Hoo-ahhh. Men apparently run the media, film, advertising, and comic-book industries. Men made Disney stop making movies with princess in their titles, even if the princess is from Mars. In science fiction and fantasy, men seem dominant. (Most notable exception: Christian fiction readers?)

I say this not to chest-thump, but because in this series, women face discrimination. Only one column discussed female caricatures. This is my second about male ones.

Intermittent inequalities like that may be inevitable. Men and women are different but equal, whether equal in their rebellion against God (Rom 3:23), or equal in their status as His adopted children (Rom. 8: 15-16).

Thanks for the coffee, yeoman.

Thus, in one era, women may be victims to over-veneration or else stereotyping, such as the infamous gals of the original Star Trek series. (Miniskirts! In space!)

Whereas in another era, people may get sick of it and decide itâs payback time. Now all our TV shows will be very original and stereotype men! (However, the first few Star Trek: The Next Generation episodes actually tried to put men in miniskirts. In space.)

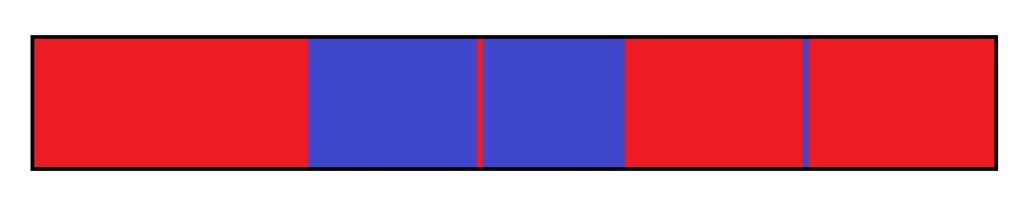

Eventually, no matter which stereotypes each gender receives, either in nonfiction or in fiction, things even out. Thatâs no cause for stepping back and not rebutting stereotypes, but itâs also reassuring. So long as storytellers are writing about realistic people, with all their potentials, positives, and negatives, and not merely trying to build a new character machine thatâs improved on an old model, more stories will have depth.

Still, many readers have personal gripes with caricatured males in fiction, a very diverse assortment of them â from the bumbling sitcom dad, to the evil business industrialist, to the bumbling and evil talk-radio host. On these we cannot now speak in detail. So letâs focus more on tropes with testosterone, or without it, in fantasy and sci-fi:

Stock males

These guys stand around and arenât very effective. They may be extras, or soldiers, or evil henchmen â has anyone ever employed evil henchwomen, after all? (But oddly enough, my evidently progressive word processor believes henchwomen is a word.)

These guys stand around and arenât very effective. They may be extras, or soldiers, or evil henchmen â has anyone ever employed evil henchwomen, after all? (But oddly enough, my evidently progressive word processor believes henchwomen is a word.)

Perhaps we shouldnât nitpick on these bulk-ordered blokes, though. Perhaps every story canât make every single male character into a fleshed-out, four-dimensional human. But if we tried to find a male equivalent to the stock-female character who exists mainly to be eye candy, I think this would be it.

Examples: Video-game mini-bosses; armies recruited from villages; stormtroopers.

Gender-neutrals

Captain Jack Sparrow: (grimacing) âYouâre not a eunuch, are you?â

If the speculative thing doesn't work out, I can always turn to the Dark Side.

Without getting into that whole homosexuality issue, this male character is, from what Iâve read, prevalent in other fiction genres. Heâs a man who behaves like a woman â or at least doesnât directly show many characteristics, perhaps less-popular ones, intrinsic to men. Heâs the kind of guy who stands on the cover of a prairie romance novel, in the background, looking just as forlorn as the main female character in the foreground. Heâs an emotional guy. (Not gay!) Or he might be burying the pain of his past and need to find someone who can help him, perhaps a woman of like mind. (But not gay!)

However, Iâve also seen him in speculative novels. A prime example: The Guy Who Never Notices Womenâs Bodies Below Their Necks. Iâm not talking about rubbing-our-faces-in-it-to-be-Gritty lust descriptions here; rather, Iâm talking about mentions of even Godly attraction, even to oneâs own wife. Some speculative novels avoid this like Andorian plague. Iâm looking at you, Left Behind series (which I otherwise still like).

This male caricatureâs closest match might be the action-hero warrior woman I used to âkick offâ (har!) this series. While that is a man in a womanâs body, this is the reverse.

Examples: Buck Williams, from the Left Behind series; that guy from the novel I wonât name who entered a parallel-world version of the Playboy Mansion but was apparently not tempted by what he saw (in fairness, this could have been publisher constraints).

Bad boys

This one could result in a whole column on his own. Conversely, Iâm not sure I even need to say much more beyond the label and a few examples. What is it about bad-boy characters that appeals to readers or viewers so much â especially women?

This one could result in a whole column on his own. Conversely, Iâm not sure I even need to say much more beyond the label and a few examples. What is it about bad-boy characters that appeals to readers or viewers so much â especially women?

Examples:

- Tony Stark / Iron Man. Stan Lee was stunned at response to this âbad boyâ hero. âOf all the comic books we published at Marvel, we got more fan mail for Iron Man from women, from females, than any other title,â he said. (Source.)

- Edward Cullen. Need I say more? Insert mocking âsquee! he wants to suck my blood but stops himself because he loves me so much; how romantic!â comment.

- Richard Maxwell. Does anyone remember him? He was one of the less-frequent but most popular characters on the Christian radio drama Adventures in Odyssey, a teen hacker and henchman who eventually repented and sought forgiveness.

Closest feminine equivalent: the wily and seemingly âinnocentâ villainâs girlfriend, such as Harley Quinn from Batman: The Animated Series (who was herself preceded by vixens from older Batman comics and the 1960s TV series), who sometimes really wants to help the Caped Crusader, but inevitably returns to the villainâs side.

I wonder if some of the appeal of âbad boyâ characters is not only a reaction against gender-neutral males, in stories or in reality, but a twisted attempt to imitate the ultimate God-Man Who is both loving and nurturing, and just and wrathful.

Men-children

Though I donât see these often in speculative stories, I include them here as a caution: thereâs a chance that men-children may be in the audience of such stories. Yes, many people exaggerate the stereotype of slackers in their parentsâ basements, who play their video games and accomplish little in their non-virtual lives. But they do exist. Iâve met them. I also canât laugh very hard at the internet comics that either mock or bewail their existence. Yet I wonder: what if such a man-child was pulled into a real fantasy world? (Dibs.)

Though I donât see these often in speculative stories, I include them here as a caution: thereâs a chance that men-children may be in the audience of such stories. Yes, many people exaggerate the stereotype of slackers in their parentsâ basements, who play their video games and accomplish little in their non-virtual lives. But they do exist. Iâve met them. I also canât laugh very hard at the internet comics that either mock or bewail their existence. Yet I wonder: what if such a man-child was pulled into a real fantasy world? (Dibs.)

Feminine equivalent: Is there one? If there is, should I even say that word on radio?

Examples: Any âmanâ in a raunchy âcomedyâ film with a title in big red âfunnyâ letters.

The Ăbermensch

As more Christian men and women, in particular, wake up to the irritants of feminism-influenced characters, we will likely see more of these in our fiction: the ultimate man, a faith-based superman. He may have flaws, but eventually defeats evil, lives radically, recycles the money he spends on his little girlâs heart medication so he can donate more to world missions â from the cardboard box where he lives â and daily saves the day.

As more Christian men and women, in particular, wake up to the irritants of feminism-influenced characters, we will likely see more of these in our fiction: the ultimate man, a faith-based superman. He may have flaws, but eventually defeats evil, lives radically, recycles the money he spends on his little girlâs heart medication so he can donate more to world missions â from the cardboard box where he lives â and daily saves the day.

Last week, I quoted from a Christian movie in which a character could be seen as acting like this. But maybe we do need a few stories like this, before things begin to level off?

The Ăberwomensch would be the ultimate-homemaker or power-girl single woman.

Examples: Some guys from the above-mentioned movie (possibly!); potential future Christian fiction.

Prophesied Heroes⢠(part 2)

I must mention this one for this reason: this is probably the most prevalent male caricature in Christian science fiction and fantasy. My definition, from last week:

I must mention this one for this reason: this is probably the most prevalent male caricature in Christian science fiction and fantasy. My definition, from last week:

A poor young man, likely orphaned, who according to ancient prophecy must defeat evil and fulfill Destiny.

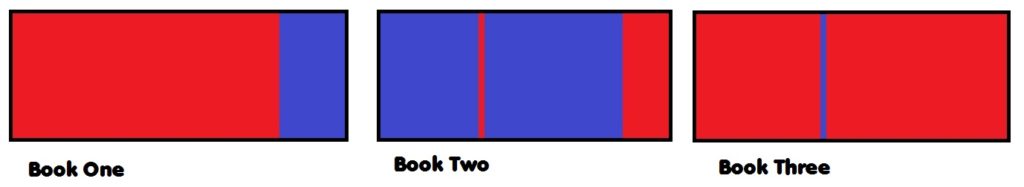

For that, we can likely thank John Carter (initials, anyone?); Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy from Narnia; and the Harry Potter series. The first started the modern fantasy/sci-fi genre. The second, though, is more influential for Christians, and particularly inspired the âyouth from our world/with humble beginnings who is really a king/queenâ idea.

Now I must nitpick my original nitpick. I donât want to see these characters go away. Why not? Because theyâre all based ultimately on Jesus, the real youth from our world, but really another, Who had humble beginnings but was truly the prophesied King. Do I want to see His image scoffed at as only a trope? Or for storytellers to be so âoriginalâ that they make heroes out of superior men who never had humble beginnings? No way.

At the same time, in some of the Christian speculative novels Iâve read, even newer ones, I keep finding heroes with whom I canât identify. I canât easily come alongside the human hero to see myself â as a longtime Christian and attempting âheroâ in this world â as his âbrother.â Instead I keep finding another man I want to parent.

When will he come to true faith? Doesnât he get that this worldâs version of God wants him to fulfill prophecy? In a world like this, why wouldnât he want to go fight and be awesome!

Again, please donât misunderstand: I donât want these characters gone. Given the power, I would not institute any affirmative-action program that would lock humble-farmboys-destined-for-greatness out of fiction. I do think, however, we could use some diversity.

Yet Iâm convinced this resolution lies not in steroid shots to characters, or extra caffeine in authors, but in authorsâ personal growth in Christ â going beyond nonfiction tropes into deeper doctrine magic, applied to real life. That will ultimately make real men in our stories â men who may sometimes do nothing, struggle or have emotional needs, act like âbad boys,â act like children, or make choices and Fulfill their Destinies.

Next week: final series thoughts. What are your thoughts now?

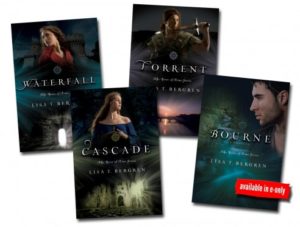

Seriously, head to B&N and youâll see the shelves. There are vampires, werewolves, angels, demons, half-angels, half-demons, dark angels, trolls, etc. Fairies and mermaids, while not quite so dark, get their share of play too. Why are kids drawn to these characters? Because theyâre seeking something bigger than they are. A world beyond the known.

Seriously, head to B&N and youâll see the shelves. There are vampires, werewolves, angels, demons, half-angels, half-demons, dark angels, trolls, etc. Fairies and mermaids, while not quite so dark, get their share of play too. Why are kids drawn to these characters? Because theyâre seeking something bigger than they are. A world beyond the known. Lisa T. Bergren is the author of over 35 books with a combined sale of more than two million copies. She lives in Colorado Springs, Colorado, with her husband and three kids, but constantly daydreams about her next trip to Italy.

Lisa T. Bergren is the author of over 35 books with a combined sale of more than two million copies. She lives in Colorado Springs, Colorado, with her husband and three kids, but constantly daydreams about her next trip to Italy.

These guys stand around and arenât very effective. They may be extras, or soldiers, or evil henchmen â has anyone ever employed evil henchwomen, after all? (But oddly enough, my evidently progressive word processor believes henchwomen is a word.)

These guys stand around and arenât very effective. They may be extras, or soldiers, or evil henchmen â has anyone ever employed evil henchwomen, after all? (But oddly enough, my evidently progressive word processor believes henchwomen is a word.)

This one could result in a whole column on his own. Conversely, Iâm not sure I even need to say much more beyond the label and a few examples. What is it about bad-boy characters that appeals to readers or viewers so much â especially women?

This one could result in a whole column on his own. Conversely, Iâm not sure I even need to say much more beyond the label and a few examples. What is it about bad-boy characters that appeals to readers or viewers so much â especially women? Though I donât see these often in speculative stories, I include them here as a caution: thereâs a chance that men-children may be in the audience of such stories. Yes, many people exaggerate the stereotype of slackers in their parentsâ basements, who play their video games and accomplish little in their non-virtual lives. But they do exist. Iâve met them. I also canât laugh very hard at the internet comics that either mock or bewail their existence. Yet I wonder: what if such a man-child was pulled into a real fantasy world? (Dibs.)

Though I donât see these often in speculative stories, I include them here as a caution: thereâs a chance that men-children may be in the audience of such stories. Yes, many people exaggerate the stereotype of slackers in their parentsâ basements, who play their video games and accomplish little in their non-virtual lives. But they do exist. Iâve met them. I also canât laugh very hard at the internet comics that either mock or bewail their existence. Yet I wonder: what if such a man-child was pulled into a real fantasy world? (Dibs.) As more Christian men and women, in particular, wake up to the irritants of feminism-influenced characters, we will likely see more of these in our fiction: the ultimate man, a faith-based superman. He may have flaws, but eventually defeats evil, lives radically, recycles the money he spends on his little girlâs heart medication so he can donate more to world missions â from the cardboard box where he lives â and daily saves the day.

As more Christian men and women, in particular, wake up to the irritants of feminism-influenced characters, we will likely see more of these in our fiction: the ultimate man, a faith-based superman. He may have flaws, but eventually defeats evil, lives radically, recycles the money he spends on his little girlâs heart medication so he can donate more to world missions â from the cardboard box where he lives â and daily saves the day. I must mention this one for this reason: this is probably the most prevalent male caricature in Christian science fiction and fantasy. My definition, from

I must mention this one for this reason: this is probably the most prevalent male caricature in Christian science fiction and fantasy. My definition, from

At this point, though, I do think the word icon can describe these kinds of stereotypes, mainly because of how evangelicals treat a supposed human who embodies these traits. Of course icons, by themselves, are not evil. (I have a few on my desktop. Rim shot!) The Proverbs 31 Womanâ˘, as mentioned

At this point, though, I do think the word icon can describe these kinds of stereotypes, mainly because of how evangelicals treat a supposed human who embodies these traits. Of course icons, by themselves, are not evil. (I have a few on my desktop. Rim shot!) The Proverbs 31 Womanâ˘, as mentioned