Travis P here. In contrast to the layout of other weeks, Iâm going to first introduce and later illustrate a post initiated by my fellow Travis (Chapman). In this post, he focuses on the training for âhigh-end capabilities,â which is the term used for highly expensive weapons systems that constitute the most advanced means of fighting that modern nations have. Note that even though the terminology of high-end capabilities has a very 21st Century feel to it, the concept can be applied to speculative stories that mirror the legendary past as well as those set in highly technological futures.

Note also that the type of training this post explores is highly technical. Instead of focusing on training warriors to endure the hardships of up close combat, this kind of training requires mastering the highly advanced weapons systems of high-end capabilities. Whatever those high-end capabilities may be.

Travis C here. Iâd like to introduce a few terms of art. In a modern parlance, high-end warfighting is becoming a buzz term to describe warfighting that is peer-against-peer utilizing advanced technology and tactics. In their time, World War I and II both demonstrated high-end warfighting concepts: incorporation of air combat power, battles for naval supremacy using submarines, convoys, battleships, and aircraft carriers, long-range bombing and artillery strikes, communications advances, etc. Not that we didnât have those things prior to the world wars, but we saw them institutionalized into military structures and a very deliberate application of those powers by the nations involved against rival military forces and to achieve military ends.

WW2 USS Enterprise’s final voyage. Credit: CNN.com

A military capability is intuitive: a capability to conduct a certain kind or set of activities for any number of purposes. My personal background is in submarines, which represent a range of capabilities. We can conduct anti-shipping, anti-surface warfare, submarine-on-submarine warfare, launch missiles ashore, sit off the coast and collect intelligence, transfer goods clandestinely, and create a great deal of uncertainty for a nation. Some of those capabilities are clearly for military purposes (launching torpedoes). Some, however, also serve political purposes (deterrence: we may or may not have a submarine operating in the vicinity of a nation, causing them to consider whether to put a fleet to sea). They also showcase a nationâs military strength as a capital asset.

A âcapital assetâ (we could use other terms, but this one will suffice) is something a nation would have to invest a significant amount of resources into acquiring but demonstrates that nationâs capacity and resolve to have that asset and the potential to utilize it. Letâs consider a non-military example that gets us closer to our science fiction purpose: the United Statesâ space shuttle program. It cost a lot of money to design, build, and operate our shuttles. It takes a lot of engineering and science research and development, worker training, intellectual know-how, political resolve and budgeting, good management, and material resources to get a space shuttle. Once you get a shuttle, it takes highly-skilled, highly-capable and adaptable, best-of-the-best operators to execute the missions we desired the shuttle for. Not everyone can have a space shuttle. The same is true for capital assets in the military. Not every nation can operate submarines, or long-range bombers, or missiles, or fighter jets, or close-combat-supporting helicopters, or satellite networks.

Flying Nazgul. Credit: Figwit via councilofeldrond.com

Clearly many capabilities we know from the world of science fiction will fall into the category of a capital asset. Spacecraft, space stations, and the propulsion systems that power them will likely be a unique class of capability. Think also of those near-future capabilities we know are just over the horizon: artificial intelligence, machine learning, near-instantaneous information availability and communication/connectedness. In the realm of fantasy, many applications of magic might be considered this way. Truly, Gandalf and Saruman represented unique capabilities within their respective forces, and the Ringwraiths represent a whole set of capabilities for Mordor. The oliphants at Pelenor Fields and rock-dropping griffins of King Edmundâs Narnian army may also fall under that heading. Â

While the training of a warrior for close combat will involve physical conditioning, weapons proficiency, and preparation for the psychological and physiological impacts of the battlefield, the operators of these high-end capabilities require something different. While all members of the military receive a basic level of training, those services supporting high-end capabilities will divert the practitioners of those communities into specialized training schools and follow that up with routine integrated training to ensure all the pieces work together.

Letâs again use some examples close to home: Sailors and Airmen. All members of the U.S. military go through some form of basic training, learning the institutions of their respective service, military courtesies, and by and large spending a great amount of effort in breaking down individualism and growing a team-oriented attitude among recruits. This will have important consequences later.

The majority of Sailors and Airmen who enter service do so knowing the field of work they will participate in. After basic training they will depart for a series of training activities to learn those specialized skills. It might be many months before they are ready to join an operating platform or unit and begin to apply those skills as an apprentice-level practitioner. You would expect an aircraft maintainer, nuclear power plant operator, missilier, combat system technician and operator, etc., so need to learn the basics of the systems before they head to a vessel or aircraft squadron that will deploy.

US Air Force missileers in training. Credit: AF.mil

Once basic and specialized training is complete they will report to an operating unit where they will apply those skills in a graded manner, maturing from apprentice operators under the guidance of more senior and experienced folks and gaining real-world expertise. Itâs here that integration occurs, since the numerous specialties come together to form a single operating unit. A warship is not only the sum of its parts (propulsion plant, sensors, weapon systems, living quarters for the crew, etc.), but the true impact of that platform is in the synergy of a well-trained, trusting, and focused crew. The same can be said for a squadron of aircraft, a cadre of missileers, the crew of a submarine, or any other capital asset that requires multiple skills to effectively operate.

Lastly, those capital assets must be exercised in simulated environments to ensure the crews know what to do, when to do it, and ensure that routines become second nature so that actions occur without fail in times of confusion and duress like combat. During the period leading up to a deployment, and with some degree of regularity at all times, teams will practice routines and drill themselves on the breadth of their capabilities. Emergency action drills, equipment and system casualty drills, battle stations, launch procedures, and simulated wargames to test the ability of the team to execute their missions in the midst of anticipated challenges will ensure operators are ready for as many expected situations as possible. More importantly, it prepares them for the unknown things that might happen by building a level of readiness and preparedness that will be adaptable to circumstances that arise.

That might seem like a ironic combination, but high-end warfighting is based on a balance between rote mechanical routines that reduce the operatorâs need to think (donât think, just act) with a demand for creativity, adaptability, and ingenuity to bring those skills to bear depending on the situation.

Travis P again. I hope readers are grasping the impact of what Travis C said and how that affects speculative fiction stories. We may tend to think of the military capacities of a nation as being even–but in fact the difference between the minimum technology a nation may have and its most advanced weapons can be extreme.

Egyptian-style chariot. Credit: Joe Alblas © Lightworkers Media / Hearst Productions Inc.

These contrasts have always existed–for example, in the world of the Hebrew Scriptures, the chariot was the most elite and highly technical weapon of its era. Israelites, who especially at first fought mostly with untrained levies of troops, could not afford to create a permanent warrior caste or to pay professional warriors with the skills to operate chariots. Nor did they have the specialized skills involved in building chariots. So it wasnât until after the time of David the King that the Israelites had any chariots at all, and they never had many in relation to other nations.

Soviet Union Typhoon submarine. Credit: Wikipedia

But the larger a nation is and the more technologically developed its world is, the bigger the potential difference is between high-end capacities and the minimum abilities to fight that a nation has. The Soviet Union had poorly trained draftees it could barely manage to house and feed at the low end of its abilities and also ballistic nuclear submarines worth the equivalent of billions of US dollars on the high end. A united world in a futuristic science fiction universe could mostly be at a medieval level of technology–but might be able to pool enough resources as a planet to buy a starship or two and might manage (with the help of more advanced races) to provide the training required to run it or them. And that one or two starship(s) might easily have more military capacity than all of the rest of the world combined.

Credit: starwars.com

The classic example of a high-end capability in familiar speculative fiction would be the Death Star. While Tie Fighters and Imperial Star Destroyers require plenty of specialized training, the Death Star by itself exceeded the capacity of the entire Rebel fleet (even though it was vulnerable to them due to an accidentally-on-purpose flaw as seen in Rogue One). Some of the uniforms a moviegoer will see on the Death Star are nowhere else in Star Wars–clearly these were specialists trained to operate the Death Star and the Death Star alone. Operating the Death Star obviously would require a great deal of highly technical training that would have very little in common with the battle hardening required of elite warriors that our previous posts have discussed. Yet the Death Star far exceeds the destructive capacity of all the elite hereditary warriors of that story universe combined, the Jedi Knights (not even working together could all the Jedi blow up a planet).

Death Star crew at work. Credit: Flickriver.com

Writers of epic fantasy, donât think this article doesnât apply to you! When we start talking about magical capabilities, clearly the training of an elf or wizard that requires thousands of years to master represents high-end capabilities that are in a way every bit as advanced as those found in a technological society. Though wizards are generally portrayed as being more generalized than technologically advanced warriors, thereâs no particular reason wizards couldnât be portrayed as highly specialized instead.

UK Ministry of Magic Logo (Harry Potter).

Credit: http://harrypotter.wikia.com

Harry Potter represents an interesting case. Magic is clearly an integral part of the wizarding world and training of wizards is expected. Students actually learn basic skills in schools (Defense Against the Dark Arts) and a class of specialized warrior-constables exists in the Aurors. Do we see that level of sophistication when the war opens up in the last few books? Or is it every wizard for himself or herself?

Jaeger “Striker Eureka.” Credit: scifi.stackexchange.com

Another example of high-end capabilities and the training used to support them can be found in Pacific Rim with the Jaegers. Clearly these are complex devices (even if not wholly realistic), requiring significant investment and lots of support structure. Even though the storyline focused on characters who were their pilots, these were obviously not the only personnel required to develop Jaegers.

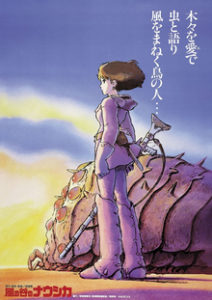

NaussicaÀ and the Valley of the Wind poster by Yoshiyuki Takani

We also see some crossovers into the realm of steampunk-ish worlds. Mortal Engines, David Webersâ Off Armageddon Reef (a low-tech world featuring an advanced navy and a cybernetic protagonist), Studio Ghibliâs NaussicaĂ€ and the Valley of the Wind (featuring a few high-end weapons), etc.

What are your thoughts on the topic of military high-end capabilities and the training required to support them?

Jesus, born of Mary, was God’s first step onto earth in the skin of Man. It was the beginning, the realization of the promise, “For a child will be born to us, a son will be given to us.” Everything that night of Jesus’s birth was a shout—the great, glorious plan of redemption, worked out before the foundations of the world, was unfolding. It was being revealed to us who, through Him, would become believers in God.

Jesus, born of Mary, was God’s first step onto earth in the skin of Man. It was the beginning, the realization of the promise, “For a child will be born to us, a son will be given to us.” Everything that night of Jesus’s birth was a shout—the great, glorious plan of redemption, worked out before the foundations of the world, was unfolding. It was being revealed to us who, through Him, would become believers in God.

Yet there is, implicit in most of these stories, a sense of journey and a sense of mystery. We donât know where the ghosts are going when they are finally ready to leave, but they are going somewhere; we donât know what happens when the twilight over the city of empty streets ends, or where Death is leading the old woman. Many stories affect to peer through the great veil of death, but few pretend to tear it down. We are ignorant even in our stories, and in that ignorance is mystery, and in that mystery is hope.

Yet there is, implicit in most of these stories, a sense of journey and a sense of mystery. We donât know where the ghosts are going when they are finally ready to leave, but they are going somewhere; we donât know what happens when the twilight over the city of empty streets ends, or where Death is leading the old woman. Many stories affect to peer through the great veil of death, but few pretend to tear it down. We are ignorant even in our stories, and in that ignorance is mystery, and in that mystery is hope.

Featured review: Enclave

Featured review: Enclave

Even in Christian fiction, the cry seems to be for fiction that reflects reality, even when the story is supernatural or science fiction or fantasy. The reality factor is the idea that the story reflects the world as we know it in some way. And certainly what we know is something of an odd mixture of good and evil, as Jonathan Robb noted in his article. There are no Mordors run by evil-eye rulers that hold the world under its control by making war on Gondor There are no Rangers who roam the world to fight for the right and protect the hapless hobbits who are clueless of the conflict raging around them.

Even in Christian fiction, the cry seems to be for fiction that reflects reality, even when the story is supernatural or science fiction or fantasy. The reality factor is the idea that the story reflects the world as we know it in some way. And certainly what we know is something of an odd mixture of good and evil, as Jonathan Robb noted in his article. There are no Mordors run by evil-eye rulers that hold the world under its control by making war on Gondor There are no Rangers who roam the world to fight for the right and protect the hapless hobbits who are clueless of the conflict raging around them.

Thankfully we have a resource:

Thankfully we have a resource: