My walk across campus seemed unusually quiet that morning. There was a reason for that, and it had everything to do with where I was going. The event was scheduled to start at 10:30 am. It was a quarter after, but already I could hear muted cheers from Anderson Arena ahead of me. That wasnât uncommon for Anderson. It was BGSUâs basketball stadium, after all.

The flock of law enforcement officials that protected the building was unusual, though. This was no ordinary sporting event.

âIâm really late,â I thought, frowning. âMaybe I shouldâve skipped class.â

âIâm really late,â I thought, frowning. âMaybe I shouldâve skipped class.â

I rarely did, though. Almost never. The first time I had, in fact, was earlier that same weekâto get tickets for the event. I had to wait outside for hours.

Thanks to a Logic professor who refused to cancel class, though, my ticket might be almost worthless.

âWe have a test every Wednesday,â heâd said. âThis week will be no different. If you study, youâll finish in time to attend the speechâŠfor those that want to.â

I didnât think much of his attention to the schedule then, aside from the inconvenience. In hindsight, though, I wondered if he hadnât had ulterior motives.

For those that want toâŠ

I reached the Anderson entrance and showed the police officer what I was carrying: A pocket camera and a mini-cassette recorder. âOkay to take them in?â I asked.

He answered with a âSure!â and waved me on ahead. I was happy for a moment.

I reached the interior of the stadium. They had the arena configured in a U, with one end of the court set up as a podium, and seats on the floor in front of that. I entered from the opposite end, where the stands were still extended. The place was packed, and extremely loud.

I skimmed the section nearest me. Not a single opening anywhere.

There were a handful of people in a similar position. Stragglers that, for whatever reason, had to come late. âI really shouldâve skipped class.â

But it really wouldâve hurt my grade.

I walked aimlessly, just taking it all in. There were lots of political signs, lots of students.

A few of those nearest me were dressed in suits. A little odd. One of them approached me and a fellow straggler, with a sign in his hand. âYou guys need seats?â he asked.

We both nodded.

He held up his sign. âIf you donât mind holding a sign, Iâll get you seats.â

The suit was wearing a pin that identified him as being with a college political party. The one organizing the event.

I shrugged. Guess I can trust him. Though I hope it doesnât mean Iâm joining anythingâŠ

The suit led us straight to a section of seats near one of the locker-room entrances, the place where the team would normally enter from. It wasnât front row, but it was closer than I was expecting. A lot better than standing at the back.

I was grateful. Both to the suit, and to God. It was a gift, not having to stand. Being able to see.

A few moments later, we heard the sound of a helicopter descending. The crowdâs rowdiness increased. The excitement. My neighbor waved his sign.

It wasnât obvious where the speaker would enter from. I assumed it would be up near the front somewhere. Near the podium.

The people to my left, those closest the locker-room, began to move toward that entrance. I glanced at my new friend, and with a mutual shrug, we shuffled that way too. We took positions right next to the railing that overlooked the entrance. We kept looking forward, though. Toward the podium.

Then there was movement in the entrance below us. I glanced down and saw police officers, along with men wearing dark suits and sunglasses. Things in their ear.  The crowd got more excited. Then I sawâŠ

Ronald Reagan. He was right there, below me. I was so startled, I didnât even stick out a hand. I just watched as he smiled and shook the hands of those around me.

Ronald Reagan. He was right there, below me. I was so startled, I didnât even stick out a hand. I just watched as he smiled and shook the hands of those around me.

The president. Right there!

I couldnât help but smile.

And I came in late.

A Biblically informed political outlook?

Democrats that know me probably think me a diehard Republican, but Iâm really not. To me, politics extend directly from oneâs morality, from their core beliefs. I have the maturity to realize that there are honorable and dishonorable people in both parties. That both are capable of good or bad behavior, and that for some things, reasonable people can disagree.

If pressed, Iâd most likely call myself a conservative. But in actuality, Iâm an issues person. I think the Bible has given us clear precepts for beliefs and actions, and by definition those precepts have to affect how we view issuesâand as a consequenceâdetermine the candidates we support.

For instance, abortion is an important issue for me. That derives directly from the Biblical precept that life was originally designed by God (Genesis 1:27), that the process of life is still maintained by God (Psalms 139:13), and that he has a vested interest in each and every person (Jeremiah 29:11-13). So, by applying precept to issue, I would always error in favor of life.

That application of biblical precept extends to what candidates I vote for. I think how someone defines life, defines them. If they see innocent life as having been given by God, and therefore in need of protection, then I can be certain that in other, less important issues, they will be more likely to make the right decision.

Why? Because there is a moral framework in place. If a candidate is pro-life, I know that he or she believes inâor at least respects the concept ofâGod, and therefore doesnât think of himself (man) as the determiner of all truth. That also means that he or she views rights as having come from God, not from government, just like the framers of our Constitution declared.

We hold these truths to be self-evidentâŠ

If the value of life is negotiable, than anything is negotiable.

So, issues from precepts, morality fuels politics, and politics is all about earthly governance.

Politics in speculative stories?

Politics are a necessity in speculative stories. Whether it is charting the demise of the Dark Lord Sauron, or chronicling the rise of a Messiah King in Dune, there is always a political aspect to the worlds we create. Humans operate within the bounds of societies, and societies always have a form of governance. That governance may be in the shadows, but it is always presentâeven in the context of a small village hidden in a forest somewhere, even in total anarchy.

Wherever a group exists, there is always a jockeying for position, or a push for autonomy. People need leaders, and some people just need to lead. Epic stories arise directly from political situations: A King trying to regain his kingdom, a slave trying to achieve freedom, and empire that has to fall.

So since there are always politics in stories, then the direct interjection of personal politics into stories should be okay, right?

Well, no, actually. In fact, it might be a huge mistake.

Wait. What? You just said all stories have politics. So why canât I talk politics?

I said all stories have politics, that doesnât mean they are soap boxes for author bloviating.

Click for the complete DarkTrench Saga science-fiction trilogy.

Just like with voting, storyshould be about precepts and issues. Â Donât think about right versus left, think good versus evil. Freedom versus slavery.

The DarkTrench Saga is, in many ways, controlled by political questions: What if the world was under sharia law? What if those seeking an Islamic caliphate achieved their goal on a global scale?

Yet my books are primarily driven by issues and precepts: Are all beliefs the same? What distinguishes Christianity from other belief systems? Where is God when it seems all hope is lost?

Such questions transcend the current political climate, whatever it is. (Though they certainly could be brought to the surface by it.) They arenât right versus left questions. They are human questions.

Too much rhetoric in a book not only makes it preachy, it diminishes its potential significance. It takes it from epic, to trite. From transcendent, to temporary.

We all should seek lasting significance.

Politics in an authorâs profile?

Should an author share his political leanings publicly? What face does he present to the world? Is he activist, or political man of mystery?

Iâll admit, it is a sticky wicket. On the one hand, authors are all about beliefs and ideas. We write because we are moved, and we write to inform. Our souls are split open and displayed for all to see. So can we really hide anything?

It is all about nuance, my friend. Nuance and respect.

I try to keep political discussion to a minimumâat least on my author-specific outlets. Given the subject matter of my books, of course, it is difficult. Many of the decisions being made today, politically, appear to be tipping the scale either towards freedom, or away from it. Plus, I think people who have read my novels expect some discussion on beliefs, world events, and the uniqueness of the gospel.

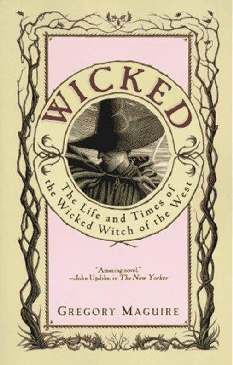

On the other hand, Iâve seen authors (and entertainers) abuse their platform. I know of a fairly famous writer, in fact, who routinely uses one of the social networks as a place to spout liberal pomposity. In the times Iâve tried to engage him, or even offered an opposing opinion, I have been belittled or attacked. Furthermore, when Iâve pointed his demeanor out, Iâve gotten little to indicate that he even sees it as a problem. It is a problem, though.

Now, Iâm sure in his mind he feels heâs educating people, so his behavior is justified.

Wrong! First rule of public discourse: Donât assume the other guy is a buffoon! In our polarized society, there is no better way to lose friendsâor as an authorâcut your potential book sales in half. Much better to let your beliefs play out naturally in your stories. Yes, there will be people who donât agree, some will be deeply offended even, but youâre writing fiction. Youâre dissecting the great âWhat if?â

Not shouting on Facebook at someone youâve never really met.

More than anything, though, be respectful of others and their opinions. They might be wrong, but they are still Godâs special creation, and should be treated that way.

Plus thereâs always a possibility that you are wrong too.

Our God is big. It is okay to be wrong once and awhile.

And as my opening story shows, it is certainly okay to be late.

(Next week, Sunday, Oct. 14: The Dark Man and Königâs Fire author Marc Schooley offers his own view of politics and social policies in fantastic stories.)

As I see it, fiction contains two components: content, or story, and the means by which the author delivers that content–the writing itself. In a comment last week Austin Gunderson referred to these two aspects of fiction as the bones and skin. I like that analogy.

As I see it, fiction contains two components: content, or story, and the means by which the author delivers that content–the writing itself. In a comment last week Austin Gunderson referred to these two aspects of fiction as the bones and skin. I like that analogy.

It is the Christian church that has largely promulgated Christian Nation Mythology. I have spent a good portion of my word count thus far criticizing it, because it is this myth that has enticed vast portions of the church to entangle itself in politics under the false premise that thereby the church may legislate America into virtue. Immeasurable resources have been donated by Christians to this cause: immense stores of time, talent, and treasure.

It is the Christian church that has largely promulgated Christian Nation Mythology. I have spent a good portion of my word count thus far criticizing it, because it is this myth that has enticed vast portions of the church to entangle itself in politics under the false premise that thereby the church may legislate America into virtue. Immeasurable resources have been donated by Christians to this cause: immense stores of time, talent, and treasure.

Roughly, this translates to my fiction as follows. It can be seen in

Roughly, this translates to my fiction as follows. It can be seen in

Oddly, all of my 40 or so books have been published in the Christian market. Why didnât I have a longer list of Christian authors? Donât get me wrong. Iâve had read a bunch of Christian titles and still do, but when asked my favorites, I defaulted to the secular end of the spectrum. This demanded some inner noodling.

Oddly, all of my 40 or so books have been published in the Christian market. Why didnât I have a longer list of Christian authors? Donât get me wrong. Iâve had read a bunch of Christian titles and still do, but when asked my favorites, I defaulted to the secular end of the spectrum. This demanded some inner noodling.

Ronald Reagan. He was right there, below me. I was so startled, I didnât even stick out a hand. I just watched as he smiled and shook the hands of those around me.

Ronald Reagan. He was right there, below me. I was so startled, I didnât even stick out a hand. I just watched as he smiled and shook the hands of those around me.

So if preach-to-the-choir fiction is what you want to write, you go right ahead and connect with one of those fine publishers. I write to be read by as many folks as I can appeal to. Niche markets are not the way to go for that, but I already knew that. I just didnât know that Christian publishing was a niche market until I landed in the middle of it.

So if preach-to-the-choir fiction is what you want to write, you go right ahead and connect with one of those fine publishers. I write to be read by as many folks as I can appeal to. Niche markets are not the way to go for that, but I already knew that. I just didnât know that Christian publishing was a niche market until I landed in the middle of it.