basing their arguments in Scripture itself, that myths can be co-opted by the “true myth”).

Other examples: Daniel in Babylon (Daniel 1), and Paul in Athens (Acts 17).

I’m curious also about something another one of our contributors (who wrote this) once mentioned about Jewish literature. What did the Israelites think about not only different forms of art meant as praise to God (such as the Psalms), but storytelling?

Moreover, how can those who love visionary stories for God’s glory apply the fact that Scripture, while certainly blasting acceptance of paganism, subverts paganism also?

One suggestion: we can find examples of what God is like even in modern-day stories.

What do you love so much about Gandalf? God, Who is real, and truly like that.

Do you pine for the wonder of the world of Harry Potter? That kind of magic isn’t real, but God is the only true source of such wonder and miracles, goodness and friendship.

Stuck on Twilight? It has some issues. But true love can only be found in your Savior.

Those are just a few thoughts. I look forward to other reactions from others. Thanks to your work and others, whew, we’ve really had a boom week on SF. Soli Deo gloria.

Thanks, Stephen.

Curtis Chang wrote a book about how Augustine and Aquinas subverted their pagan culture, but he didn’t write about how the Bible does it. So I did in my book Word Pictures. Also you can read the free article I wrote on Acts 17 and Paul subverting the Stoic narrative here: http://godawa.com/Writing/Articles_And_Essays.html.

The next post will explain how 2nd Temple Jewish literature retells Bible stories with fantastic imagination. It was one of their techniques.

I believe the ability of God’s people to use pagan notions without accepting them lies in the redefinition that occurs with subversion versus the adoption that occurs with syncretism.

I like your thoughtful questions. All truth is God’s truth — in context.

Where has this article been all my life? Going to read it in a moment …

But not before asking this: have you noticed even the solid-theology Christians neglecting the Acts 17 incident, and Paul’s thought process, mainly because others seem to have abused it? (E.g.: Well, Paul quoted a pagan poem, so that means I must play a pagan secular song in church! And anyone who disagrees is a legalist, so nyah-nyah-nyah.) So based on such ill-motivated citations, other Christians say they want to have nothing to do with how Paul reached some of the pagan Greeks.

Your thoughts? After I’ve sneaked in some of my own, that is? 🙂

Now I even more highly anticipate this. God is indeed in the business of redemption, and without lapsing into universalistic definitions of redemption outside the Bible’s parameters, it’s amazing how much His quest of redemption truly encompasses.

Or, to co-opt the words of a modern “pagan” “poem”:

Just a note: Though I think the curse of Revelation 22 was in fact intended to say “No more Bible. The end,” I’d also argue that the great big “FICTION” label on works such as yours should render any such debate irrelevant. If the Book of Mormon were treated as fiction, I wouldn’t have a problem with it. It’s only when we start calling a thing “canon” that we can start talking curses – and heresy.

Christian myth is a lost art. Aren’t we old enough to separate fact from fiction?

Not if we keep encouraging each other in Christendom that fiction inevitably cause, at worst, lost faith, and at best, wrongful obsessions. 😉 But, that’s one of my little pet peeves (and certainly not the only existing issue). Another related peeve is the recurrence of outsourced discernment to professing “media shamans.” You don’t need to be exposed to this bad stuff. I’ll do it for you! ‘Cause I’m the more-spiritual one. Every Christian, in some way, believes that some Christians are “powerful” enough to take it on the chin for Discernment. They just don’t apply it consistently.

I do believe fiction is powerful, as powerful as a weapon, and can be wielded thusly even with a clear label: This is Just Fiction. Similarly, nasty songs can still get stuck in our heads and affect our thoughts. But when compared with worship of Christ and seeking the Spirit’s increasing holiness in our lives, even bad (as in, faith-bad) fiction is not powerful enough to overwhelm us — not without our willing consent.

Andrea,

What can I say, but “amen”?

Love it. Brian, as usual, has some great things to say about subverting pagan worldviews in our fiction. However, my single, broad caveat is his approach to the relationship between pagan narratives and Scripture. It is by no means a demonstrated fact that the Bible takes pagan narratives at all; it is in fact a hotly contested assertion. In fact, in my view, it approaches things from precisely the wrong end.

God created the world; God built the monomyth into our hearts and minds. The pagans then created their own corrupted myths using the same structure. The Scriptures aren’t written to subvert these pagan myths – they’re written to illustrate the true story. Genesis, for instance, isn’t written in response to some Canaanite myth somewhere, but is rather written the way it is written because that’s how it happened. Any similarity comes from the pagan peoples ’round about stealing narrative structures from God. The chief difference being that in one view God is on the defensive, trying to correct pagan myths that came first, while in the other the Scriptures stand as God’s testimony to the truth which the pagans have corrupted. Perhaps the pagans wrote their myths down first, but who was around first, God or fallen man?

Adam,

I agree with you in principle. That is, pagan mythology is a distortion of the embedded truth of God. As for which way the influence flows, we cannot deny that Moses and the other authors used human sources and were educated within their human culture that affected their imagination. They did not received automatic writing directly from God. The doctrine of Inspiration affirms the human part of the equation.

So I guess you might say not that Paul was returning the Stoics to the original myth, but that he was subverting their mythology that subverted God’s original truth. But Paul DID follow the Stoic narrative and not necessarily the Old Testament narrative, which was one of Creation, Calling, Exodus, Exile, and Return. Of course, he identified with what was TRUE of that Stoic myth and then twisted back with an antithesis of the Gospel story of Resurrection and Judgment.

The Gospel is ultimately a story and that story is very flexible in terms of finding points of contact because it’s elements are reflected unwillingly or willingly in all stories to some degree.

Adam, your perspective is right, putting history before myth. ‘Right’ is something I rarely say in discussions like this. Sorry, Brian, Stephen, and others! I can’t argue my case, but Adam has.

Just reading along and enjoying the discussion right now. 0=) Brian, have you used the Chronological Study Bible at all? It draws some fascinating literary parallels between the narratives.

Hi Kaci,

No, I have not. Is it online?

Hey, Brian,

I don’t think there’s an online version yet; wish there was at least an e-reader copy to direct you to.

Interesting discussion,

Galadriel, glad you were here. Some glitch? Come back! You probably have…

Very interesting discussion indeed. As a believer, I am drawn to the bible first and foremost and it has all the elements to carry with me in life: History, poetry, parables, letters, and prophecy.

I am also a student of literature in general and enjoy Greek Mythology- not sure sure if the two entwine at all. But I like to write stories which incorporate belief in God and those gray areas I don’t understand. I also love Christian Philosphy, apologetics, and any book about defending my faith. I think it makes my faith stronger and helps when I write as well.

Thanks Brian for introducing us to these concepts. I can’t wait to read Primeval!

Erica

I too want to read Noah Primeval, as fiction like others do. In my fantasy realm, fairies of human-like stature live. One of the characters theorizes that they’re the offspring of fallen angels and women. Some of them are among the elect. When born from above, their powers and enchantments, and glorious wings, are lost to them, and replaced by godly joy. It’s one thing to write such fiction, another to speak about the Biblical histories as intentionally authored to subvert pagan myths.

A book that is relevant to what you are writing here is The Bible Among the Myths by Dr. John Oswalt. He also mentions the use of “leviathan” (chaos monster) borrowed from Canaanite literature. The Hebrews would have known that the Bible writers were referring to with this reference and not what some modern readers like to read into it. Through modern eyes all sorts of animals including dinosaurs are claimed. The cultural context would suggest otherwise. It sounds like you have created a fascinating story using such things as a jumping off point.

I’m usually one to steer clear of biblical fiction, simply because much of it is poorly-written, dull or too safe, in that the author is restricted from telling a good story. Another reason is that some authors stay so close to the Bible and say nothing new (or interesting) so the reader feels like they could just read the Bible instead (not that that’s necessarily a bad thing! – reading more of God’s Word). That said, I’ve read several books that were good. One such example is Havah: The Story of Eve by Tosca Lee. Noah Primeval sounds like a good read. I may have to check it out.

Galadriel, some of your comments on these blogs seem like spam eg. ‘interesting discussion’. They don’t add or say anything. If you don’t have anything to say, there’s no need to comment.

Jonathan Rogers’ “The Wilderking” trilogy is also really good. Short books, quick reads, and reminds me a bit of Mark Twain-meet-CS Lewis.

Brian, I plan to read your book, and have gotten a friend to think about reading it! Your theories are more difficult for me. I hope that’s okay.

Maria

[…] Maria Tatham: Brian, I plan to read your book, and have gotten a friend to think about… 8:05 pm, November 16, 2011 […]