Fourth âDoctorâ Season Brings New Alien Agendas, Part 1

More hideously scary monsters are coming to the new season 4 of the smashing British sci-fi series Doctor Who. Like the Cybermen, a race of metallic soulless humanoids who want to âupgradeâ all humans to be like them, this threat arises from a surprising source and threatens the existence of planet Earth, by compelling people to be subject to certain extraterrestrial modes of thought.

More hideously scary monsters are coming to the new season 4 of the smashing British sci-fi series Doctor Who. Like the Cybermen, a race of metallic soulless humanoids who want to âupgradeâ all humans to be like them, this threat arises from a surprising source and threatens the existence of planet Earth, by compelling people to be subject to certain extraterrestrial modes of thought.

And itâs courtesy of none other than Doctor Whoâs very executive producer and head writer, Russell T. Davies.

âWait wait wait wait!â

While I say that, please imagine me holding up my hands in a faux-panicked manner, reminiscent of the Tenth Doctor, right before I whip out a clever solution to avoid being killed. This is because, unlike some Christian writers and culture pundits, I seem to find myself unafraid of Daviesâ own ideological invasions.

âUpgrading is compulsoryâ

Davies, who re-launched the new TARDIS and its time-traveling, world-saving Time Lord occupant(s) in 2005, is âthe most influential gay man in Britain,â according to an April 6 London Independent article. Well, I kind of already knew that. But furthermore â well, especially if you have Christian friends who enjoy sending you dozens of email forwards, youâve surely heard of British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins? Heâs the same guy who looks stupid in Ben Steinâs anti-evolutionary-dogma documentary Expelled. Well, it seems Dawkins is having a cameo in the new Doctorâs season 4.

Davies, who re-launched the new TARDIS and its time-traveling, world-saving Time Lord occupant(s) in 2005, is âthe most influential gay man in Britain,â according to an April 6 London Independent article. Well, I kind of already knew that. But furthermore â well, especially if you have Christian friends who enjoy sending you dozens of email forwards, youâve surely heard of British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins? Heâs the same guy who looks stupid in Ben Steinâs anti-evolutionary-dogma documentary Expelled. Well, it seems Dawkins is having a cameo in the new Doctorâs season 4.

âPeople were falling at his feet,â says Davies, creator of the BBCâs flagship show. â[. . . I]t was Dawkins people were worshipping.â

As writer and executive producer of Doctor Who, Davies often plays with religious imagery (from a cross-shaped space station to robot angels with halos), but heâs a fervent believer in Dawkins. âHe has brought atheism proudly out of the closet!â

Later, Davies unabashedly unveils the purpose behind Captain Jack Harkness â an openly âbisexualâ character who pretty much hits on everybody, guy, girl or extra-Earth species. The idea is not only to help people tolerate homosexual beliefs, but to encourage children to âcome out of the closetâ themselves. âIf there is one kid now doing that, then in 10 yearsâ time there will be thousands of kids, and 10 years after that, every kid who wants to will be doing that,â Davies said. âIsnât that brilliant?â

Intriguing! Somehow the image of the Cybermen enters my mind. â[We are] the next level of mankind. We are Human Point Two. Every citizen will receive a free upgrade. You will become like us. . . . Upgrading is compulsory.â Meanwhile, as for lingering cultural opposition to becoming one with Cybermen? âDe-lete. De-lete. De-lete.â

The heart of the TARDIS

One might be a bit unsure why Iâm not bothered about this stuff. Is there something wrong with me? Am I a compromising Christian? perhaps one of those quasi-backsliders whoâs just being deceived by awesome characters, spectacular special effects and epic good-versus-evil storytelling?

Itâs that last element, actually, that seems the best reason. Because while Davies and other writers are putting in evolutionary and even gay-rights junk, theyâre also putting in really âfantastic!â messages of redemption, either intentionally or incidentally.

Though the program has its âmomentsâ â innuendo here, a double entendre there â and is based solidly in an evolutionary, everything-supernatural-is-just-advanced-science view, the heart of the TARDIS pulses with remnant energy of a very Judeo-Christian worldview, similar to the warp core of the starship Enterprise. In the Doctorâs adventures, conformity, racism, and evil domination are upended and destroyed. True love, care for people and devotion are upheld. The Doctor is sorry when he cannot save lives â or is forced to take one â and overjoyed when âeverybody lives!â as he exclaims in the finale of The Doctor Dances.

But then, goes a legitimate argument, canât other religions find hints of their views in Doctor Who? And doesnât it directly oppose Christianity with ideas such as that of The Satan Pit, which is that thereâs just one demonic creature in deep space, sending out thought waves that make all kinds of religions believe there really are more-powerful devils and monsters?

Well, perhaps. And itâs true that general-issue moral messages do not make a story Christian. But if we dismiss the Doctor as void of Christian virtue, then we might as well also throw out a lot of âChristianâ-labeled books and movies that also imply humans are decent and God-fearing on their own, without much input from Him. Anything that doesnât directly reference the message of Redemption â that Christ, the Creator/Savior, died to save sinners who deserve and merit nothing from Him on their own â is not truly Christian.

And itâs that message of redemption that makes Doctor Who imbued with Christian influence â a topic Iâll be exploring further in the second installment of this short serial.

(In closing, though, hello again to the Spec-Faith contributing âstaffâ and its readers. Yes, I have been absent for a time, traveling the universe, but Iâve just recently returned to this planet and I hope I can stay for a while. Thanks for your patience, and I hope to be around more in the coming months!)

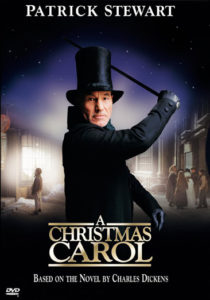

However, Iâm willing to suppose A Christmas Carol would have a place in the Timeless. Itâll share shelf space in Heavenâs libraries along with The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and multiple other novels that broke ground for new growth instead of following in the same tired, crusty furrows.

However, Iâm willing to suppose A Christmas Carol would have a place in the Timeless. Itâll share shelf space in Heavenâs libraries along with The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and multiple other novels that broke ground for new growth instead of following in the same tired, crusty furrows.