From the Travel Guide:

From the Travel Guide:

For those unaccustomed to venturing beyond their own backyards, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz provides a pleasant, sedate introduction to the land âsomewhere over the rainbowâ that is easy on both the travelerâs pocketbook and heart rate. No fear of the usual whirlwind tour of Oz on this planâŠtravelers will experience the exotic locales and peoples at a leisurely pace and from a safe distance.

Your tour guide, Miss Dorothy Gale, is a no-nonsense Kansas farm girl whose honesty and politeness will charm you and smooth over any minor bumps you might encounter during your trip along the Yellow Brick Road. Youâll see all the popular tourist attractions: Munchkinland, the Poppy Fields, Emerald City, the Witchâs Castle, and some lesser-known spots like the Dainty China Land and Hammerhead Hills.

Here’s a summary of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, for anyone who might be unfamiliar. Lots of spoilers. I recommend reading the story yourself because it’s the original, it serves as the baseline for this series, it’s free at Project Gutenberg, and it’s a quick read, maybe two hours total. Some folks may be more familiar with the MGM movie version, which we’ll take up next week.

————————————————–

Dorothy Gale lives on a farm in the gray, featureless prairies of Kansas with her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em. Itâs not an exciting life, but Dorothy is content, so long as sheâs got her little dog Toto to keep her company. One day, a tornado sweeps across the farm, carrying the farmhouse away, along with Dorothy and Toto, who didnât make it to the storm cellar and took shelter under a bed.

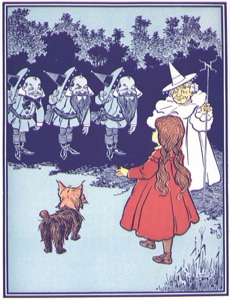

Theyâre whirled across the sky to the faraway land of Oz, where the farmhouse lands like a laser-guided bomb on the Wicked Witch of the East and among the Munchkins, who are a little smaller than average humans and favor the color blue in their clothing and architecture. They welcome Dorothy joyfully as their liberator, but she’s a well-grounded American girl unimpressed by flattery from strange foreigners, so she brushes off the compliments and inquires about how she might return home. A little old lady identifying herself as the Witch of the North directs Dorothy to the City of Emeralds and the Great Wizard therein, who might be able to help. She also advises Dorothy to take the silver shoes sparkling among the dusty remains of the Witch of the East because they possess some mysterious charm, properties unknown. Â The Witch of the North kisses Dorothyâs forehead, leaving a mark that signifies the power of Good over Evil, and bids her farewell.

Theyâre whirled across the sky to the faraway land of Oz, where the farmhouse lands like a laser-guided bomb on the Wicked Witch of the East and among the Munchkins, who are a little smaller than average humans and favor the color blue in their clothing and architecture. They welcome Dorothy joyfully as their liberator, but she’s a well-grounded American girl unimpressed by flattery from strange foreigners, so she brushes off the compliments and inquires about how she might return home. A little old lady identifying herself as the Witch of the North directs Dorothy to the City of Emeralds and the Great Wizard therein, who might be able to help. She also advises Dorothy to take the silver shoes sparkling among the dusty remains of the Witch of the East because they possess some mysterious charm, properties unknown. Â The Witch of the North kisses Dorothyâs forehead, leaving a mark that signifies the power of Good over Evil, and bids her farewell.

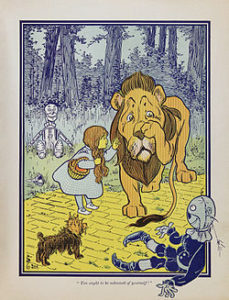

Dorothy sets off along the Yellow Brick Road which leads to the Emerald City, and she collects three odd companions along the way: a Scarecrow longing for brains, a Tin Woodsman lacking a heart, and a Lion short on courage. They encounter and overcome several obstacles before reaching the Emerald City (which is mostly white but perceived in shades of green, thanks to a universal law requiring the inhabitants and all visitors to lock themselves into green spectacles while inside the city limits), and they arrange an audience with the Wizard. He meets separately with each of them in a variety of intimidating incarnations, but promises to help Dorothy and her companions…if they agree to kill the Wicked Witch of the West.

Dorothy, being a nice Kansas girl untutored in the martial arts, has no intention of killing the Witch, but she figures thereâs nothing else for it but to travel to the Witchâs castle and convince her to stand down, or surrender, or turn over a new leaf, or something. The Witch detects their approach with her telescopic vision and, being wicked, sends wolves, crows, bees, and soldiers to kill them, but is thwarted by the ingenuity and valor of Dorothyâs companions. She finally manages to capture Dorothy and her friends with the aid of an army of winged monkeys controlled by a magic golden cap. The monkeys dismantle the Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman, then deliver Dorothy and the Lion to the Witch, who sentences them to lifelong servitude.

Dorothy, being a nice Kansas girl untutored in the martial arts, has no intention of killing the Witch, but she figures thereâs nothing else for it but to travel to the Witchâs castle and convince her to stand down, or surrender, or turn over a new leaf, or something. The Witch detects their approach with her telescopic vision and, being wicked, sends wolves, crows, bees, and soldiers to kill them, but is thwarted by the ingenuity and valor of Dorothyâs companions. She finally manages to capture Dorothy and her friends with the aid of an army of winged monkeys controlled by a magic golden cap. The monkeys dismantle the Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman, then deliver Dorothy and the Lion to the Witch, who sentences them to lifelong servitude.

The Witch’s primary interest is the silver shoes, but Dorothy wonât give them up, and the Witch is reluctant to take them by force, fearing the Mark of Goodness on Dorothyâs forehead. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on your perspective, the Witch makes a clumsy attempt to steal the shoes and manages to grab one of them, which pushes Dorothyâs patience past its breaking point. Our heroine lashes out with the time-honored weapon of the domestic servant, a full mop bucket, and the Witch, badly dessicated from her many years of wickedness, dissolves like a puff pastry left out in the rain. The locals hail Dorothy as their liberator and reassemble the Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman. Dorothy and her friends head back to the Emerald City with the flying-monkey-controlling golden cap. They lose their way, and they call on the winged monkeys to carry them to the Wizard.

The Wizard, manifesting this time as a solemn, disembodied voice, refuses to honor his promise. The lion roars in protest, and Toto scurries away, knocking over a screen in the corner of the Wizardâs throne room, which reveals a nondescript little man whoâs been the ventriloquist and puppeteer behind the Wizardâs persona all along. He confesses heâs nothing more than a carnival humbug from Omaha who arrived in Oz via a wayward balloon, which so impressed the gullible residents that they named him Wizard and installed him in the Emerald City as their ruler. Heâs been living in fear of discovery (and the witches) for so long, his exposure is something of a relief. He fulfills the petitions of Dorothyâs companions via a little more flim-flammery, which seems to be the most effective sort of magic in Oz. The Scarecrow gets a scoop of brain, er, bran (it sounds enough alike to satisfy the Scarecrow) poured into his flour-sack head, along with a handful of pins and needles so everyone can see heâs sharp. The Tin Woodsman gets a heart—itâs made of cloth, but a heartâs a heart, and thatâs sufficient to allow the Woodsman to fully express his feelings. Hey, it worked for Raggedy Ann. The Lion gets a dose of liquid courage, presumably left over from the carnival, and he’s ready to rock and roar.

Finally, the Wizard offers Dorothy a ride home in his balloon, which will require her prairie seamstress-ship and a little elbow-grease to reconstruct. The Wizard declares the branny, er, brainy Scarecrow the new ruler of Emerald City and launches the balloon, but Dorothy misses her ride as sheâs trying to corral Toto, and it seems all is lost. The denizens of Emerald City tell her to seek out Glinda, the Good Witch of the South, who might be able to conjure a way back to Kansas.

After a long journey southward through a forest of hostile trees and a bizarre land made entirely of fine china, Dorothy and friends reach the land of the Quadlings, who are similar to the Munchkins but prefer red things. Dorothy finds Glinda and learns that the silver shoes have the power to take her home at her wish. Dorothy gives Glinda the golden cap (so the Good Witch can order the flying monkeys to return Dorothyâs companions to their proper homes), makes her wish, and is whisked back to Kansas for a joyous reunion with her aunt and uncle, who have rebuilt the farm and house in her absence.

————————————————–

Of the four journeys to Oz weâll consider here, this one is the most straightforward and unadorned. L. Frank Baum intended The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to be a modern and distinctively American fairy tale, as he notes in the introduction, âin which the wonderment and joy are retainedâ from the old European fairy tales, âand the heartaches and nightmares are left out.â Thatâs a pretty good summary, circa 1900, and it might reflect the sentiment of a nation of immigrants who believed, or perhaps were still praying, that they’d left the monsters of the old country far behind them. The characters are very simple, the plot is linear, and thereâs never a strong sense of danger anywhere along the way. Weâre treated to a series of encounters along Dorothyâs journey from Kansas to Oz and back again. Dorothy meets something strange and befriends it or ponders it for a while, or she runs into an obstacle and quickly overcomes it—then itâs on to the next event. Oz is depicted as a real place, not an illusion or dreamland, and Dorothy will return there in stories yet to come.

Though Baum peppers his novel with some very creative and often phantasmagorical elements, his descriptions of Oz, on the whole, seem rather bland to me. Perhaps I’ve become accustomed to a more modern style of storytelling that relies less on the reader’s imagination to fill in detail. The first edition included a host of  delightful illustrations by W.W. Denslow (a couple are included in this post), and early reviews credited them with as much impact as the text in telling the story. There is a synergy that can emerge when pictures and words are used in combination, and some stories seem to demand it. I think this may be one of them.

Dorothy is a nice, ordinary everygirl who, while suitably impressed by the odd world she tumbles into, doesnât prefer it to life on her Kansas farm. She doesnât like Oz very much, and she worries her aunt will have to purchase expensive mourning clothes if she doesnât find a way home soon. Every problem she encounters is quickly resolved with the help of her friends and facilitated by Dorothyâs patience, optimism, pluck, and kindness. She loses her temper twiceâwhen the Lion frightens Toto at their first meeting (earning the shaggy bully a firm slap), and when the Witch steals her shoe. Thereâs no deeper destiny, motivation, or guidance, divine or otherwise, directing her beyond her desire to return home. She’s not exiled royalty, or a juvenile messiah riding the rails of prophecy. She’s simply a lost child with common sense and good manners.

Dorothy is a nice, ordinary everygirl who, while suitably impressed by the odd world she tumbles into, doesnât prefer it to life on her Kansas farm. She doesnât like Oz very much, and she worries her aunt will have to purchase expensive mourning clothes if she doesnât find a way home soon. Every problem she encounters is quickly resolved with the help of her friends and facilitated by Dorothyâs patience, optimism, pluck, and kindness. She loses her temper twiceâwhen the Lion frightens Toto at their first meeting (earning the shaggy bully a firm slap), and when the Witch steals her shoe. Thereâs no deeper destiny, motivation, or guidance, divine or otherwise, directing her beyond her desire to return home. She’s not exiled royalty, or a juvenile messiah riding the rails of prophecy. She’s simply a lost child with common sense and good manners.

The contradiction of the self-perceived shortcomings of Dorothyâs friends (theyâre the only ones in Oz unaware they have plenty of brains, heart, and courage) is obvious, yet itâs not delivered explicitly as a moral of the story but rather left as an idea for readers and listeners to connect on their own or discover via 1970’s pop music.

Good and evil are presented in direct opposition, even to the point of being on opposing geographic axes (North/South Good Witches, East/West Bad Witches), though some have bristled over the years at the inference that a witch could be anything but evil by definition, fairy tale or no. It’s stated more than once that “Good is more powerful than Evil,”—yes, they’re almost always capitalized in this story—and the Kiss of Good on Dorothy’s forehead wards off mischief at several key points. Evil, on the other hand, relentlessly sucks all the moisture out of the Wicked Witches’ bodies, turning them into dried-out husks.

That’s what’s known in the trade as an apt metaphor.

Thereâs very little magic on display in this story of Oz, and itâs almost exclusively linked to objects with an intrinsic power, like the silver shoes and the golden cap—or the animated Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman. The Wizard’s flim-flam effectively simulates magic in Oz, even intimidating the genuine magic users, though the Wizard cowers in fear of the day he might be revealed as an impostor.

Finally, and I hate to end on a low note, this isn’t a work of Christian fiction, though it does espouse a very simple and generic morality that might contain a faint echo of Christian sentiment. L. Frank Baum grew up a Methodist, then moved to the Episcopal Church later in life, mostly because it offered a venue for his theatrical ambitions. He abandoned Christianity altogether in 1897 for Theosophy, a melange of oriental mysticism and occultism emphasizing the brotherhood of mankind, studies in comparative religion, and paranormal research.

Finally, and I hate to end on a low note, this isn’t a work of Christian fiction, though it does espouse a very simple and generic morality that might contain a faint echo of Christian sentiment. L. Frank Baum grew up a Methodist, then moved to the Episcopal Church later in life, mostly because it offered a venue for his theatrical ambitions. He abandoned Christianity altogether in 1897 for Theosophy, a melange of oriental mysticism and occultism emphasizing the brotherhood of mankind, studies in comparative religion, and paranormal research.

His views on race were clearly prejudiced, though sadly common in his day. Perhaps the most disturbing of these was his advocacy for the genocide of Native Americans in the wake of the 1890s Ghost Dance movement and Wounded Knee Massacre. This fact might be enough to induce some readers to avoid his stories altogether, and anything connected to them. It certainly took me by surprise, but once I knew about it, I couldn’t ignore it or pretend it wasn’t there. It was as if I’d discovered Joseph Goebbels had penned Heidi.

However, we see none of Baum’s racial prejudice or unorthodox religious beliefs reflected in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and the story is beloved by both Christian and secular readers. We’ve often discussed here at SF whether and how the faith and values of a Christian author might shine through a story that isn’t explicitly Christian. Here’s an example of a story where we might ask a similar question: Can we sequester the writing of a non-Christian author from a personal worldview that is immoral and offensive? Or, to put it another way, can we love a story and shun its writer? How far can we go? What do you think?

Next week, assuming we have any readers left, I’ll talk about the different approach to Oz taken in the MGM film, The Wizard of Oz.

Travel always creates new stories, but especially thanks to fiction writersâ conferences. And I donât only mean coming home with new ideas for new novels (though this also happens).

Travel always creates new stories, but especially thanks to fiction writersâ conferences. And I donât only mean coming home with new ideas for new novels (though this also happens).

Both recent episodes of series 7a touched on themes of evil, vengeance, and forgiveness.

Both recent episodes of series 7a touched on themes of evil, vengeance, and forgiveness.

Itâs been said that the most compelling element of fiction is its ability to evoke strong emotion. But how do we do that? How do we infuse our writing with enough believable story to wrangle that response from readers? Iâm personally learning one particular aspect of this right now, and it cuts me to the heart, but it also enriches me.

Itâs been said that the most compelling element of fiction is its ability to evoke strong emotion. But how do we do that? How do we infuse our writing with enough believable story to wrangle that response from readers? Iâm personally learning one particular aspect of this right now, and it cuts me to the heart, but it also enriches me.