The Qualities Of A Hero

What does it mean to be a hero?

Ask ten different people, and you’ll probably end up with a handful of different answers. Every bookworm and movie junkie is well-acquainted with that small word: hero. But down in the dust, dirt, and toil of Storyville, what does this mean?

Ask ten different people, and you’ll probably end up with a handful of different answers. Every bookworm and movie junkie is well-acquainted with that small word: hero. But down in the dust, dirt, and toil of Storyville, what does this mean?

I love poking fun at clichés. Yesterday, the blog post on my site dealt with the defining features of a hero. An appropriate title could have been, “To Be Hero or Cliché? That Is the Question.”

Any time stories are present, clichés—great or small, intentional or accidental—are present. It’s unavoidable. The question is, how will the author, filmmaker, screenwriter add some zest?

Taking the hero stereotype off the wall and examining it reveals that heroes are particularly vulnerable to assaults by the Cliché Monster. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the modern film industry, where we’ve been inundated with a specific type of hero that elevates unimportant qualities over the elements that truly determine one’s level of heroism.

From my perspective, there are two sides of a hero. The external and the internal. Which is more important? Which traits contribute more to the person’s qualifications of hero? Let’s examine both.

The External Hero

Image from xmenmovies.wikia.com

Say “hero” and what happens? A slew of the most handsome, muscular, attractive men in existence pop out of thin air, complete with the requisite cape and “I Am Hero” logo emblazoned across the front of their skin-tight gym shirt—which displays every rise and contour of their muscles like a topographical map.

Yes, that was sarcastic and exaggerated. However, the point remains. What has become of the hero archetype? Hollywood would have us believe it’s comprised in large part of physical appearance. The “WOW, Hugh Jackman is ripped” factor.

I’m not saying this is a bad thing. Some guys can’t help it if they’re well built, and in unique cases—thinking of Captain America here—their impressive physique is part of their identity as a hero.

Yet that only tells half the tale. It only shows us one side of the coin.

If our definition of a hero is someone who will make the ladies swoon, who can be buried beneath a collapsing high-rise and live to tell the tale, whose torso and arms would make excellent training ground for BMX bikers, then we’re sadly mistaken.

External features are important, but they’re the icing on the chocolate cake, not the flour and cocoa that make the cake a cake.

Which brings us to the other side of the coin.

The Internal Hero

Awhile back, I wrote a SpecFaith article titled Strength In Weakness: A Tale of Hobbits and Heroes.

One of the main points was the fact that true strength is found within. Don’t look at the biceps, the haircut, the loads of money, the million-dollar smile to determine the true character of a hero. Look inside.

- Loyalty

- Self-sacrifice

- Love of others

- Courage

- Fortitude

These are some of the attributes of heroes, and they’re infinitely more important than the outward presentation of physical prowess.

Above all, these are the qualities that make a character worthy of the title hero.

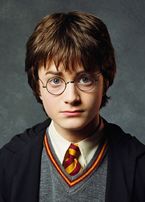

Image from harrypotter.wikia.com

Modern culture insists upon appearances as the standard for judging one’s value. Unfortunately, that misses the mark by a disturbing margin. Now there’s nothing wrong with the Thors and Wolverines of the world, who are gifted both with impressively ripped bodies and the internal traits needed to be a hero.

Yet we should never forget or pass off as second-rate those whose claim to heroism is their internal characteristics. The Frodos and Harrys of the world.

At the end of the day, remove the external bells and whistles, and you still have the makings of a hero. But remove the vital internal qualities, and you have at best a buff dude who’s impartial and at worst a deadly villain.

Hollywood is wrong. What makes a hero isn’t what we see. It’s what they do and the core nature driving those actions.

In your opinion, what are the determining qualities of a hero?

Dat eye-candy, tho

Huge muscles don’t do it for me, though.

Tho’ a good looking actor (on my terms) certainly doesn’t hurt 🙂

If looks made the character a hero, Gaston and Loki would qualify. But that’s why physical beauty must be matched (in my mind, anyway) by honor and other gentlemanly virtues. If they don’t, i don’t care how handsome the character is, I can’t root for them. Sherlock, for instance, anti-social though he is, loves his friends and will do anything for them. Wolverine is the same, he’s this tough guy, and (in the comics) not much to look at, but if you give him a choice between saving his own rear and saving one of his young charges (or Jean) he’ll pick his “Kids” and Jean over himself every time.

I’ll let All-Might give my answer in this clip from one of my favorite new anime/manga, My Hero Academia, as he examines his apprentice’s actions in the entrance exams for Hero school.

What’s interesting is that the list you gave to describe the internal hero- Loyalty, Self-sacrifice, Love of others, Courage, and Fortitude- could also be used to describe a villain.

For instance, a terrorist can be described in these terms. (The “love of others” being those who he/she terrorizes for- a leader, a nation, or a race.)

I think one thing that’s needed to round out the internal hero quality list is a dedication to good. Meaning, the hero willfully chooses that which is good, and noble, and righteous in the morally objective sense.

One example of this is found in one of my favorite comic book characters come portrayed on the big screen; Hellboy.

What’s interesting about Hellboy is that he is a demon- obviously not in the biblical sense- but he willfully denies his evil nature in order to fight for the good. He reject what he is to protect humanity… and kittens.

In first film, in the final moment of the climactic scene (SPOILER ALERT) when Hellboy defeats the bad guy and is asked by his dying enemy why he would not take his rightful place as the destroyer of man and an evil ruler of an dead apocalyptic world, Hellboy simply answers: “I chose”.

That’s awesome.

It’s a very interesting character. (Again, if you set aside the biblical definition of a demon, and just see him as another race of being.)

Anyway, the adherence to morally objective good is essential for a hero, I would say.

I think Steve is onto something here. The difference between a hero and a villain is often precisely a choice to do good rather than harm. I might refine it a bit, since it is not necessarily true that a hero must also be pure and saintly. I think one key indicator of what makes one character a hero and the other a villain is a virtue rarely cited: self-restraint. As Steve said, under certain definitions of ‘love of others’ and ‘self-sacrificing’ a terrorist might fit under definition of a ‘hero’ – which indicates how careful one must be with definitions. Villainy is marked by a willingness to use any means necessary to achieve the desired goal, which may or may not include personal gain (though it typically does), whereas part of heroism is displayed in restraint: not killing the enemy when they are defeated, not taking all possible power for themselves to serve their ‘justified’ cause, trying to limit ‘collateral damage’ or harm to others, or even a readiness to turn turn the situation over to established/traditional authorities when the battle is over, that kind of thing. A hero does not (ideally) seek her/his own power or glory; not quite the same thing as self-sacrifice, but a close cousin thereof. A hero might seek to be King, like Aragorn in Lord of the Rings, or Peter in Narnia, but such a quest is not self-seeking seizing of power but an attempt to restore what has already been established as right and just (and even Aragorn did not really seek to be king, but accepted it as his role when the time came).

I’d add humility and integrity.

The humility could take different forms depending on the circumstances – admitting they’re wrong, deferring to authority, laughing at themself, realising that others are better at something than them, acknowledging the help of others, not boasting…