Retelling Biblical Stories For A Modern Audience, Part 2

The ancient Jews loved to retell their Bible stories with embellishments. And they did so, not with a disdain for âthe facts of history,â but rather with deep respect for the original message as they understood it. As scholar George Nickelsburg explains, they wanted to âexpound sacred tradition so that it speaks to contemporary times and issues.â1 Biblical scholar Peter Enns adds, âIt is a characteristic of ancient retellings of Scripture that the exegetical traditions incorporated in to these retellings are not clearly (if at all) marked off from the Biblical texts. The line between text and comment was often blurred, so much so that the two often went hand in hand.â2

The ancient Jews loved to retell their Bible stories with embellishments. And they did so, not with a disdain for âthe facts of history,â but rather with deep respect for the original message as they understood it. As scholar George Nickelsburg explains, they wanted to âexpound sacred tradition so that it speaks to contemporary times and issues.â1 Biblical scholar Peter Enns adds, âIt is a characteristic of ancient retellings of Scripture that the exegetical traditions incorporated in to these retellings are not clearly (if at all) marked off from the Biblical texts. The line between text and comment was often blurred, so much so that the two often went hand in hand.â2

Thanks to manuscript discoveries in recent centuries, we now have access to many of these Jewish retellings of Bible narratives, some of which include Jubilees, The Genesis Apocryphon, The Testament of Moses, The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Books of Adam and Eve, and others. In these non-canonical texts we are retold, with creative embellishments, various episodes in Biblical history, from Adam and Eve, to Noah, through Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to Moses and more.

But one of the most fascinating of these texts is the book of 1 Enoch. Written some time around the third to second century B.C., this text has both haunted and been cherished by the Christian Church through its history. It is apocalyptic in genre—cloaking warnings of judgment in dream visions, parables, and complex metaphoric imagery. But it is most well known for its detailed elaboration of the Genesis 6 story about the Sons of God (called âWatchersâ) and their intimate involvement in the cause of the Noachian Flood. There it describes in much detail the Watchers as fallen angels revealing occultic secrets to mankind, having intercourse with human women, and birthing giants who cause terror across the land.3

Just what contemporary situation is Enoch referring to in his apocalyptic prose? Some scholars think its origin around the time of the Maccabean revolt in 167 B.C. makes it a prophetic denunciation of the religious corruption of the Jewish world by its Hellenistic occupiers.4 This pagan occupation would soon be overthrown by the victorious exploits of Judas Maccabeus and his brothers, returning Judaism to its purity and inspiring the origins of the festival of Hanukkah. So the author of Enoch was engaging in a rich tradition of retelling a Biblical story of judgment on a corrupted and compromised world as a moral warning for those of his own time. It was also part of this tradition to attribute their manuscripts to such historical luminaries as Enoch himself, not as a lie but as a literary technique that reinforces the significance of the message.

Though 1 Enoch is not in the Western canon of Scriptures, it is in the Eastern Ethiopic canon, and was respected by Christian scholars and authorities throughout the early church. It was never considered heretical by church authorities. But the real kicker is that the New Testament even refers favorably to the book of Enoch in 1 Peter 3:19-20, 2 Peter 2:4-10, and Jude 1:6-14.

Firstly, Jude quotes the book of 1 Enoch outright when he writes of false teachers corrupting the church:

[T]hat Enoch, the seventh from Adam, prophesied, saying, âBehold, the Lord comes with ten thousands of his holy ones, to execute judgment on all and to convict all the ungodly of all their deeds of ungodliness that they have committed in such an ungodly way, and of all the harsh things that ungodly sinners have spoken against him.

Here is the text from the actual book of 1 Enoch 1:9 that Jude is quoting:

And behold! He cometh with ten thousands of His holy ones to execute judgement upon all, and to destroy all the ungodly: And to convict all flesh of all the works of their ungodliness which they have ungodly committed, and of all the hard things which ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.5

But not only does Jude explicitly quote a passage out of 1 Enoch regarding God coming with the judgment of his divine council of holy ones (Sons of God), but all three texts refer to the Enochian notion of the angelic Watchers being punished for co-habiting with humans as a violation of the divine/human separation, another main theme of 1 Enoch.6

And just in case anyone would question this fantastical interpretation, 2 Peter and Jude quote a common doublet that linked the sexual violation of the Watchers (and their giant progeny) with the sexual violation of the inhabitants of Sodom who sought sexual intercourse with angels. The common theme of both instances was the violation of heavenly and earthly separation of flesh.

Here is the list of texts containing this doublet of connection that Jude and Peter allude to. It is not found anywhere in the Old Testament, but only in non-canonical ancient Jewish texts:

Jude 6:6-7

And angels who did not keep their own domain, but abandoned their proper abode, He has kept in eternal bonds under darkness for the judgment of the great day, just as Sodom and Gomorrah and the cities around them, since they in the same way as these indulged in gross immorality and went after strange flesh, are exhibited as an example in undergoing the punishment of eternal fire. [emphases here and in the following passage added]

2 Peter 2:4-10

For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to pits of darkness, reserved for judgment; and did not spare the ancient world, but preserved NoahâŠand if He condemned the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah to destruction by reducing them to ashes, having made them an example to those who would live ungodly lives thereafter⊠then the Lord knows how toâŠkeep the unrighteous under punishment for the day of judgment, and especially those who indulge the flesh in its corrupt desires and despise authority.

Sirach 16:7-8

He forgave not the giants of old,

Who revolted in their might.

He spared not the place where Lot sojourned,

Who were arrogant in their pride.7

Testament of Naphtali 3:4-5

[D]iscern the Lord who made all things, so that you do not become like Sodom, which departed from the order of nature. Likewise the Watchers departed from natureâs order; the Lord pronounced a curse on them at the Flood.8

3 Maccabees 2:4-5

Thou didst destroy those who aforetime did iniquity, among whom were giants trusting in their strength and boldness, bringing upon them a boundless flood of water. Thou didst burn up with fire and brimstone the men of Sodom, workers of arrogance, who had become known of all for their crimes, and didst make them an example to those who should come after.9

Jubilees 20:4-5

[L]et them not take to themselves wives from the daughters of Canaan; for the seed of Canaan will be rooted out of the land. And he told them of the judgment of the giants, and the judgment of the Sodomites, how they had been judged on account of their wickedness, and had died on account of their fornication, and uncleanness, and mutual corruption through fornication.10

The New Testament literary reference to non-canonical sources does not mean those sources are the inspired Word of God, nor that everything in them is true, but it certainly does illustrate that the Bible itself interacts meaningfully and favorably with interpretive exegetical traditions that engage in imaginative embellishment of Biblical stories. Unlike some Christians, God does appreciate creative imagination.

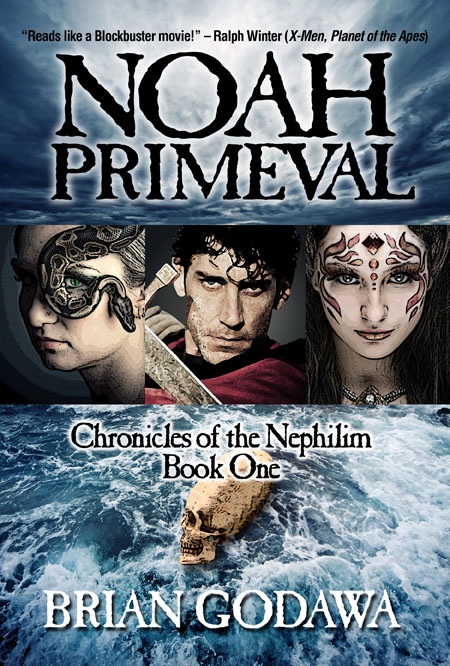

Noah Primeval is a story that carries on that ancient tradition of retelling Biblical stories into our own generation. It builds on the Enochian theme of the Watchers, giants, and occultic secrets but adds to it additional fantastic but Biblical oriented imagery of the divine council of the Sons of God, Leviathan, Sheol, and the ancient Near Eastern Biblical view of a three-tiered universe. But it also incorporates Sumerian and other Mesopotamian mythical elements in order to subvert them into the service of the narrative. Itâs all positively primeval.

– – – – –

1 George W. E. Nickelsburg and Klaus Baltzer, 1 Enoch : A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, 29 (Minneapolis, Minn.: Fortress, 2001).

2 Peter Enns, Exodus Retold: Ancient Exegesis of the Departure from Egypt in Wisdom 15-21 and 19:1-9, (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1997), 35.

3 1 Enoch chapters 1-36 is called the âBook of the Watchersâ and deals with this material. The book of Jubilees is another respected text that contains a detailed retelling of the Noah story with Watchers cohabiting with women, and birthing giants. See Jubilees 4-10 and 20:4-5.

4 Charlesworth, James H. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 1. New York; London: Yale University Press, 1983, 8.

5 Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, ed. Robert Henry Charles, Enoch 1:9 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2004).

6 1 Enoch 10:12; 19:1 âBind them [the fallen Watchers] for seventy generations underneath the rocks of the ground until the day of their judgment and of their consummation, until the eternal judgment is concludedâŠâHere shall stand in many different appearances the spirits of the angels which have united themselves with women. They have defiled the people and will lead them into error so that they will offer sacrifices to the demons as unto gods, until the great day of judgment in which they shall be judged till they are finished.â James H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 1, 1 En 10:12; 19:1 (New York; London: Yale University Press, 1983). 1 Peter writes of Christ during his death making âproclamation to the spirits now in prison, who once were disobedient, when the patience of God kept waiting in the days of Noah.â

7 Apocrypha of the Old Testament, Volume 1, ed. Robert Henry Charles, Sir 16:7â8. Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2004, 372.

8 Charlesworth, James H. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 1. New York; London: Yale University Press, 1983, 812

9 Apocrypha of the Old Testament, Volume 1. ed. Robert Henry Charles, 3 Mac 2:5. Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2004, 164.

10 Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament Volume 1. ed. Robert Henry Charles. Bellingham, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 2004, 42.

– – – – –

Brian Godawa is the author of the new Biblical fantasy novel, Noah Primeval, now available for purchase on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To see a trailer, read an author interview, sign up for free chapters, and learn more information about the Chronicles of the Nephilim, visit the Noah Primeval web site.

Brian Godawa is the author of the new Biblical fantasy novel, Noah Primeval, now available for purchase on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To see a trailer, read an author interview, sign up for free chapters, and learn more information about the Chronicles of the Nephilim, visit the Noah Primeval web site.

Mr. Godawa is also the award-winning screenwriter of the feature film To End All Wars, starring Kiefer Sutherland. In addition, he authored the popular book Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment (IVP). Visit his web site for films and other books and free articles.

Questions remain, for sure. Will God make new beings? (That topic is still going,

Questions remain, for sure. Will God make new beings? (That topic is still going,

No, I’m not talking about

No, I’m not talking about