Redeeming Zombies

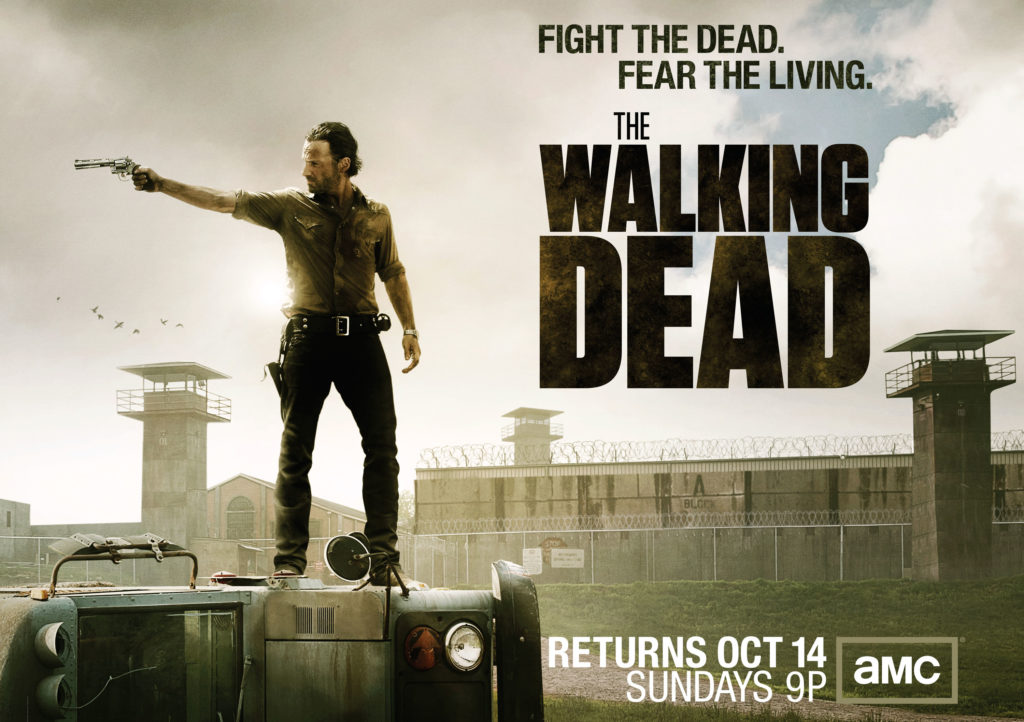

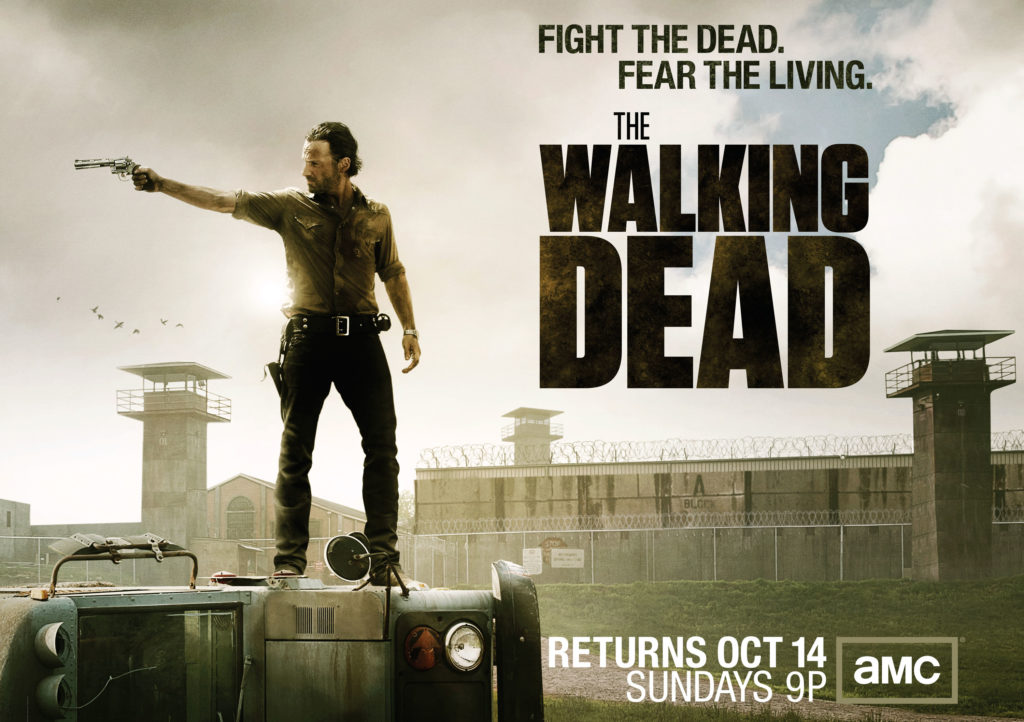

The Walking Dead is back for a fourth season and zombies have never been more popular. Ratings for AMC’s acclaimed series has multiplied every season thus far, and shows little sign of abating any time soon. The summer’s Brad Pitt-fueled, sanitized zombie-thriller World War Z was nothing but throwing gasoline on a flame; due to its PG-13 rating and minimal violence it opened the zombie craze to even more people who would have been put off by the grueling violence common to the genre. There are plans for two more follow-ups to World War Z. The hipster rom-zom-com Warm Bodies, along with popular satires like Zombieland and Shaun of the Dead, have breathed new life to the genre over the last decade, proving that there is yet life in the stories of the undead.

The Walking Dead is back for a fourth season and zombies have never been more popular. Ratings for AMC’s acclaimed series has multiplied every season thus far, and shows little sign of abating any time soon. The summer’s Brad Pitt-fueled, sanitized zombie-thriller World War Z was nothing but throwing gasoline on a flame; due to its PG-13 rating and minimal violence it opened the zombie craze to even more people who would have been put off by the grueling violence common to the genre. There are plans for two more follow-ups to World War Z. The hipster rom-zom-com Warm Bodies, along with popular satires like Zombieland and Shaun of the Dead, have breathed new life to the genre over the last decade, proving that there is yet life in the stories of the undead.

All of this then begs the question: What are Christians to do with zombies? The most common responses I have seen have been either opposition or public silence coupled with private tolerance and enjoyment. Christians who oppose the genre do so for the same reasons evangelicals seem to object to everything: too much violence, too much nasty stuff. Christians who stay publicly silent leave those with questions or concerns to their own devices. If we really believe everything has theological implications and that the Bible addresses all areas of life, we should not shy away from exploring various Christian approaches to zombie-lit, so long as we do so with gentleness, care, intelligence, and wisdom.

A common approach I’ve seen and witnessed in personal conversation (an approach which sparked this article) is to oppose zombie fiction and films because it presents a sort of anti-Resurrection theology which proponents claim “sully” Christ’s own Resurrection and trivializes death, which is supposed to be our enemy. Such a position creates an unnecessary opposition between Christianity and this popular genre, and is more likely to lose the only opportunity which such a Christian will have to speak into the life of those many young people who are crazy for zombies.

Such opposition is unnecessary because it insists on perfect theological accuracy from pop culture. Granted that we want to be clear in our doctrines in the real world, and granted too that just about every genre and style of story produced by man reflects God’s truth on some level, but this is often confused for requiring cultural artifacts to communicate rigorous doctrinal constructions perfectly and without error. Our best theologians and systematic theologies can’t even do that, much less an unbeliever. Neither C. S. Lewis or J. R. R. Tolkien thought this way either. In the preface to his The Great Divorce, Lewis was quite clear that his medieval dream-vision was not to be confused with reality: “I beg readers to remember that this is a fantasy. It has of course—or I intended it to have—a moral. But the transmortal conditions are solely an imaginative supposal: the are not even a guess or a speculation at what may actually await us.” All speculative fiction is the same, an “imaginative supposal,” a “what if,” and we do ourselves nor those we intend to help any favors by treating them as depictions of reality and then comparing them to how Scripture delineates that reality.

A proper approach to zombies must begin with the origins of the metaphor, or symbol. There were not, after all, zombie stories in the tenth century. As with the rest of the “horror” genre, zombies developed in the early decades of the twentieth century. There had certainly been folklore about the voodoo religion and mindless walkers, but there is some debate about whether such people were actually dead or simply unconscious. In either case, the cause of their “zombie-ism” was magical, not scientific. The origin of the modern zombie came about in the first decade of the twentieth century as an expression of modern unease toward modernism and globalism, the industrial revolution, and the mass movements of the developing nationalism that would later burgeon into the massive conflicts of world war.

Zombies, thus, are a symbolic expression of the hidden dark side of the modern world and many of the maladies that Christians are also concerned about. They are a parody of human relationship and human life, where proximity toward others is a danger instead of a good, where mass movements and “trends” have the effect of spreading by way of touch and “word of mouth,” a process which subsumes the flourishing of human life with its variation, diversity, and hierarchies of loves and passions and personalities into a monolithic mass of undifferentiated and unconnected hyper-individuals. This has been the standard definition of a “mass movement” in contrast to a true community. A mass movement unifies by means of an abstract ideology to which each individual adheres, the abolition of the individual personality which reduces human relationships to the unconnected individual and the governmental or economic structure. A mass movement, then, has the effect of destroying true community, which includes a loyalty to actual persons rather than to ideas and ideologies, and where genuine discussion and disagreement can occur without expulsion or a crisis of identity.

Zombies, thus, are a symbolic expression of the hidden dark side of the modern world and many of the maladies that Christians are also concerned about. They are a parody of human relationship and human life, where proximity toward others is a danger instead of a good, where mass movements and “trends” have the effect of spreading by way of touch and “word of mouth,” a process which subsumes the flourishing of human life with its variation, diversity, and hierarchies of loves and passions and personalities into a monolithic mass of undifferentiated and unconnected hyper-individuals. This has been the standard definition of a “mass movement” in contrast to a true community. A mass movement unifies by means of an abstract ideology to which each individual adheres, the abolition of the individual personality which reduces human relationships to the unconnected individual and the governmental or economic structure. A mass movement, then, has the effect of destroying true community, which includes a loyalty to actual persons rather than to ideas and ideologies, and where genuine discussion and disagreement can occur without expulsion or a crisis of identity.

Zombie-lit, as an expression of this destruction of true community, can then be seen as a dark side of our consumer culture. We are all commonly referred to as “consumers” and participate in a globalized system of “consumption” of the goods produced by our world-wide manufacture of goods. The potential for such a system to enslave and overshadow all other relationships in human life is well documented, and zombies, which symbolize this danger, express this fear. We are “consumers,” but we are also the consumed, we are devoured and ingested by such a system and then pass on our infection to others, spreading the enslavement and destruction of human life. Anyone who has done any research on the effect of unfettered globalism on people in the third world cannot deny the ravenous nature of such a system (I suggest starting with Bales, Disposable People). The cost in human flourishing, human good, and human health has been well-documented.

Engaging young people on the implications of the symbolism of zombies can promote a better understanding of our world, and can even point to the Body of Christ as a refuge against the ravages of a relentless, devouring culture of consumption in which all things are consumed, including, in the end, ourselves.

We can go further than a critique of our cultural moment, of course. Theologically, zombies symbolize man dead in his sins, desperate to infect others. As Proverbs says, sinners love company and seek to corrupt the innocent. The zombie, as an expression of man with nothing left but the base instinct to feed and multiply can represent the “old man” of the flesh with his base desires. This could be a helpful springboard for Church study discussions on sin and the brokenness of man.

I have found one of the most interesting implications of zombie-lit, and The Walking Dead in particular, is what it tells us about our identity as Christians and the application of Christian ethics to various situations. When I started watching The Walking Dead, I watched with a group of other Christian millennials, and the most common discussion point between episodes was how we would have responded to such a hostile world and the situations in which Rick and the others frequently found themselves. The majority of these Christian young people concluded that normal human and Christian ethics were off the table in such a world. In such a post-apocalyptic and Darwinian world of survival of the fittest, they argued, survival is the preeminent necessity, and was therefore the highest virtue. This prompted me to ask whether Jesus’s moral claims were only of limited application, or whether they applied in every situation we found ourselves, no matter how extraordinary. Was there a situation in which Christian ethics did not apply, a crisis that was excepted from the comprehensive claims of Christian identity over our whole lives?

They said Jesus didn’t have a zombie apocalypse in mind when He laid out the Sermon on the Mount. Well, of course not, but He wasn’t thinking about transcontinental air flight either, but that doesn’t mean His claims don’t extend to airlines. And besides, I pointed out, Jesus had shown us how believers are to behave in an actual apocalypse, the type of apocalypse to which a zombie uprising would pale in comparison. Regardless of your views on the book of Revelation, we can agree that it was vision Jesus gave to John for the Church as a guide for how to behave when the world seems to be coming apart. And Jesus valued martyrdom and faithfulness over survival any day of the week. “And they have conquered him by the blood of the lamb and by the word of their testimony, for they loved not their lives even unto death,” (Rev. 12:11).

Above all, this seems to be the most practical and effective use of zombie-lit for us as believers. The opportunity to engage young people on ethical behavior and the radical call to obedience to God in all circumstances cannot be tossed away, especially with all of the competing loyalties and conflicting accounts of what is good and just in this world. Let us not turn away from this opportunity neither with pietistic dismissal and opposition nor with silent toleration.

Thanks for the reminder that I don’t have to fear things in the culture, but that I can use them to talk with my kids about Jesus.

I thought Warm Bodies was particularly good regarding the explanation of how zombieism started (the book even more so than the movie). After years of having their relationships overshadowed by their electronic devices, people just sort of deadened, mentally and socially and finally physically. The undead craved the interaction and experiences they used to have and tried to relive them without being fully aware of what they were doing or what they were missing.

Brandi, I agree. I enjoyed both book and film, and unlike a lot of zombie stories, it actually holds out hope for their redemption. Looking at it theologically, you have the humans, who are the redeemed, and the zombies too far gone to be redeemed, but the largest group by far were the normal zombies who craved their own redemption, and can symbolize your average person.

So glad to hear your thoughts on this! I’ve been avoiding zombie stuff, and now I can see I’m also missing out on a chance for some interesting conversations.

Phyllis, I’m so glad you found it helpful. Yes, the conversations have been very interesting. I’m hoping to try it out in a youth-group setting at some point.

I’ve been getting into zombie fiction recently, partly because I have to write zombie fan fiction based on the video game Left 4 Dead. I’m in a videogame design class, and the two other guys that I’m working with are both Left 4 Dead fans. They wanted to make a custom campaign for Left 4 Dead 2 for our final project.

This campaign I’m writing evokes another theme that I think is strongly evident in all apocalyptic and dystopian fiction, but perhaps even more stongly in zombie fiction — survival. My game design project is a “survival map” — a game type in which the players hold out as long as possible, but there is no way to win, so everyone eventually dies. In the backstory that I’m writing, I’m trying to suggest that no one is immune to zombie infection, and no place is safe.

The canonical Left 4 Dead franchise includes a free comic called The Sacrifice, which naturally is a story about the sacrificial death of one of the “survivors” — the playable characters in the game. I think there’s enough to conclude from these themes that mere survival is not worthwhile. In the end, sacrifice is more important than survival.

These themes are definitely not lacking in common grace!

The Nostalgia Critic had a vlog discussing why zombies were so popular, and one of the bigger points he made was that anymore, the story is less about the monsters and more about how people react to them. The approach angle, especially in The Walking Dead, is more survivalist than straight horror, and it’s more character-driven. And it’s a total playground for ethical debate. Where on the scale from pragmatism to idealism do they fall, and should they fall here or there?

Outstanding analysis and a faithful, penetrating upholding of God’s Word in every circumstance. When we cast God’s Word behind our back, as those young people advocated, we bring ruin upon ourselves. Thanks for standing up for the Truth without fear or compromise. The other thing I’d like to say is the usual Christian approach to zombies, i.e., let’s ignore them completely or indulge a guilty pleasure in silence, applies to all horror fiction regardless of subgenre. The Christian approach is to uniformly pretend horror doesn’t exist and marginalize it as much as possible in the Christian creative community, or to be a silent appreciator. Both of these need to stop. Horror had its birth in the biblical worldview — Shelley’s Frankenstein and Stoker’s Dracula — and the questions it raises, like the zombie subgenre, need to be explored. Not hidden. And anyone who says “Horror can’t glorify God” needs to see the Walking Dead Season 3 episode where Hershel reads from Psalm 91 to his daughters. Think of the millions of unbelieving fans who might not have ever head those Words any other way! Yes, God chose The Walking Dead to be a vehicle for His Word to go forth and be heard. The Word He sent through that episode shall NOT return to Him empty. He is pleased to use even horror. Let’s not therefore hide from it. We might miss something He wants us to hear.

Well said, H.G. !

I’m glad you write articles like this. I try and try to understand the attraction of horror and zombies, but I can’t get past the disgusting ugly.