Reading With Purpose

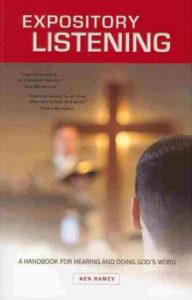

A particular radio ministry is giving away to those who contact them during the month of October copies of Expository Listening by Ken Ramey. I’m not giving an endorsement of the book here because I haven’t read it. I only know that it challenges people who listen to sermons to do so actively, not passively.

A particular radio ministry is giving away to those who contact them during the month of October copies of Expository Listening by Ken Ramey. I’m not giving an endorsement of the book here because I haven’t read it. I only know that it challenges people who listen to sermons to do so actively, not passively.

But the title and the brief description of the book makes me wonder if readers don’t need to be charged in a similar way.

Certainly the idea of reading as an escape has been examined and re-examined here at Spec Faith. Tolkien best clarified the concept, and proponents of speculative literature have embraced his words:

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. (“On Fairy Stories” by J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 20).

As popular as Tolkien’s view of escape in connection with reading speculative literature has become, I question whether many embrace his intent. His comparison of escape enjoyed through reading to escape by a prisoner wishing to go home clearly illustrates his thought—the escape he advocated has a purpose.

As popular as Tolkien’s view of escape in connection with reading speculative literature has become, I question whether many embrace his intent. His comparison of escape enjoyed through reading to escape by a prisoner wishing to go home clearly illustrates his thought—the escape he advocated has a purpose.

I suggest that far too many readers, feeling justified by Tolkien’s words, are content with the escape of the deserter and turn reading into a passive occupation, a form of mindless entertainment.

I think Tolkien would be horrified at such a concept. Clearly the prisoner who escapes is not only leaving one thing, he is attempting to reach somewhere else. In other words, his actions are aimed at changing his circumstances.

Even when he cannot escape, as Tolkien says, his thoughts rightly go beyond guards and prison walls. He is thinking above his circumstances and focusing on what gives him hope and courage.

Reading, I believe Tolkien is saying, should have a similar purpose.

Certainly writers are responsible for infusing meaning into their stories, but then it is up to readers to suss it out. Those satisfied with entertainment will care for little more than the thrill of the read—the tears or laughter the story evoked, the rush the tension generated.

I certainly believe stories should appeal to a reader’s emotions, but if that’s all a person takes away from a novel, they are more akin to the deserter than the prisoner.

Deserters want to get away from the fight. Readers who read for pleasure alone want to get away from the fight. For the Christian, at least, there ought to be more.

We as Christians are bought with a price and no longer are our own. We don’t really have the luxury to be mindless in our approach to stories because we are not deserters. We are prisoners, having some place to go, not just some place to ditch.

But reading as prisoners takes some intention. We need to be on the alert for whispers of truth behind the dialogue of ordinary characters. We should stand as watchmen on the wall looking for potential assault or for the arrival of the kings entourage.

Novelists can include these things, but readers must do the work to uncover them—unless, of course, we miss Tolkien’s point and think escape as a deserter is the same as escape as a prisoner.